VOL. 40 | NO. 37 | Friday, September 9, 2016

Photographer Steber captures fading legends on Blues Highway

“Joe Cole,” Bobo MS 1995

Retired mechanic and musician Joe Cole lived on his former employer’s farm in the same small home with no plumbing for almost 50 years. Cole, an accomplished musician who never recorded or played his music beyond Coahoma Co., preferred to spend his time gardening and working on his truck. Twice weekly Cole collected fresh water for himself and his wife from a spigot one mile away and hauled it home for cooking and bathing. Cole exemplified the resilience of African Americans in the Mississippi Delta to carve out a life and create art despite the horrific conditions under which he was forced to live.

-- © Bill Steber | Special Submission To The LedgerBill Steber stood at the crossroads in the Mississippi Delta and made a deal with the devil that would allow him to not only master his photographic skills but become one of the most respected documentarians of Mississippi Delta blues. And kind of make a living (or at least fashion his life) while he’s at it.

When he made this deal, Bill knew time was running out to capture on his camera the West Africa-inspired blues culture of the Delta.

“I was racing against time to photograph these places (generally disintegrating juke joints and shotgun sharecroppers’ shacks) and these people before they all were gone,” says Bill, 50 (“almost 51,” he insists).

The longtime Nashville-area journalist – born in Grinder’s Switch, home of the late Sarah Cannon’s “Minnie Pearl” character – has dedicated this most recent half of his life to making sure to capture the images of Delta blues men and women and their culture.

Well, I exaggerated more than a bit about his deal with the devil. It’s not true, he insists. Still it would help to explain how he has been able to befriend these men and women and collect their images and their living history…. quite an accomplishment for a bald, pale-skinned, white guy who traded in the constantly worn Lennon-style Greek fisherman’s cap of his newspaperman youth for a more Delta-afternoon-friendly straw fedora.

It’s not like he blended in with these battered-by-years men and women, whose hard-scrabble lives – combined with the syncopation of the music and culture brought here by their slave ancestors – gave birth to this form of music we call the blues.

Bill laughs at his own audacity in inserting himself smack-dab into this culture and achieving the trust of the people in the Third World Country that was the Mississippi Delta before the arrival of Walmart, 24-hour gas stations, casinos, Big Mac factories and other modern intrusions.

“Here’s this white boy, driving into town in a car better than theirs, with his expensive camera equipment, wanting to photograph them.

“For some reason I was able to build beautiful relationships with them,” he recalls. “I’ve never taken that gift for granted.”

The ancient bluesmen he’s been photographing and speaking with for the most part are successors of and sometimes even disciples of Robert Johnson, the iconic Delta bluesman who, according to more than one account, met a dark figure (I’ll carefully call the guy “Mr. Satan,” just in case) at the crossroads and sold his soul in exchange for becoming an unmatched blues guitarist and storyteller.

Johnson – who at 27 died of complications from syphilis or from strychnine-dosed whiskey proffered him by a jealous husband (depending on who you believe) – trekked from juke joints to brothels to the beds of his fans. He was the live-fast, die-young blues equivalent of country music’s Hank Williams, in that he didn’t “invent” his genre but gave it a whiskey-soaked, loin-satisfied identity.

Eric Clapton – the best-known rock-era disciple of blues guitar (who early in his career lived a life that would have made Johnson proud) – points straight to the crossroads when discussing his influences. Johnson, he said, was “the most important blues singer that ever lived.”

Keith Richards – part of a nifty little outfit called “The Rolling Stones,” who first fashioned themselves as blues performers, recreating the classic stuff long before “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” became a gas, gas, gas – first heard a Robert Johnson recording while hanging out at his self-destructive cohort Brian Jones’ house.

His memory of what he learned that day: “You want to know how good the blues can get? Well, this is it.” (It should be noted that The Stones are returning to their blues roots for their next studio recording).

The legend goes that Johnson – who sounded like an entire band when he played and sang – sold his soul at the mythical “Crossroads” to gain those skills.

Bill just laughs that off. “There’s not JUST ONE crossroads” in Mississippi, he says when asked where the satanic majesty’s deal with the bluesman went down. “There are crossroads all over the place.”

While he insists he made no deal with ol’ Lucifer, Bill did make a deal with himself to work hard to vigorously chronicle a dying breed of blues players, a generation nearing extinction, while he had the opportunity. Some of these people actually had heard and learned from Johnson. Others learned from his disciples.

Their own final journeys were “on the clock,” to borrow a phrase. Time was running out for them to be captured in words and photos before they were sent, not to a crossroads, but to repose beneath the Mississippi soil tilled by their slave ancestors.

“I started in 1992, which was when I made my first trip to the Delta,” says the photographer. “And I spent 11 years documenting what I saw and who I saw down there.

“Two or three were dead within a month of when I shot them. People were dying off so quickly that I could hardly meet people before they were gone. These are the last of the people to have known Robert Johnson, the last generation that grew up with that culture.”

Tintype portrait of Bill Steber

-- ©P. Casey DaleyThese guys were not Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf nor B.B. King, all of whom fled the Delta for bright lights, big cities.

They were everyday people who loved home and hearth but who also could light up the night at a road-side Mississippi dive. As anyone who has visited Mississippi will vouch, most of these dives have either been obliterated or, at the very least, stand silent and rotting beneath the unforgiving Delta sun.

When pressed for an example of the on-the-cusp-of-death generation he was trying to document, Bill’s voice lilts as he tells the story of Scott Dunbar, a practitioner of the crossroads-flavored music.

Dunbar’s father was born a slave.

“Scott Dunbar made one commercial recording and a handful of field recordings” (for musical archaeologists), Bill says. “He was kind of a folk-blues guy who lived in Lake Mary, Louisiana – his daughter lived in a house-trailer next to the old house – but he was in Woodville, Mississippi, when I caught up with him.

“He was more or less a footnote in blues culture. He would have been 95, 97 years old. I decided I’d go down and find him.

“There was a childlike innocence in his music and in his persona. His album long since was out of print, but his daughter gave me a copy.”

Bill draws a long breath before accelerating the excited pace of this conversation.

“I spent some time with him, made a lot of pictures. About two weeks later, I was talking with Jim O’Neal, the founder of Living Blues (the University of Mississippi’s more-or-less official publication of the blues, for which this writer serves as Tennessee correspondent) and owner of Rooster Blues recording company in Clarksdale, Mississippi.

“I told him I met someone down in Woodville, Scott Dunbar, and I was told ‘He’s dead.’ I said: ‘He couldn’t be. I just saw him. ...’ and I was told ‘He died this morning in Woodville,’” Bill says.

That news reinforced an existential belief that Bill recites often in conversation and as deadpan as if it is Scripture.

“In Mississippi, I learned about faith, serendipity and that if you trust the universe, it will take you where you need to go,” the photographer says.

One place he needed to be was down on Highway 61, the so-called “Blues Highway” that connects the Delta to Memphis, the thoroughfare in the trek of the blues from backwoods Mississippi and to the world.

(My friend, Dennis McNally, the Grateful Dead’s official historian, has written an entire book, On Highway 61, about the important role that highway continues to play in American music.)

Bill’s 1992 immersion in the blues came about because The Tennessean newspaper had dispatched him to Mississippi to shoot the Natchez Trace Parkway, the 444-mile refurbished and resurfaced trade route from Nashville to Natchez, Mississippi.

“9 Foot Sacks,” Abbeville, MS 1996

Floyd and Leona Hollman hand pick cotton on Hollman’s farm in Abbeville, MS and place it in traditional 9-foot cotton sacks, which drag behind them — an extremely rare sight in late 20th Century Mississippi. Hollman said he still liked to pick some of his cotton crop partly because he enjoyed the work and partly because he got a higher price for clean cotton. In his younger days, Hollman claimed he could often pick 300 pounds of cotton in a day, but by his late 80s Hollman said he had to slow down some, and could only pick 100 pounds a day.

-- © Bill Steber | Special Submission To The LedgerIt is a boring drive (I’ll attest to that after my own trips to Natchez), so instead of taking the Trace to return to Nashville, Bill drove back on Highway 61, that artery of American music that actually connects New Orleans to Minnesota.

The Zimmerman kid from Hibbing, Minnesota – who created “Bob Dylan,” a guitar-strumming mash-up of Woody Guthrie, Kerouac, Ginsberg and Presley – titled his sixth studio album Highway 61 Revisited. The title song perhaps is as cryptic as any old blues song, in which slave protest and African-American discontent were disguised in work songs:

Oh God said to Abraham, “Kill me a son”

Abe says, “Man, you must be puttin’ me on”

God say, “No.” Abe say, “What?”

God say, “You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin’ you better run”

Well Abe says, “Where do you want this killin’ done?”

God says, “Out on Highway 61”

Of course, Zimmerman – who nowadays mostly sings works from the great American songbook, in which he comes across as a sort of streptococcal Sinatra – borrowed from anybody and all styles, including the blues, when he created that “Bob Dylan” persona.

It was out on Highway 61 where Bill discovered his calling, his passion and profession. His future.

“I was coming up old 61, passing through Tunica County. There was this enormous storm on the horizon. I knew the storm would be upon me soon. I got into Lake Cormorant, and there was this little old shack and this man is out in a truck patch, chopping weeds out of his vegetable garden that’s on the edge of this huge cotton plantation.

“I wanted to get something in the foreground of the picture with the lightning in the background, so I jumped out of my car and went to talk to Mr. W.C. Miles. I said: ‘You can stand with your hoe and with the storm in the background, I’ll take the picture.’

“He was very patient. By the time I got the 12th picture, I jumped in my car and took off (because of the violent weather). When I got home, I had this print, W.C. Miles with the shack and the lightning in the background.

“I could have gotten any old guy holding a hoe up in the storm, but I found someone who actually did that…. He felt important.”

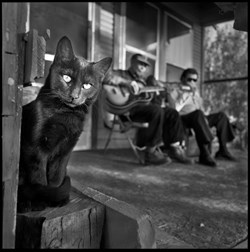

“Bentonia Blues,” Bentonia, MS 1993

A black cat stares out from the front porch of blues singer Jack Owens as he plays his dark and haunting blues with harmonica accompanist Bud Spires. Owens, whose canon of songs comes from the minor-keyed Bentonia tradition made famous by the delta legend Skip James, sings in his signature song, “It must have been the devil, changed that woman’s mind/ I’d rather be the devil than to be that woman’s friend.” Songs in the Bentonia tradition are suffused with brooding images of the supernatural. Robert Johnson drew from this tradtion in composing his most haunting blues, “Hellhound on my trail.”

-- © Bill Steber | Special Submission To The LedgerTo Bill he was more than important. W.C. Miles was life-changing.

“I went back a few months later to give him a print and I couldn’t catch him. He had moved out of the house.

“But then I started asking around. He had moved a few miles away, into a nicer brick house. He says ‘that’s so beautiful’” when presented the print.

“I was just talkin’ to him. I said: ‘Man, W.C., you don’t know music by any chance?’ And he says ‘My Daddy is Willie Coffee. He ain’t dead. He’s alive.’”

Coffee, a friend of Robert Johnson, was someone Bill couldn’t wait to meet. Literally.

He knew the man was getting old, and Bill’s heart now was filled with determination to preserve this culture, this history, these bluesmen.

“So I come down on a Sunday afternoon. I go over to this little house. There’s Willie Coffee, as handsome as he could be, in his early 80s.”

Bill and Coffee hit it off, and not only was there a photo session, Coffee told him about his friendships with other Delta blues greats, like Son House, Charley Patton and Willie Brown.

He told Bill “‘My main man was Robert Spencer. You may know him as Robert Johnson….’

“He told me so many tales of Robert Johnson. He said ‘that n….. can play.’”

“He had no idea of what a big name Robert Johnson was.”

That visit reinforced Bill’s belief that Mississippi was his destiny. And he promised himself he’d devote his life to photographing “the old ways,” the blues culture – what was left of it – before it all was gone.

All these years later, he still makes that trek to the Delta. But change has come, symbolized perhaps by the way anonymous mobile homes, car lots and other businesses have replaced the old shotgun shacks and juke joints where people lived and sang the blues.

Bill accomplished his mission of making sure those who knew Robert Johnson, or ordinary folks who sang slave songs in the cotton fields, were interviewed and photographed, their culture preserved.

“A lot of the way the whole thing worked: All of that happened because I was looking for a foreground for a picture of a lightning storm.

“It is another example of the serendipity I’ve always found in Mississippi.”

Another example was his meeting with Son Thomas, at his home in Leland, Mississippi, where a casket and a Styrofoam-headed “corpse” – a dark and strange display of folk art – filled the living room.

“Son, impossibly rail thin, was sitting on the edge of his bed. He’d just got out of the hospital for brain cancer. He came out and played some songs and sang in this high falsetto.

“Meeting Son was one of the greatest things that ever happened to me.

“I don’t know about reincarnation, but if I did, I knew I was born (in the Delta). I was determined ‘I’m coming down here as soon as I can.’”

A one-year grant allowed him to do just that from 1999-2000, when he took time off from The Tennessean to focus on the Delta.

“I was going there for three or four weeks at a time, then coming home” to rest and prep for another trek.

He returned to The Tennessean, but not for long.

His father died, and while he was at that funeral with his wife Pat Casey Daley (also a great photographer), they got a call that her father had just died.

“We figured it may have been the universe telling us to get on with our lives,” he says.

This time he really was at a crossroads, but the decision had pretty much been determined by the many fortunate happenstances, that serendipity he found in Mississippi.

He made good money at the newspaper, but he knew it was time to leave and return to the Delta, to literally focus on those slaves’ descendants and their music before the inevitable victory of steam shovels and Whoppers with cheese.

Eventually, during his pursuit, he left the modern, digital and sanitized photography style that made him a valuable newspaper photographer behind.

To give his beloved Delta subjects classic dignity, he changed to wet-plate collodion photography, best-known perhaps for its use during the Civil War.

To take these shots, the photographer ducks beneath a black cloth to focus and then exposes the image onto a black metal plate.

Bill gets a bit sentimental and existential when he explains the pull he still feels after all these years of collecting photographs, memories and artifacts in the Mississippi Delta.

“I got pictures of the last rural juke joints, river baptisms, hoodoo stuff. … All the things that went into the creation of the blues,” he says, a gentle pride dancing in his voice.

No, Bill didn’t need to make a deal with the devil when he proudly took the turn at the career crossroads to focus on his promised land and take photographs for record jackets, books and other publications. It was his life, but not his living.

“I’ll never make back the money I’ve spent. If I have a print sale I’ll always cut the subject in on it too.

“I see myself as a champion of the culture, pointing other people toward the real thing.”

For survival, he works as a contract photographer and musician.

“In Mississippi, I learned about faith. Serendipity. That if you trust the universe, it will take you where you need to go.”