VOL. 40 | NO. 30 | Friday, July 22, 2016

Exit/In: Nashville’s rock temple still standing

By Tim Ghianni

Warner Hodges, among the world’s best rock guitarists and a guy who helped give Jason & The Scorchers their ear-searing cow-punk sound, gets excited when Exit/In and its glorious history gets introduced into a leisurely, summer afternoon conversation.

“It was the mecca of all meccas,” he says, referring to the club that evolved from its beginnings as a tiny listening room for storytellers and acoustic guitars into one of the nation’s best-known rock ’n’ roll clubs.

Now celebrating 45 years of music on Elliston Place, Exit/In’s identity at birth was radically different than that of the large rock barn where Hodges says “everyone wanted to play if they couldn’t play Municipal Auditorium.”

By the early ’80s, the club had made that transition, and there were competing rock clubs around Music City. But playing Exit/In was the signal that they’d made it.

“Those days, what you were hoping to graduate to was the Exit/In,” says Hodges.

“It was the club,” says Tommy Womack, who with his pals in Government Cheese did make the big step to the Exit/In.

The Cheese knew about the club’s legend even though they were headquartered up Interstate 65 in Bowling Green, Kentucky.

“We were the red-headed stepchild as far as the Nashville music scene,” he says. “Back then we had the Cannery and the Exit/In, and if you couldn’t draw enough of a crowd to play the Exit/In, you’d play Elliston Square,” says Womack, talking of the band’s fulltime 1985-92 incarnation.

“We had fun playing Elliston Square, but we wanted to play for more people and make more money. The Cannery, we played there and had a ball.

“But the Exit/In was king. Everybody wanted to play the Exit/In. If you packed it, there was a nice piece of change,” Womack recalls.

He said his band did end up opening there for Jason & The Scorchers “a couple of times.”

Club co-owner Chris Cobb sits backstage at Exit/In.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerThe Scorchers still exist, although they play only a fistful of dates a year – “money has to fall from the sky,” Hodges says. Their money now comes from individual projects, but back in the 1980s and 1990s they were an “almost-big-time” cow-punk band, flirting with an international following.

And while they toured the world – and still do in their other projects – and they retain the spot atop the Nashville rock history pecking order.

“I first played the Exit/In in ’76 with The Press, one of those bands that I was with for just a summer. I was still in high school,” says Hodges, who grew up in Nashville, the son of aspiring country artists.

But the Scorchers, birthed in 1981 “did a lot of shows at the Exit/In,” notes Hodges. “And it was a big Nashville homecoming stop for us if we were coming back to Nashville,” he says. “We did the Cannery some, but mostly it was the Exit/In.”

The aura of that club was enhanced by the big-names that played there. “I saw The Police with 12 other people,” says Hodges, a nod to the fact the club took a long time to get established.

“To those of us who were actually Nashvillians and the kids out of that scene, the Exit/In was the end all to be all.

“I saw The Romantics there. REM also played there. It was where everybody wanted to play if they weren’t big enough to play Municipal Auditorium.”

Nashville rock mainstay Bill Lloyd, who teamed up with Radney Foster for the ground-breaking Foster & Lloyd, pre-cursors of what is now called the alt-country/Americana sound, says he started to go to the club when he turned 18, then the legal age for beer consumption in Nashville, while around his old Kentucky home, the age was 21.

“I’d come down from Bowling Green when I was 18,” he says during an afternoon spent fishing for vinyl at Phonoluxe used-record store on Nolensville Pike. Some of the artists he saw then included Warren Zevon, Stephen Bishop, Joan Armatrading and The Dixie Dregs. “And the hippie side of Nashville was happening with bands like Barefoot Jerry.”

His biggest night at Exit/In was at the release party for his rock record “Feeling the Elephant,” an evening that included Nanci Griffith, Pam Tillis and Radney Foster and other friends.

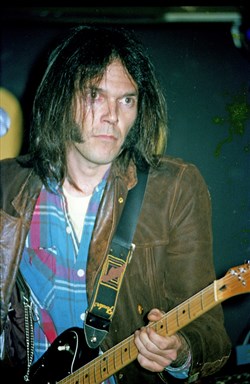

Neil Young rocking the Exit/In in April, 1977.

-- Submitted Photo By Alan Mayor“We had not only that record coming out, but the ‘Foster & Lloyd’ (the eponymous debut album of that pairing) thing had been out, as well,” he says.

That came in the mid-to-late 1980s, and the club had already made its leap to big-room rock status from an era when the then 200-person capacity listening room hosted folks like John Prine, Tony Joe White, Willie Nelson and Bobby Bare.

“I was playing in there one night, and Neil Young and Dickey Betts (Allman Brothers guitarist) and Shel (Silverstein) was all there,” says Bare, who used to wander over to the club when things were slow at his office on Music Row.

“And, hell, I got them all up there onstage with me. We were all singing, I don’t know what it was,” he says with a laugh. “Neil and Dickey played guitar. I think Shel played harmonica.”

Owsley Manier, one of the original owners, says such friendly drop-in groupings happened all the time, because so many of the city’s musicians “hung out here all the time.”

“It was cool,” he adds. “I remember Barefoot Jerry or Mac Gayden had done a show and the Allman Brothers were in town.

“Greg (Allman) came over and wanted to play with them.”

That friendly drop-in led to a jam that lasted until about 7 a.m.

“I made an announcement it was closing time,” says Manier. Anyone who remained after that announcement was locked in until the jam ended and the sun began to rise.

It even is a multi-generational place of music, as Bare and his son, rock veteran Bobby Bare Jr. (or Bare Jr.), have played there. As have the Jennings, Waylon and Shooter.

The bar near the exit (which really was the entrance of the smaller club, hence the name) was a good hangout for singers, songwriters and honky-tonk heroes. It was the kind of place where you could sit down and talk with Bare, for example, as he enjoyed a post-show libation.

“One day, me and Shel and David Allan Coe was in there in the afternoon,” recalls the elder Bare, who still possesses one of the best voices in any form of music, let alone country.

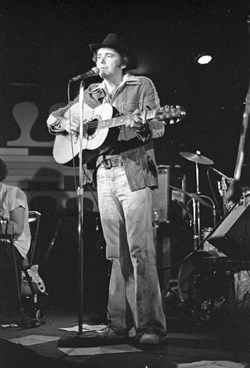

Bobby Bare playing the Exit/In in April, 1977.

-- Submitted Photo By Alan Mayor“Wasn’t anybody there but one or two people. We were just sitting there and some drunk guy came up and started jumping in Shel’s s---. I don’t know what it was, something Shel had written. The guy kept on and I figured David Allan Coe, with his history, would get up and pinch the guy’s head off. I finally got up and told the guy to get the f--- out of there.”

Bare says one of the things that made Exit/In special was, “They always had a good sound system that most of the guys wasn’t used to.”

Another regular to that early version of Exit/In was Billy Joe Shaver, who one night did his sparse, acoustic version of “Honky-Tonk Heroes” – a landmark theme album of his songs as recorded by Waylon Jennings.

Then there was Doug (Ragin’ Cajun) Kershaw, who fiddled his way among the small, round tables, amping up the audience’s enthusiasm.

Club co-founder Brugh Reynolds says that when he and Owsley Marnier designed the 200-seat listening room, it was done with the hopes that artists and audiences would mingle, as did Kershaw.

“We ran the carpet up on the stage and to the floor. The only separation from the artists was a little bit of elevation, so it was connected.”

It should be noted that Jennings’ penchant for hanging out at the Exit/In restaurant and bar helped keep the doors open.

“Waylon would go there and hang,” says Peter Cooper, a reformed journalist, music historian, musician and museum editor at the Country Music Hall of Fame.

During one of the financial crises of the early days, Jennings – on top of his game back then – did a show there to raise money to help the Exit/In pay its bills.

“He didn’t want to lose his favorite hang,” Cooper says.

Liz Thiels – who joined the ownership team a few months after Exit/In opened – says Waylon’s was an appreciated night.

And, she adds, other friends stepped forward and onto the small stage for benefits “after we started to feel this financial nightmare” that led to bankruptcy, new ownership and eventually the expansion to what remains Nashville’s favorite large rock hall.

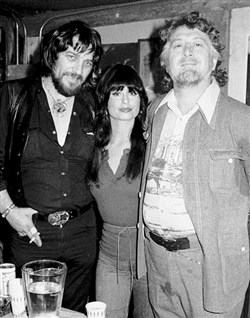

Waylon Jennings and Jesse Colter with Jack Clement at the Exit/In in 1976.

-- Submitted Photo By Alan MayorIt was after that transition that Webb Wilder – the “Last of the Full-Grown Men” – recorded his classic 1986 live album “It Came From Nashville” at the club.

Wilder, who remains active as a rockin’ wandering troubadour – “If I don’t wander, I don’t eat” – recalls that the acts he saw as an out-on-the-town Peabody College student hooked him on what then remained a listening room.

He recalls he visited the already famous club “it seems like on the very night I got here” in 1974. “It was this big-time club like nothing I ever saw. I went to the Exit/In and saw (R&B legend) Esther Phillips.

Others he saw early on included “Emmylou Harris on her first major-label tour.”

He also recalls his own venture into adulthood: “I used to try fancy drinks there. I ordered a rusty nail.” No telling how much that impressed Waylon, the best-known bar regular.

“I saw Barry Manilow there. I don’t know why I was there for that,” adds Wilder. “I think I was there because we were just a bunch of Peabody students looking for a place to go and something to do.”

Reynolds sounds baffled even today when talking about the guy who really didn’t write the songs that made the whole world sing.

“One of the more interesting bookings was Barry Manilow, back in ’75, ’76. He wanted to play the Exit/In. We didn’t really want Barry Manilow because he was the essence of pop.”

But Manilow’s camp was persistent. “Finally I told them that all we could pay was $500,” and he was told that was fine with the “Mandy” singer. He hadn’t planned on making much money. “He just wanted to play the Exit/In,” Reynolds explains.

After his Peabody experience, unrepentant rocker Wilder left Nashville for awhile. “I came back up here in ’82 and started playing as Webb Wilder and The Beatnecks,” he says.

Billy Swan and Barefoot Jerry perform on May 29, 1975.

-- Submitted“(Exit/In) had made the transition (to a big rock club) while I was gone.” His fond memories of performances he witnessed there include Jerry Lee Lewis, The Police and many other non-arena-level acts.

Historian/musician/journalist Cooper first played the Exit/In as bassist for his Spartanburg, South Carolina, chum Baker Maultsby before he was hired 14 years ago (by this writer) to work as chief music writer for The Tennessean morning newspaper.

That led to some embarrassment Cooper still feels all these years later, because he looked out and saw his favorite guitarist, Hodges, in the first row. The young man from South Carolina – who still says that Jason & the Scorchers is the best-ever rock band (Beatles and Stones fans would tell him otherwise) – laughs at himself, now. “It was then that I regretted being not very good at bass.”

Another key in the growth of Exit/In was its role in the growth of a fresher form of the Nashville Sound.

“In the late ‘90s, Billy Block moved his Western Beat show there. That was a show that featured multiple roots music artists each Wednesday night. It was broadcast on the radio and was frequented by Music Row folks,” Cooper recalls.

“That became the gathering spot for Nashville’s roots music community (into which Cooper immersed himself – but not as a bassist – after moving here),” he says. “Everybody would go to Billy’s show and then go next door to Sherlock’s Pub.

“It wouldn’t be unusual to have Lucinda Williams, Nanci Griffith, Allison Moorer, Chuck Mead, Webb Wilder, Bill Lloyd and dozens more people (including Cooper) who were central to the roots music scene.

“Billy was the ringleader, a galvanizing force for what would be called ‘Americana’ and for a few years Exit/In became alt-country ground zero.”

Cooper then puts on his historian’s cap to sum up the club and its long and sometimes winding road.

“It was always an edgy and hip kind of place,” he says. “In the 1970s, it was a real cradle to singer-songwriters. People like Guy Clark reigned supreme.”

Even though it long-ago transitioned to a big rock room, it remains “hallowed ground,” Cooper says.

“Every time I drive past the place, it’s a reminder to go out and hear music, because there are so many amazing nights that were there to be experienced in real time. They weren’t recorded or documented in any way.”

Dave Coleman, leader of roots-rock trio The Coal Men, dreamed of playing the Exit/In when he was a young man “growing up in Jamestown, up in the Plateau. There was no music scene whatsoever.”

But he’d heard about the legendary club on Elliston Place, and he thought it was the perfect place to take his music. “It was edgy enough and rock ‘n’ roll, and it was where I wanted to get to,” he says. “It was this big rock club that sounded amazing.”

He adds, with a laugh, that it was probably the first club he got thrown out of for being underage. “I wasn’t quite 21, and I went to see this Hank Williams tribute show. I was so bummed.”

That was long ago, now he and The Coal Men have played that storied venue at least 20 times, including multiple appearances on the late Block’s Wednesday night roots-rock celebrations.

“The Exit/In is just small enough and has a cozy-enough vibe. But the stage is big enough to feel like a punk-rock club,” Coleman says.

“Bands come and go. Sometimes clubs go faster, but the Exit/In gives me a little faith,” he adds.

“With Nashville changing so much now, it’s comforting to know there are always going to be great rock ‘n’ roll shows there for the bands that are coming up. And it’s on this great street called Elliston. It’s a little micro-community that really means a lot to me.”

The importance of the club and its legacy was made crystal clear in the summer of 2012, when original Jason & The Scorchers drummer Perry Baggs (or Baggz, depending on how “punk” he was feeling) died alone in his home, after decades of struggle with diabetes and with neither money nor insurance.

Hodges gets reflective when talking about Baggs, the first friend he made when his family moved to Nashville and a guy with whom he toured the world as The Scorchers earned critical acclaim and success that fell just shy of “the big time.”

The Scorchers lost a big chunk of their soul that day, and – though they all had other projects in the works – knew they wanted to reunite in an effort to pay the gentle drummer’s funeral expenses.

And, of course, a benefit concert had to be at Exit/In – site of so many Scorchers’ triumphs.

“Some of Perry’s big successes were there. Some of our biggest successes were there,” Hodges says.

“The Exit/In was kind enough to let us use the room for both shows,” he says, recalling that on the first night of the fund-raising effort, a number of local friends in other bands climbed up on the stage.

“The best drummers in Nashville came out to play with us” in tribute to the man who had kept the beat of the legendary cow-punk outfit for so long.

The second night was all-Scorchers, Hodges says, recalling a 3½-hour show that would have made Baggs’ arms sore and sparked memories of all those nights spent at the club, some of which were used on “Wildfires and Misfires,” a retrospective look at the group, including live takes, outtakes and rarities.

“We must have played there 12 or 15 times,” remembers Hodges, who is on the wall of fame both as a Scorcher and as a solo artist.

He thinks back to the beginning, and recalls how it felt when standing on that stage, 700 fans screaming, Hodges slinging his guitar, Jason flailing about and wailing, Baggs drumming, Jeff Johnson on bass.

“Here you were a little local band playing on the same stage The Police played,” he says, listing a number of other big names who he saw there in the early years.

He remembers looking down from the stage and thinking “OK. I’m doing this s---. I’m doing this stuff, not just talking about it, but doing it.”

Now, the club has evolved, booking younger acts for a younger crowd. “It’s what it should be doing, what I would expect it to do. That’s how it was in our day, too.

“We spent a lot of time there in the ‘80s. The Exit/In was where you were trying to get to.”