VOL. 40 | NO. 36 | Friday, September 2, 2016

The fading accuracy of political polling

By Sam Stockard

Joe Carr says he couldn’t believe the deficit when U.S. Rep. Diane Black trounced him in the August election to recapture Tennessee’s 6th Congressional District seat.

Black, a third-term incumbent, captured 63.6 percent, 33,110 votes, to Carr’s 32 percent, 16,662, in a race he says early polling showed as “very competitive.”

“I was stunned,” says Carr, who came much closer to defeating U.S. Sen. Lamar Alexander in 2014. “I was also stunned because of record low turnout.”

Carr speculates many people who were first-time voters and backed Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump in March failed to return to the polls, even though they were saying they would vote again in the congressional primary.

The former state House Republican from Lascassas says he used the same pollster, an Oregon firm, as he did two years ago when he ran against Alexander. Its numbers were accurate in 2014, but his problem was a money shortage at the race’s end when the longtime Republican leader poured it on.

Against Black, Carr also faced a serious financial deficit, and bad polling information certainly didn’t help.

“I don’t know what the answer is,” says a confounded Carr, who is also uncertain where his political life might go next.

One thing he seems certain about, though, is the inaccuracy of pollsters.

“They are having a harder time polling than ever. I believe polls are less accurate now than they used to be,” he adds.

Though polling experts say the numbers can work if tweaked correctly, the increase of cell phones, which do not have listed numbers, and the disappearance of land lines is causing problems for pollsters trying to obtain a random sample, one that would give them a snapshot of the voting public.

Yet incumbents and political challengers aren’t giving up on polling. Quite the opposite. There are so many pollsters at work that voters are being “bombarded” nearly every night, Carr says. “It was getting ridiculous.”

Carr isn’t the only person with doubts about poll results.

“I think polling is unquestionably less accurate now than it was 10 years ago and certainly 20 years ago or 30 years ago,” says Dave Cooley of Cooley Public Strategies, a former staffer for two-term Tennessee Gov. Phil Bredesen, also mayor of Nashville from 1991 to 1999.

Political polling started becoming more segmented when people began using unlisted phone numbers, requiring pollsters to use random digit dialing to obtain a random sample, Cooley says.

The next big gap in accuracy came when people latched on to caller ID, enabling them to screen phone calls by avoiding unfamiliar numbers.

Then, the advent of cell phones caused even more problems, since those numbers aren’t listed, requiring the people who conduct surveys to dial numbers by hand, which takes more time and costs more money, experts say.

Another strike against polling is time. People simply don’t want to sit down for 20 minutes to take a questionnaire, whereas years ago, people were more willing to participate in 30-minute surveys, allowing pollsters to obtain more in-depth information.

People who answer the phone also could be more “sophisticated” about polling and sometimes choose to “game” the poll by not telling the truth, Cooley explains.

“So you’ve got all these factors just layered on that have driven the accuracy of polling, I think, to an all-time low,” Cooley says. Twenty-five years ago, he adds, candidates could bank on polling numbers and use them for strategy with a much “tighter” margin of error.

Political candidates seeking “pin-point accuracy” these days probably need to look elsewhere, but polling works for those who want to know voter trends and can afford a good-sized margin of error, he says.

Academia view

Richard Pacelle, head of University of Tennessee’s Department of Political Science, isn’t quite as jaded about polling as Cooley and Carr, pointing out candidates use their own “highly sophisticated” polling to reach target audiences to determine where they will campaign and buy advertising.

Richard Pacelle, Ph.D., professor and Head of the Department of Political Science at The University of Tennessee, researches public law, judicial politics and research methods.

-- Adam Taylor Gash | The LedgerDemocratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton, for example, hasn’t bought any ads in Colorado or Virginia because her campaign’s polls show she’s so far ahead in those states no money needs to be spent there, Pacelle says.

“Most of what they’re trying to do is reach certain audiences,” Pacelle notes.

Clinton, for example, wants to make sure African-American and Latino voters will understand the importance of turning out on Election Day. Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump, meanwhile, is targeting Reagan Democrats, those concerned about a weak economy.

At this point, the Clinton campaign is further ahead in its organization than the Trump campaign, and in battleground states such as Florida and Ohio is polling every four to five days, Pacelle says.

Trump hasn’t spent nearly as much money yet on polling, he points out, adding he can get a lot of free media time. Republicans may need to work on their polling expertise, as well.

“The Obama people really perfected (polling) two elections ago. And I think this is one of the places the Republicans are behind,” Pacelle says.

Four years ago, Republicans tried to catch up with Democrats in terms of presidential polling when Mitt Romney ran against Obama.

But they didn’t weigh the results properly and thought they would win by 2 or 3 points. Instead, they wound up losing by 4 or 5 points, he says.

Pollsters say cell phones should make up anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of the mix in a survey, depending on the type of campaign or poll.

In fact, the Pew Research Center says it is increasing cell phone interviews to 75 percent from 65 percent in its 2016 telephone surveys since nine out of 10 U.S. adults have a cell phone and the percentage of those with cell phones only has gone up “steadily” over the last 12 years, according to the organization’s website.

MTSU professor Ken Blake, who handles the university’s poll with Jason Reineke, says including cell phone numbers in a sample is “very important” because of the rising proportion of Americans and Tennesseans who rely exclusively on cell phones.

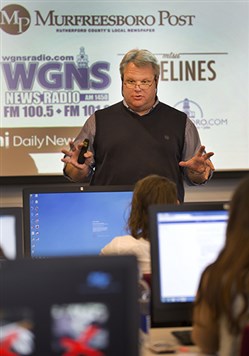

Ken Blake, Ph.D., associate professor of journalism at MTSU, also is operations director for the MTSU Poll, a once-a-semester telephone poll measuring the opinions of residents living in the 39 counties that constitute Middle Tennessee.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“If all you’re doing is sampling land-line numbers, then you’re not going to reach those people,” Blake explains. “And the problem with that is people who rely exclusively on cell phones, they tend to be younger, they tend to be more Hispanic, they tend to be from more metropolitan areas, as opposed to rural areas.

“So if you don’t poll cell phones you end up under-representing those groups, and so that’s a huge problem.”

But simply locking in on cell phones won’t work either.

Nationally, 47 percent of U.S. adults have a cell phone only, according to the Pew Center, so the nation hasn’t quite reached the point of completely cutting off land lines. Those are likely the people who still eat supper at 6 o’clock and watch TV news.

If polls don’t use the right mix of cell phones and land lines, segments of the population will be under-represented, Blake says.

Making the situation harder for pollsters is that seven out of 10 calls to a land line come from a telemarketer or similar caller, which keeps many people from answering the phones, he adds.

“It’s one reason that response rates for polls have been dropping steadily for about the past decade. … A pretty good response these days is 5 or 6 percent,” Blake points out. “There’s quite a bit of research going on in the field to try to figure out the effects of those declining response rates.”

Despite those barriers, the MTSU Poll has been pretty successful predicting outcomes.

For example, polling ahead of Tennessee’s Amendment 1 dealing with abortion in 2014 proved accurate, predicting the measure would pass. Lawmakers subsequently enacted laws putting more restrictions on abortion clinics.

In January 2015, the MTSU Poll checked on Insure Tennessee, a proposal by Gov. Bill Haslam to provide a state-sponsored insurance program for about 280,000 people caught in a gap between TennCare and the Affordable Care Act.

Ken Blake helps junior Tradesha Woodard during one of his classes at MTSU.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerThe survey found about two-thirds of Tennesseans had heard very little about the proposal. Of those who knew something about Insure Tennessee, 49 percent favored it, while only 11 percent opposed and 40 percent weren’t sure.

“When two out of three adults in the state haven’t really heard about Insure Tennessee, it’s really kind of hard to draw much of any conclusions about support or opposition,” Blake says.

During a special session on the matter, many legislators used the reasoning they didn’t have enough information to support Insure Tennessee. Ultimately, the measure failed to reach the Senate or House floor for a vote in the Legislature.

In early 2016, the MTSU Poll found 33 percent of Tennessee Republicans named Trump as their leading presidential candidate. He won the primary with 38.9 percent of the vote, 14 percentage points better than runner-up Ted Cruz.

“Accuracy in polling is always a moving target where we’re responding to changing conditions and always trying to pursue best practices. But so far we seem to have a pretty good track record,” Blake adds.

On the front lines

As the presidential election approaches, Pacelle says national polls are starting to tighten, with Trump drawing a little closer.

Paying attention to the way polls are conducted will be crucial at the stretch drive approaches.

For instance, some polls show Trump getting none of the African-American vote or 36 percent of the Latino vote, neither of which will come true on Election Day, Pacelle says.

In those instances, part of the “sophistication” within polling is weighting the polls to make sure they reflect the population, he points out.

But it becomes even more nuanced.

National pollster Brad Todd, who handled Congressman Black’s campaign polling, says the size of the cell phone sample depends on the campaign and the region.

In rural areas, he’s comfortable with 25 percent because more homes in those regions are likely to have land lines. But for a general election in a metropolitan district, a pollster needs 35 to 45 percent of the results to come from cell phone calls, he notes.

Because of increased cell phone use and the accompanying attention deficit – people are so busy on their phones they don’t have time to talk – surveys also are dropping from 30 minutes to 18 minutes. Less information can be gleaned from questionnaires, thus forcing pollsters to take even more surveys, which drives up costs.

Lists of cell phone numbers can be obtained from companies that create them using area codes and exchanges dedicated to cell phones, according to the Pew Center.

To interview cell phone users, however, the surveyor must dial the numbers by hand, instead of using a machine, which takes more time and costs more money, Todd explains.

Consequently, campaigns and media outlets likely to rely on mechanized calls are going to see their accuracy take a hit. High costs aren’t likely to affect polls taken by larger news organizations such as the Washington Post or ABC News.

Getting picky

Proper polling means more than compiling a batch of numbers.

Reading the figures to ensure the candidate makes the correct move requires some tricky adjustments.

In fact, polling too many cell phone users in non-presidential races can be dangerous, according to Steven Reid, who handled strategy and management in Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland’s 2015 campaign victory over incumbent Mayor AC Wharton.

Some pollsters increase the number of 18- to 35-year-olds in their polling data by “striving” to get 20 to 25 percent cell phone users. But that demographic group drops significantly in elections such as the most recent state and federal primary, Reid says.

“So oftentimes when I get back a poll, I read just the numbers based on what trends are developing in early voting and what trends have historically happened in the area where the election’s taking place,” he adds.

Todd says candidates don’t use polling to find out who’s winning the race as much as they do to set the tone for their campaigns. They can’t say everything, so poll results let them know what’s on people’s minds.

Once an initial benchmark survey is done, candidates can find out what’s on voters’ minds, then shift strategy as follow-up polls are taken.

In the finals weeks leading up to Black’s race against Carr, she ran TV ads touting her rise from meager beginnings, including changing her own muffler, and questioning Carr’s residency outside the 6th Congressional District along with his seeming constant campaign to win an elected seat. Carr had dropped a run against U.S. Rep. Scott DesJarlais to run against Alexander in 2014 before challenging Black this year.

“We don’t work for candidates who need a poll to tell them what to believe,” Todd says. “But smart candidates do use polling to help them order their messaging and be a little bit more disciplined.”

The numbers showed Black’s message was reaching voters, and even before the final results were counted, Todd was “very comfortable.”

Longtime Democratic pollster Alan Secrest says the key to polling is giving the client “the courtesy of candor,” which too often is missing.

“Really, accuracy would be the minimum expectation for a pollster. That should be a given, and then beyond that comes analysis and direction in terms of message and strategy and tactics,” says Secrest, a pollster for three decades. “There’s been a dumbing down over the years in what is expected from polling.”

Polling can be plagued by sloppiness and, in some cases, cheap surveys, a lot of which are done by media outlets that don’t want to spend much money, Secrest says.

Some might try to measure the electorate by looking at registered voters instead of “likely” voters, he points out. Respondents must be screened correctly to ensure the poll’s accuracy, but that can also be an expensive proposition.

“If we’re talking about politics, all we care about are likely voters. Everything else we set aside,” Secrest explains. “You try to create a universe, a list of eligible phone numbers of people that are likely to turn out.”

Surveys can be weighted too much and wind up reflecting the population, instead of those who are going to go to the polls, he says.

Secrest reports he polled for a political action committee last year in the midst of the Memphis mayoral race between Strickland and incumbent Wharton.

While some other private surveys were showing that race within 5 points, he says his mid-September survey – three weeks before the election – showed Wharton at 22 percent, where he finally wound up, and Strickland at 34 percent, with other candidates dividing 25 percent and 19 still undecided at that point. Strickland’s margin grew as he gained support from undecided voters, Secrest says.

“The more numbers you have to burn through, the more expensive the survey is, even though the goal is accuracy. And too many times we see firms purporting to do accurate polling cutting corners,” Secrest explains.

Yet even as the world of polling changes, largely because of cell phones, Nashville-based consultant Cooley foresees a day when pollsters might not have to worry about getting the perfect mix.

He points toward his 90-year-old father, who has no technological skills and doesn’t use email or social media. In fact, he doesn’t even use a computer. But he has a cell phone and uses it.

Eventually, Cooley says, “It may go full circle and make it more accurate again or a little more accurate than it is.”

Sam Stockard can be reached at [email protected].