VOL. 40 | NO. 29 | Friday, July 15, 2016

Got a food crisis? Blue Bell shows how to regain public trust

By Hollie Deese

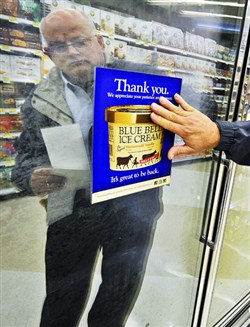

Reflected in a freezer door, Dennis Olson fixes an adhesive sign thanking customers for waiting for the return of Blue Bell ice cream on its first day back in stores on Dec. 14, 2015. Several flavors, manufactured at plants in Oklahoma and Alabama, rolled out to 170 stores after a bacterial infection was found in ice cream from several plants, prompting a recall and company-wide shut-down.

-- Andrew D. Brosig/Tyler Morning Telegraph Via ApIf food recalls seem to have you cross-checking your pantry or freezer more often, it’s likely you are.

A quick look at the latest listings on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration website shows 108 recalls from May 11 through July 9 this year. The list includes items you could find in any home in Tennessee – Krusteaz Pancake Mix at Kroger that may be contaminated with E.coli, macadamia nuts from Whole Foods Market with salmonella – even Dollywood Cajun Mix with listeria.

No manufacturer, it seems, is immune to a food safety crisis, no matter how well-known or reputable. It’s not a matter of if it will happen, but when.

And what matters when bouncing back from a blow to the reputation is how the company handles it from the start.

On March 13, 2015, venerable ice cream producer Blue Bell sent out a letter to customers following a product recall linked to a potential listeria problem, first detected during a routine sampling program by the South Carolina Department of Health and traced to a manufacturing plant in Broken Arrow, Oklahoma.

The first line of that letter read, “For the first time in 108 years, Blue Bell announces a product recall.”

That opening line, which capitalized on the company’s long record of operation and safety, was just the beginning of a public relations battle that coincided with the regulatory investigation. Ten people were ultimately sickened from affected items distributed in 23 states, including Tennessee.

Throughout the process, three Blue Bell manufacturing plants were temporarily closed and inspected. Ultimately, all products were pulled from the shelves in an abundance of caution.

At the end of it all, the FDA reported that there were three deaths in Kansas associated with the recalled products from Blue Bell.

But the company released information every step of the way, offering full transparency of what was happening, and the company’s loyal customers actually responded with understanding.

Grabowski

It’s a consumer response almost unheard of in food recalls when people are quick to blame, says Washington, D.C.-based Gene Grabowski, who handled the crisis management of Blue Bell.

But Blue Bell’s brand loyalty almost gave them a protective bubble, something not afforded newer companies, or even more established ones with shakier track records.

“Blue Bell has one of the most powerful brands in the country,” Grabowski says. “When Blue Bell announced its recall, consumers were calling me saying, ‘Oh, this is so terrible that this would happen to a company like Blue Bell.’

“Nobody blamed Blue Bell. But not like when Chipotle or ConAgra or General Mills or any other company goes through a recall, even with good, strong brand recognition.

“It may be the only recall I’ve worked on out of hundreds where consumers actually did not blame the company in great numbers.”

Grabowski went so far as to say the only other brand he has seen that rivals Blue Bell for customer loyalty is Harley-Davidson.

“Harley-Davidson devotees tattoo the logo of the Harley-Davidson on their shoulders,” he says. “When your customers start doing that, you can stop marketing.”

Recalls growing

Grabowski is a partner with kglobal, a full-service communications firm that handles high-level strategic communications programs, media outreach, digital and social media campaigns and crisis communications for athletes, celebrities, executives and companies.

A former journalist who reported on congressional issues for The Associated Press, Grabowski specialized in labor and manufacturing issues, and covered stories like the U.S.-Soviet arms treaty summits and the Supreme Court nomination of Judge Robert Bork as the White House reporter for The Washington Times.

These days he helps companies get ahead of crises instead of reporting on them, and he’s good at it. He has handled 176 food and consumer product recalls over the years, earning PR News Crisis Manager of the Year Awards for his work on various campaigns, including the global lead-paint-in-toys recall and the North American recall of pet foods.

Grabowski’s clients are almost always handling extremely sensitive, high-stakes issues while under intense media scrutiny, regulatory pressure and litigation. Grabowski says he handles about 15-20 recalls a year because not only are there more recalls now, they are more noted by consumers.

“The technology now exists where we can track foodborne illness better than ever before, and the FDA and USDA and Consumer Product Safety Commission have all started to crack down on companies, whether it’s food or consumer products or drug companies, because the internet changed everything,” he explains.

‘‘Consumers are now more active, Congress has gotten more involved, so there’s more pressure on the regulatory bodies to act more severely and more swiftly.”

In 2008, Congress passed the Food Safety Modernization Act (FSMA) and that was done in response to the sheer number of recalls in 2007 regarding lead paint in toys, pet food recalls and a record number of food recalls.

“We had several hundred, and so Congress was being motivated by a very active consumer base,” he says. “They put the FDA’s feet to the fire and they passed that legislation.”

What makes Grabowski especially adept at handling food recalls like Blue Bell is his food background as the vice president of communications and marketing for The Grocery Manufacturers of America, the world’s largest food trade group, where he directed the organization’s outreach to national and global regulators.

Personality a plus

From the moment a recall begins, it is time to start jumping hurdles. Newer companies or those in somewhat faceless industriesy like oil or pharmaceuticals face higher hurdles.

Blue Bell succeeded where others might fail because they have a history built on hard work and handshake deals.

“Blue Bell walks the walk,” Grabowski explains. “Blue Bell is a trusted business partner with retailers. Retailers love Blue Bell. Retailers were as anxious as the consumer for Blue Bell to come back because it’s such a popular brand, and they like the Blue Bell people.

“They’ve built the brand over 100 years of being good, steadfast, reliable, trustworthy citizens, and it shows in their product. They’re consistent in their quality. They’re consistent in their service. It sounds simple, and it is, but Blue Bell built its brand day-by-day.”

In fact, when Ohio-based Jeni’s Ice Cream had a recall just a few months later, Grabowski says, it was able to benefit from the steps Blue Bell had just gone through. Its customer loyalty and personality helped the company recover in consumer’s eyes.

“Jeni’s went to school on watching Blue Bell, and so they knew what to do right and what not to do,” he notes.

“They also got out in front of it and did a lot of positive publicity, even during the crisis, and they’ve got a lot of good strong fans, too.”

Chipotle had personality, too, but it has had trouble recovering once-loyal customers after being hit with a series of food contamination scares in 2015.

On July 8, The Washington Post reported the chain had a 29.7 percent drop during the last quarter at restaurants open more than 13 months. That’s significant.

“Two things happened with Chipotle,” Grabowski points out. “One, nobody expected them to (cause) foodborne illness, so their customers felt betrayed. Two, there was a lot of jealousy in the marketplace from competitors saying, ‘How dare they say that their stuff is better or fresher than ours?’ And so when something bad happened to them, a lot of knives came out.”

Grabowski says Chipotle has ultimately begun to get a handle on their crisis in the last few months, closing stores for food training and more, but the damage had already been done.

“The first couple of months, they blew it unfortunately,” he adds. “But you can find a flaw in any company’s way of doing it, even Blue Bell. The question isn’t whether a company handles a recall perfectly. It’s a question of whether a company handles a recall well enough.”

And, if it is proven in court that food safety issues were knowingly compromised, jail is becoming a reality.

Take Stewart Parnell of Peanut Corporation of America, for example. The former CEO was convicted on federal conspiracy charges in September 2014 for knowingly shipping salmonella-tainted peanuts to customers.

That salmonella outbreak killed nine people and sickened hundreds.

He was given a 28-year sentence. His brother, Michael Parnell, was given a 20-year prison term.

Social media changed the game

Everything changed for over-the-counter medication safety standards in 1982 when several people were killed in the Chicago area by Tylenol capsules that had been laced with cyanide after being placed on store shelves.

The incident led to federal anti-tampering laws and packaging reforms, and Johnson & Johnson’s response has been considered exceptional.

But Twitter and Facebook weren’t in place during the Tylenol scare. Social media can exacerbate the situation and incite a barrage of consumer insults and bad reviews.

“If Tylenol happened today, it would not be considered a success story,” Grabowski says. “It took weeks for them to act, but by the standards of the day acted swiftly.

“Still, the company did a couple of things really well. The CEO got involved, and they introduced the tamper-resistant seal. That was a brilliant stroke. When you’re in a crisis like that, if you can come up with a solution that’s revolutionary, they overshadowed the crisis with some real news.”

Plus, they had an automatic villain. Somebody was tampering with their product. The company itself was not responsible.

Today, companies can kill their reputation in the face of crisis if they are too slow to make a statement, too slow to reassure consumers and too slow to tell consumers and regulatory agencies what they’re doing to fix the situation.

“You have to move faster,” Grabowski points out. “You have to pay attention to Twitter and Facebook and Pinterest and Instagram. You have to monitor them more than you monitor the news media.”

“One thing that we suffer from today is that we are grading these companies based on their recalls in real time, before letting some time pass, and it’s unfortunate,” Grabowski says.

“It’s not about perfection, it’s about doing well enough under the circumstances.

“I’m a big believer that when you’re in a crisis like that, you rip the Band-Aid off. Get it over with. Come clean. People will accept crisis. People will accept recalls. “What people will never accept is a cover-up.”