VOL. 40 | NO. 22 | Friday, May 27, 2016

Irony has 99-year-old neighbor in 12South

Since 1963, Alvin M. Fitzgerald has been sitting on his porch, watching his neighborhood change. He really doesn’t like the way it’s changing now, but he’s not going to let developers tear down the house and fill the Caldwell Avenue lot with “modern” housing.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerAlvin M. Fitzgerald has earned the right to put the issue of what’s happening to his neighborhood in black-and-white terms. Literally.

When he moved his family into the house on Caldwell Avenue 54 years ago, they were about the first African-Americans in that nice, white, middle-class neighborhood.

Then came “white flight,” and the neighborhood turned into a proud enclave of mostly black families. Now, well, he’s watching it turn white again as old homes are destroyed and replaced by modern condos, town houses and the like. Others are gutted and completely renovated.

“It’s turning back to how it was when we moved in here,” says the gentle 99-year-old as he relaxes in his spacious living room.

He knows there’s nothing he can do about it, except sit and watch what’s happening around him from his porch or by looking through the sheer curtains to see – and ignore – developers who walk up his sidewalk and knock on the front door.

He doesn’t even want to listen to big-money offers for his beloved family home.

“They’d just tear it down and put two or three of those new ‘houses’ here,” he says, shaking his head.

“I look through (the sheer curtains), and if I don’t recognize who it is I don’t open the security door,” he adds, a few minutes after he unlocks the wrought-iron security door – the black metal also covers the narrow sidelights – and lets me into his white house at 1003 Caldwell Avenue.

“This is the Waverly neighborhood,” Alvin answers my question. “Some call it Waverly-Belmont. But Belmont’s over there,” he says, pointing to the other side of 12th Avenue South, which traverses the hilltop a couple of hundred yards from where he and wife, Addie, have lived for more than a half-century.

He smiles, softly, and semi shakes his head. “Course now they are calling it all the ‘South 12th’ or ‘12 South’ neighborhood. Everything’s changing.

“They’ve got all those restaurants and stores up there now. Used to be houses. Now there are those big, tall buildings with three or four apartments in them, too. I wouldn’t have one of those. I like living in my house.”

He leans back in a chair near the living room wall lined with pictures of his eight children (ages 56-72), “about 25” grandchildren and perhaps some of his great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. He embraces family, friends and faith, while making every moment matter at least as much as his legacy.

“I’m 99. Almost 99½. Don’t do you no good unless you live to be 100,” he adds, a slight smile cracking the face of a man who seems at least 20 years younger than his number of birthday candles.

“I hope I’ve got a few more years,” he says softly, as a television plays somewhere in the back of the house. “Me and Addie – she’s not real young either, 93. We been married 73 years. We like to watch TV and fiddle around.

“And we don’t just sit at home. Sometimes one of our children will take us someplace. Sometimes I’ll drive my car to Mount Sinai Primitive Baptist Church, over on 14th and Tremont. I’ve been a deacon there since 1960.” He was baptized into that church the year before.

The car, he proudly proclaims, “is a 1994 Pontiac, and has only 70-some thousand miles on it.” To paraphrase the old used-car salesman’s pitch: This car truly has just been driven to church by a little old man on Sundays. (There actually are other days when deacon’s duties lure him behind the wheel).

The car is parked to the rear of his house, where a concrete driveway leads from the alley to the garage where he used to repair lawnmowers for extra money. Also in the back yard is a concrete patio.

“That’s where I walk on nice warm days.” He uses his hands to illustrate how he walks back and forth in the back yard, keeping circulation flowing and staving off – as well as possible – the natural ravages of age.

“Doesn’t do you any good just to sit around,” he explains.

In years past, he would go for strolls down Caldwell and turn onto the long sidewalk lining 10th South, through what was then primarily a black neighborhood.

Or perhaps he’d hike uphill – although it is a bit steep – to walk along 12th.

Now he doesn’t walk along the streets.

“It’s too dangerous out there,” he says of the city on the other side of his security door.

Magical Music City USA – even with its glistening condos, town homes and cluster developments sprouting like mushrooms after a late-spring rain – has too many punks of all races who tote guns, dope and death wishes. “It’s that way all over Nashville now. Doesn’t matter what the neighborhood is. Dangerous.”

The danger of this neighborhood that’s within easy reach of the projects and downtown – where giant cranes and skyscrapers arm-wrestle the Batman Building for control of Bob Dylan’s celebrated Nashville Skyline – is one thing that hasn’t changed much since I last wrote about Alvin.

“It was 15 years ago at least. Maybe 20,” he says, noting he has a clipping of the column I wrote about him back then, a tale I wrote for the city’s morning newspaper. “Don’t know where it is, though.”

At that time, a few well-heeled gentry, white “urban pioneers,” were starting to buy homes here, refurbishing them, beginning the trend that’s turned this street and surrounding blocks much paler in complexion than it’s been in a half-century.

Alvin and Addie chose this home back in 1963 because they wanted a more convenient, safer location to raise their family. “We had been living on Third Avenue North. Renting. This is the first house we bought.”

They, too, were urban pioneers, but of a different shade, moving out of historically black North Nashville and into what then was an almost lily-white neighborhood.

They weren’t doing it to make any sort of “we shall overcome” statement, although they surely had that right.

“We were just looking for a comfortable house for our family,” Alvin recalls.

Rich cooking aromas filter from the kitchen on the other side of the wall. “Our children are good to us. They all live out in Antioch. Sometimes one of them brings food here so Addie doesn’t have to cook.

“You know, she’s not so young either,” he jokes of the love of his life.

She did more than her share of cooking in this house over the last five decades-plus, feeding her hungry children, making sure her husband was well-fueled for his labors. “I had three jobs, but I didn’t see the money, because the old lady spent it taking care of the children,” he says, with a laugh.

The white people who lived all around them when they moved here “were really nice to us. Friendly,” says Alvin. “Then they started packing up and moving out.”

It was the era of “white flight,” basically a national “movement” in which white families moved their families to the “suburbs,” which back then were places like Green Hills, where post-war era houses also now are being bulldozed to provide space for so-called “McMansions” and their more diminutive kin.

The abandoned-by-whites Waverly turned into one of Nashville’s nicest enclaves of black-owned homes.

In the last part of the 20th Century or early in this one, anyone driving through here would see mostly African-Americans. Families toiling to display pride in their homes and yards. Perhaps they were walking down the sidewalks of 10th Avenue to the now long-shuttered neighborhood market, where I used to buy my lottery tickets after the state took over the numbers racket.

Now brand-new and sometimes precariously narrow homes – perhaps occupied by the descendants who partook in the white flight – spring up as quickly as the old houses are obliterated.

“There’s one up there that has a swimming pool on the roof,” Alvin points out, nodding toward “12 South” and its condos. “I wouldn’t want to live in those places. Too many steps. Young people don’t realize that they’ll get old.”

Across Caldwell from his own house, four homes jam a single lot where a middle-class house stood not long ago.

Many long-time residents here have sold or are selling their homes, taking chunks of money offered by developers, leaving Alvin and his family once again surrounded by mostly white people, this new generation of urban pioneers.

“They (developers) aren’t buying them because they want the houses. They buy them for the land. They’ll tear down the houses and build more of those,” Alvin says, as he nods across Caldwell.

Photos of multiple generations of Fitzgeralds line the living room wall in Alvin M. Fitzgerald’s house.

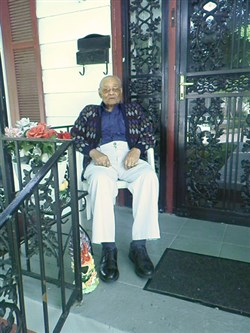

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerAt almost 99½, Alvin freely offers perspective on what is happening as he studiously observes it – on warmer days – from a chair on the porch where he also has offered occasional wisdom to a very random white journalist.

Cooler weather finds him behind the sheer curtains, but always keeping track of the changes.

He understands why his neighbors succumb to the moneymen. “Most of them been selling out,” he explains.

“They should take that money and go out in the country, away from here, and buy a house with it. But they want to stay in the city. So they rent these apartments for $1,200, $1,500 a month.”

Real estate windfalls quickly vanish. “Next thing you know is they are living in a box under a bridge.”

Alvin’s not budging. “They been bugging me about my house,” he says, noting that he has a stack of calling cards that have been left on his door by developers wanting to buy and demolish his house.

Of course, he seldom talks to them unless they catch him on the porch. Remember, he won’t unbolt the security door if he doesn’t recognize the faces on the other side.

He did, by the way, recognize me, although in a phone call before I went to his house, I warned him that I’m older and a bit shorter than I was the last time we hung out.

“I’m older too,” he answers. But when I get to his home, I notice he certainly has aged much better than has his visitor with the long, white hair.

The secret to staying forever young, living long and prospering?

“It’s in the Scriptures,” says this deacon at Mount Sinai for more than six decades.

“Obedient child, they shall be long on this earth. Disobedient child shall be short,” he says, paraphrasing Romans 2: 6-8. One version I found promises “wrath and fury” for those who are disobedient.

“I’m feeling pretty good for my age,” says Alvin, clearly the obedient type. “My friends from high school have all died off. I get about, but I can’t stand like I used to.

“My knees are pretty good, though. But I kinda have stiff shoulders from old Arthur,” he says. “Got Arthur-itis in my shoulders.” He lifts his arms to demonstrate that he still can move them just fine, though.

In addition to the Arthur-itis that is in my own shoulders, my life has changed quite a bit since we last had a long conversation. The bottom-line corporate mentality has forced me from the daily newspaper business and into the “wilderness,” where I fend for myself and my family as a freelancer and adjunct journalism professor.

Back when I was at the daily newspaper, across Broadway from the Tiger Mart, I’d drive by Alvin’s house every day, going to and from work.

If the weather was nice, Alvin would be on the porch. We’d swap happy waves as I drove past.

His plans are to live a few more years of retirement in this house, enjoying the quiet time after years of working as many as three jobs to pay for it.

“I worked 20 years at Phillips & Quarles back when it was at Second and Broad Street. The Hard Rock is there now.

“I started as a stock boy and ended up as shipping clerk. When I got off at Phillips & Quarles, I’d go down to the Harvey’s store at 9 o’clock and work until 1 in the morning, cleaning up.”

When he was at home, he’d go out to his garage and repair lawnmowers. Later he left the hardware company to work as head of housekeeping for the Gray-Dudley stove foundry on Clifton Avenue.

He fishes through his wallet to find a calling card for Royal Chef, a Gray-Dudley-founded janitorial service that also employed him in his “free time.”

And on weekends he’d often work on farms of friends out in the country.

All of that work helped him pay off this house long ago. He won’t disclose what the house cost him, but allows “it was real steep for back then.”

It’s no palace, no monument to ego. It’s a home, the place he and Addie have lived their lives. “We did have three bedrooms, but we took one over for a den. One bathroom and a kitchen, great big dining room, laundry room.

“We’re the only black family on this side of the street now,” he says. Oh, he could leave easily if he wanted to. “I got a letter the other day from some real estate company, offering $460,000, no closing costs, no fees. But I wasn’t interested.’’

Sure, that’s a lot of money, he says. But he’ll leave that fortune to his children, who he knows will sell the home once he and Addie are gone. “They won’t have any use for this house. They’ve all got houses of their own.”

He’s staying put, though. “At my age, why would I want to go live somewhere else? I got a comfortable home here.”

He is pleased by the demographic irony: “When we moved in, they started moving out. Now they are moving back in.” He’s just sitting here watching life’s merry-go-round.

“They are really building up this neighborhood. I don’t like people giving up their houses for the big things they are putting up. I like the houses they tore down much more than I like what they are building up.”

He leans back in the chair near the wall filled with photos of family, many of whom got their start in this house.

“I’m not going anywhere. No. No. No. No.,” says Alvin. “Not at my age. I’m not pulling up and going anywhere but the cemetery.”