VOL. 40 | NO. 30 | Friday, July 22, 2016

Big names, big stories: Details of Exit/In lore lost to time

By Tim Ghianni

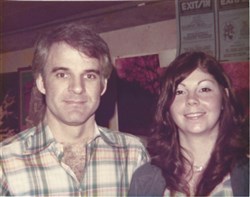

All who were there seem to agree that Steve Martin took his Exit/In audience down the street for burgers, though there is little agreement on which restaurant or whether burgers were purchased.

-- SubmittedSo, did you ever hear the story of Jimmy Buffett stepping through a small, open door, surprising the occupants, then successfully auditioning to play at a new club with a capacity of 90 people?

How about the one in which a young comic named Steve Martin led the crowd out the door and down the street and bought them hamburgers?

Well, let’s get to Buffett first. First of all, he wasn’t there singing with wink-and-nudge abandon songs about slushy drinks, carnal adventures or pirates. He didn’t even wear a flowered shirt.

It’s a true story from the very start of Nashville’s Exit/In, 45 years ago.

Buffett, looking like any typical Nashville songwriter (because that’s what he was), walked in the door off Elliston Place one day in the very early 1970s and smiled at the two 24-year-old dreamers – Brugh Reynolds and Owsley Manier – who were putting the finishing touches on their 90-seat nightclub.

“Jimmy Buffett came in. We were kind of finishing the place up, the first incarnation,” says Manier, remembering that initial encounter with a guy who would later adopt the Parrothead-and-hung-over-pirate shtick that has made him untold millions.

The door of the old building onto Elliston Place was only opened for ventilation during the construction. Soon it would be sealed and the way in would be to go down a few stairs behind the building, using the exit to literally get in to hear music or nurse beers. Exit/In … get it?

“He said he wanted to audition,” says Manier. “I told him to go ahead. Then we hired him.”

That was 1971, and Buffett became the first performer at the tiny “listening room” Reynolds and Manier had dreamed up, a place where the audience was “shushed” before “shushing” became cool.

“We were very idealistic about it,” Manier adds. “We wanted people to remain silent. We made an announcement: ‘Refrain from talking,’ and we would throw people out if they wouldn’t be quiet.”

It was the birth of a tradition and a club that has evolved over the years from listening room roots to a storied rock barn reality.

Exit/In developed a reputation as a “must” stop for those early wandering troubadours: lovable losers, no-account boozers, honky-tonk heroes. And comics.

That’s where Steve Martin comes in … and leaves, taking the crowd with him for hamburgers, according to varied accounts of that incident.

There are many versions of this story, depending on who’s telling it. Current co-owner Chris Cobb has heard most of them.

“In separate versions, some people say he took them to Friday’s (then a neighbor of the club). Other people say it was Krystal. I was talking to a guy two weeks ago who said he was there and it was Krystal. ‘I was there. He bought me a burger,’ the guy said.

“I think what we know (for sure) is that he was there and he takes everyone somewhere that made some kind of burger,” Cobb says with a laugh.

Perhaps then it’s best to just use Martin’s version from pages 164-165 of his book “Born Standing Up:’’

“It (Exit/In) was a low-ceilinged box painted black inside, with two noisy smoke eaters hanging from the ceiling, to no avail. The dense secondhand smoke was being inhaled and exhaled, making it thirdhand and fourthhand smoke….

The room seated about two-hundred and fifty, and the place was oversold, riotous and packed tight, which verified a growing belief of mine about comedy: The more physically uncomfortable the crowd, the bigger the laughs…. (He began taking crowds outside to end the show and make room for the second set.)

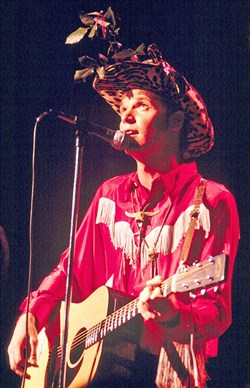

Jason Ringenberg of Jason and the Scorchers playing the Exit In in 1983.

-- Submitted Photo By Alan Mayor“One night at the Exit/In, I took the crowd down the street to a McDonald’s and ordered three hundred hamburgers to go, then quickly changed it to one bag of fries.’’

Such unexpected events became the norm for Martin’s crowd, and he began to realize that his comedy really had no boundaries:

“Even though I had done the act hundreds of times, it became new to me this hot, muggy week in Nashville. The disparate elements I’d begun with ten years before had become unified; my road experience had made me tough as steel, and I had total command of my material. But most important, I felt really, really funny….’’

Musician/nice guy Bill Lloyd is still sorry he missed that night, but he did see the wild-and-crazy legend-in-the-making at the club. “I wasn’t there the time he took everybody to Krystal’s. He acted like he was going to take us all out. Then he said ‘No, I did that last time.’”

There are many stories about the club. And then there are the half-truths and truths. But Buffett wasn’t the only young artist who got his first boost to stardom on Elliston Place.

It wasn’t that long after Buffett christened the place that “John Hiatt came in,” says Manier, remembering the sight of the skinny, 18-year-old with a guitar. And he kept coming in and performing even as the club made its transformation from small listening room to larger listening room (they added the building next door as an extension of the club in its first year) to a mini-arena-like place with more seats than bodies to fill them and then to the standing-room-only rock hall where acts like Jason & The Scorchers, R.E.M. and The Ramones would play.

Manier explains his original dream was initiated by visits to a similar club “called The Bottom of the Barrel, I think, in Underground Atlanta.”

He became a frequent visitor when he was on leave from Fort Benning where he was undergoing basic training for National Guard duty in the early 1970s.

“It was this listening room in a little club. They had the early Allman Brothers, and mostly folk stuff. You could hear a pin drop, and I was really impressed by that.”

Something clicked inside Manier’s brain, and when he was back in Nashville, he met up with Reynolds at Bishop’s Pub. “I said ‘I saw this place in Atlanta. Why don’t we look at it? Why don’t we do it?’”

They did both. “We didn’t have any money. We both borrowed a little bit of money on our life insurance policies to buy it,” Manier adds.

“Nothing like that had existed prior. We were seat-of-our-pants learners. It really was all about doing something cool. It was all about the music.

“I don’t know how people started hearing about it. People talked, said it was a cool place to play.”

Nine months into its existence, the club expanded into a former H.G. Hill Grocery store next door, could seat about 200 people and the word continued to spread nationwide, through the music community.

“We had a vision for a place with a stage where acts and small groups could play and have a venue for local talent of which we knew Nashville was full, and it wasn’t just county. In fact, we resisted anything that resembled a country act for the first couple years,” says Reynolds.

“Back then there was no nightlife, no going out to hear music all the time like we have now. The only live music was in Printers’ Alley or on The Grand Ole Opry, two widely divergent experiences.”

“We wanted people to behave like they would in a movie theater (in fact, they did host art house films when they had no music to offer.)

“So we unwittingly became a cog in the music industry and learned that groups toured around clubs like this,” he adds, noting that the Exit/In – the funky little place where you came in the back and the acts dressed in an out-building to the rear of the property – became a major touring stop back when labels sent acts out on tour behind a new album.

“Places you could compare it to were the Bottom Line in New York or what was that place in L.A.? The Troubadour,” Reynolds adds.

The eventual big-business growth of this club into what it is today – Nashville’s best-known rock hall – is chronicled elsewhere in this package of stories.

But Reynolds, Manier and Liz Thiels (who became a partner early on) created an indelible mark on Music City’s live scene and actually opened doors – both front doors and back doors – for a city that now has a seemingly endless number of listening rooms.

“Our goal was to create an environment. … We were going to make the place so cool that they’d come even if a turtle was playing,” says Manier, laughing at that naivete.

“But the reality was that we had some incredible people there, and no one was there [listening].” Crowds were slow catching on.

They began booking acts like B.B King, Odetta, Waylon Jennings. Heck, they even had Billy “The Piano Man” Joel play there for $1,500 back in the days when labels subsidized performers’ national tours to promote recently released albums. (That was when vinyl LPs were king, long before they became a collectible and sometimes pricey oddity in these compressed, digital years).

“One thing that was interesting to me is that because in those days we played a lot of black artists, on any given night the place was 80 percent black people,” Manier explains, illustrating how inadvertently the Exit/In was breaking down societal barriers even while the dream materialized.

Thiels, now retired after a career in public relations and as an executive with the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, became in charge of publicity and carting the artists around town for radio interviews.

There were live broadcasts, WKDA did a rock night on Wednesday, and WPLN broadcast the Sunday night jazz – all fed to the stations via old-fashioned telephone lines.

Not always were they successful, though.

“The record labels and the artists were just thrilled to be broadcast, we never called for permissions,” Thiels says.

That caused one performance headache when Rahsaan Roland Kirk – multi-instrumental jazz player, best known for his tenor sax – came to perform. “He found out we were going to broadcast his show live (and he became angry) and he played a really short set and said ‘That’s all for a suck-ass rock station,” she recalls, with a laugh.

While the owners were losing money, they were happy to see their club’s stature increase nationally.

In fact, Thiels illustrates that occasionally the glowing reputation – and high regard from national music magazines – sort of outpaced the reputation locally.

“Dizzy Gillespie played there, and nobody came,” she says, awe and disappointment still flavoring her words all these decades later.

“It was Dizzy Gillespie (the legendary jazz trumpet player), and we could not figure out why the jazz people didn’t come to see Dizzy Gillespie.

“I asked a jazz guy ‘Why didn’t you come?’ And he told me he ‘didn’t think it would be him.’”

Still none of those early owners has many regrets, and would do it again.

“Outside of losing a bunch of money, sure,” notes Manier, when asked if he viewed the club as a success despite the fact the original owners piloted it into bankruptcy. “People love that place, and I can’t tell you how many people met their wives there … all of them.”

The national acclaim was not reflected in ticket sales. “We were struggling to survive. There were times when, as the owners… the wait staff and the bartenders would make more money than us.

“Waitresses could make $200 or $250 a night, and that was a lot of money back then,” but he wouldn’t change it. “It was a place of magical musical happenings and the interaction between the musicians and the audience was energizing,” Manier says.

“We didn’t go into it to make money,” says Reynolds. “Unfortunately that’s not a good way to go into a business venture, but we did what we wanted to do.

“You had to be there to know what it was,” he says. “You had to be there.”

Of course, the club had its ups and downs, but it did make it through its infancy to become what essentially was a cavernous concert hall, the perfect venue for rock bands.

Current co-owner Cobb is proud of the club and its history.

“I think it’s a very special place and a very special thing, and I think that, as a city and as a music community, Nashville is so fortunate to have the Exit/In,” he says.

“I’m sure most of us take the Exit/In for granted. But it’s rare. There’s not a lot of places that have a 45-year-old rock club.”