VOL. 40 | NO. 45 | Friday, November 4, 2016

Rigged election? Not in Davidson County

Bobby Medley, left, and Reid Lovell know this election is not rigged, at least not in Davidson County. They are in charge of ensuring the accuracy of voting machines.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerMy long-ago English professor and her electoral advice floods the front (or is that the back?) of my brain during every election cycle, even in one as bitter and nauseating as this year’s.

A political junkie and incorrigible defender of truth, justice and the American way, I recalled that advice as I pulled my car to an anonymous curb in front of an indistinguishable building near the heart of an ever-evolving/devolving Nashville (depends on your opinion).

After hitting the doorbell and voicing the secret password (in this case it was my name, which I suppose wouldn’t work for the rest of you), I enter the concrete fortress. Behind me the metal door locks securely, doubtless a precaution to keep ISIS, less-influential garden-variety terrorists and chest-thumping candidates – presidential, provincial or parochial – from bothering the two men who literally hold the elections in their hands in this warehouse filled with voting machines.

The guy who allows my entry, Bobby Medley, 51, leads me through this outpost of democracy not far from … well, I’m not supposed to say. It’s OK for journalists and cops to know, but the public generally has no idea about the contents of this concrete building, with no identifying signage.

Bobby leads me a few feet inside this jammed warehouse and points at the gray chord hanging from the back of one of a sea of identical contraptions that Tuesday will determine the fate of our United States, the world even.

His eyes fill with something resembling a mix of laughter and anger.

“Everybody’s hung up on the internet and rigging (the election),” he says, looking from the one voting machine where he stands and gazing at the even rows of machines, lined up like so many tin soldiers, extending far into the shadows of this tidy, yet cluttered, warehouse.

“That’s the only chord on these machines, and it’s just plugged in to charge the battery,” he says. “Our votes never go on the internet. Ever.

“There’s no way it can be rigged.”

Trump, of course, is not in the room, and I doubt he’d believe that message, anyway. Too busy reading Hillary’s e-mails, I’d guess.

Bobby is the most important Democrat in Davidson County. The guy who shares the warehouse duties, Reid Lovell, 61, is the most influential Republican. Both are damn nice guys. Despite their importance to us all, these men could easily get lunch at any nearby cheeseburger emporium and remain anonymous.

For the last 32 years, Bobby has been the Democrats’ voting-machine technician for the county. He has been aided for the last 11 by Reid, the GOP’s voting-machine tech. It’s an easy-going, yet politically diverse, tandem. The Felix and Oscar of the Election Commission.

“By state law, you’ve got to have a Democratic and a Republican voting-machine technician,” Bobby adds, noting that he probably got his party’s spot because of his voting history. “I’ve always voted Democrat.”

Reid, who is busy in the office making preparations for Tuesday’s vote, stoically admits he’s the Republican technician.

“But don’t hold that against me.”

Course, he too is joking in this divisive election year as the clock ticks down to when the 800 machines will be distributed around the county, where voters will decide between Hillary and Trump.

Neither man expresses a preference for one presidential candidate over the other, only allowing that they do represent the two major parties as Metro Election Commission workers.

The fact that these men are of different electoral persuasion is simply a nod to the old idea that someone could steal votes. The idea is that they balance each other out so no one can claim partisan hanky-panky swayed the election. At least not in our town. Their town.

Reid, by the way, dismisses the notion put forth by his party’s candidate that this is a rigged election.

“I’m better off not saying anything about that,” he says, with a slight chuckle, as he offers me a bottle of water. I decline.

Actually the two act as a team to maintain and deliver the appropriate machines to Metro’s 160 polling places. After the machines are used, the men oversee the repopulation of the warehouse.

They also take care of the signs warning people to wait their turns and other signs noting that any partisan activity, i.e., campaigning (or perhaps flogging the opposition?), must be done at least 100 feet from the entrance to the school, church, strip joint, fraternal lodge (are there any sororal lodges?) … well, just anyplace where folks vote.

“I think of it as much more than a job,” Reid says. “I think of it as a big public service.”

Bobby nods in agreement. “We don’t get any sleep the night before the election,” he adds.

“And Reid and I will work until the last vote is counted.

“That could be 3 in the morning after the election. It depends.”

The two affable fellows in this top-secret warehouse in a shattered – and likely soon to be filled with condos and cupcake shops – section of the city began formally setting up for Tuesday’s elections on Nov. 4 (which, to you, dear readers is either “today” or “last Friday.”)

The schedule was to put more of the machines in place on Saturday and finish up Monday so every vote can be counted – BY THEM – after the polls close.

That counting begins as soon as those little cartridges – the small boxes that poll workers insert in the machines before each voter steps to the touch screen – are brought to the Election Commission offices in the Metro Southeast building, the former Genesco Plant.

Those cartridges – Bobby calls them “activators” or “PEBs,” the latter an acronym for Personal Electronic Ballots – all contain people’s hopes and dreams (or fears … but more on that later) and are delivered by each poll’s officials to the Murfreesboro Road Election Commission offices at Election Day’s end.

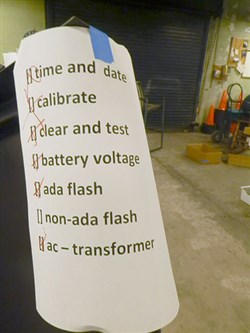

Checklists on the computers help Bobby Medley and Reid Lovell keep track of their progress in getting machines ready.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerThe voting machines themselves remain at the polling places until Bobby and Reid (like thousands of similarly inclined patriots nationwide) finish determining who is president, congressman and the like.

The first mission of the two men is to run the cartridges though a computer to assemble the results. But I like saying they will determine the winners (are there really any?) Tuesday night. “Don’t get fooled again,” is the musical advice/warning issued by my old pals in The Who.

Bobby and Reid are the folks responsible for the sanctity (I did not say “sanity”) of the election.

“We leave the voting machines in the polling places until after we finish the count,” says Bobby.

“That way if there is any problem, we can resolve it by using the votes stored in the machines.

“If one of the machines gets chucked in the river, then we still have people’s votes.”

He’s deadly serious when he uses the “chucked in the river” illustration. No, this isn’t Chicago, as most dead people don’t vote here. But all backstops are used to make sure votes get to the right place.

Beginning at 5 a.m. Wednesday, the two men and their crew from Ted R. Sanders Moving – contracted by Metro – begin loading the machines and bringing them back to this top-secret location.

“Well, it’s public record, so people can find out where we are, but there are people and businesses on this street who have no idea what goes on in here,” Bobby explains. “And we like it like that.”

That way, the men, whose full-time jobs are to maintain these machines and get them to and from the polls for every election, can do their maintenance work without interruption (well, I did interrupt, but they seemed OK with it, as I was neither rowdy nor verbally partisan.)

“We test each of these machines at least three times to make sure they are functioning properly before we take them to the polling places,” Bobby says.

Then there is the little matter of repairing the machines both before and after they stand silent sentry on something closely resembling dear old “democracy in action.”

“Sometimes we can repair them in 10 minutes – I don’t like to use the word ‘fix’ – and sometimes it takes all day,” Bobby points out.

During a tour of his quiet domain, Bobby explains that each machine has a white sticker on the floor below it, indicating its number, so he can tell the movers which ones to take where. “We have four trucks, two men to a truck.

“They can get 80 or 90 machines in each load,” he says.

Other workers distribute the red envelopes holding the pre-programmed “activators” to the appropriate polling places.

“There’s nothing in here at all except for ballot information.” Bobby shows me one envelope with two of the activator cartridges. Another with four.

Bobby Medley is only 51 and our author, Tim Ghianni, is almost 65, so Tim let the younger man scale a high wall ladder to snap a long shot of the voting machines awaiting the Nov. 8 elections.

-- Bobby Medley For The Ledger“Depending on the number of voters we expect, we try to make sure there are enough so that people don’t have to stand in line a long time.”

He notes that 200 of the machines are “ADA compliant” – meaning they are equipped with portals into which headsets can be plugged, so the visually impaired can vote by selecting from audio lists of candidates or ballot issues. These machines were added to the flotilla in 2006, so this demographic no longer would need someone accompanying them into the booth and helping them vote.

“I watched as the first sight-challenged person voted. He said it was the first time he ever voted without assistance,” Bobby adds. “It made me feel great.”

There will be at least one ADA-compliant machine in each polling place, he notes.

“We’ll have two at Howard School,” because of the sheer number of voters expected at the disjointed Metro office complex.

He says “we take pride” in making sure everyone who wants to vote is able. Of course at some polling centers, wheelchair ramps are needed – depending on the grade at the entrance. He and Reid have a bunch of those, too.

Asked if there are any special modifications for those who are in wheelchairs, he notes that the actual “face” of the machine, with its buttons and toggles, already is on a level easily reachable by those in wheelchairs.

Besides the ramps and machines, tables and appropriate signage are delivered to each polling place before the election can begin.

On the actual Election Day, Reid stays in this non-descript warehouse just in case someone needs an immediate technical solution. Bobby wanders the city’s polling places to make sure everyone is OK, democracy survives.

Then the pair goes to the old Genesco plant to wait for the PEB cartridges to be delivered. Bobby and Reid take care of the compiling the numbers that night. (Back in ancient times, when daily newspapers held the presses to get the tallies in, this was an even-more-pressing task.)

In subsequent days, to audit the election, the two compare the tallies in the machines to those from the PEBs.

So while in essence we all will know who won in the hours after the polling ends, and most news networks “call it” much earlier, it takes “five or six days to audit the election,” Bobby says.

By the way, political elections are not the only time these machines are used. Earlier in the day of my visit, the men took voting machines to and from Paragon Mills Elementary, where the students held a mock vote.

“These machines belong to the people,” Bobby adds. “We take them to churches, where they are voting on a pastor, and to universities for Student Government elections.”

As long as it doesn’t interfere with their civic duties, the machines can be used at no charge by any group of Metro Nashville citizens hosting a vote.

“If you wanted to have a vote in your church whether to have hamburgers of hotdogs at the Fourth of July picnic, we can do that,” he says. (I always vote “burgers.”)

Stepping out of the secure warehouse after spending a couple hours with these men, I think again to the presidential election and what my Iowa State University English prof – Betty Kirkham – advised me on the day of my first vote, the day our nation was picking between Richard Nixon and George McGovern.

“Vote your hopes, rather than your fears,” she said as creative-writing class dismissed for the day. For me, in 1972, that choice was simple enough.

Now, though, I nurse my ’85 Saab from the curb in front of the building where machines that record those hopes and fears are stored in near-perfect rows, ready for Bobby and Reid to do their duty to insure that we all have the opportunity to do our duty as well.

Driving off, I repeat Bobby’s final words, a quote he picked up somewhere: “The most powerful thing we own is our vote.”

Arriving home, I called the Iowa State University English Department. I was hoping for Professor Kirkham’s contact information, so I could tell her how long-lasting are her words.

“She passed a long time ago,” a soon-to-retire English department staffer tells me. (Hell, I did graduate in 1973, after all.)

It really doesn’t matter how long ago she died, because Betty Kirkham’s words have guided me through decades of presidential elections: “Vote your hopes, rather than your fears.”