VOL. 40 | NO. 20 | Friday, May 13, 2016

A life driven by his ‘disappeared’ brother

By Tim Ghianni

Fabian Bedne is a devoted, tireless Metro Council member and advocate for both his district and for Nashville’s Latino population, largely because a military death squad threw his blindfolded brother, Dario, from an airplane as “punishment” for being a Jew or perhaps because of his political views.

Fabian has no proof – a body never was found – but that was a most-common form of “execution” in the mid-1970s, during the reign of terror by the military junta that ended the Peron “dynasty.”

It was a time when good people “were disappeared,” says Fabian, 56, who in addition to spending his time with constituents both in his district and among the Hispanic population, is one of the partners in an architectural firm made up of four Latinos and one other Nashvillian.

“I’ve got three years left on my second Council term,” he says, sort of backing into this emotionally draining conversation while relaxing at his home in Cane Ridge, a community carved from parts of Brentwood, Antioch and surrounding land.

“Then I’ll have to take a term off because of term limits, so I may be done. I’ll be in my 60s when I could run again, and I don’t think I’ll want to. I’ve got a lot to do yet.”

Although supporters urge him to seek an at-large seat or run for the Legislature, “I don’t think I’ll do either.”

Driving him – in his work as District 31 councilman and as the voice of the city’s Hispanic population (“I’m the only Latino on the Council”) – is the spirit of Dario, his big brother and “hero.”

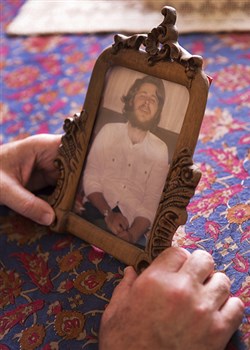

“He had a Rolex and a sports car and lived life. He was kind of a like a playboy,” Fabian says of the young man, frozen in time in a photograph in the hallway of the comfortable home.

“That was at a party at my parents’ house,” he says, pointing at the photo while shitzhus Kolby, 11, and Oscar, 9, make sure no one attacks his feet. “We rescued them from another family who couldn’t keep them anymore,” he says of his canine companions.

Dario somehow “was disappeared” while serving as a military draftee in Buenos Aires. “That was 40 years ago. He would be 60.” Fabian’s voice cracks slightly, but he fights away tears as he details how Dario’s murder “ruined the lives of my mom and dad, ruined my life, too. Whole family.”

He wills himself from the darkness by talking about how that brutal act stirred him to relish and protect the unique freedoms he found in 1990, when a professional scholarship brought him to America, part of a Council of International Programs effort that trains experts from around the world to battle societal ills or unfairness.

Fabian’s role was to help build affordable housing in Columbus, Ohio.

“That work was so rewarding,” he says. “All of what I do, I think, is because of Dario. My brother was one of 300 military draftees who were disappeared. Thirty thousand total people were disappeared. That’s the estimate.”

This devotee of the American liberties many (most?) take for granted told me a short, graphic version of Dario’s story nine years ago when he made his first (and unsuccessful) stab at the Council seat.

Huddled over coffee at a now-defunct Brentwood bookstore, I was there to write a tale about the uniqueness of this Hispanic politician’s campaign and background. During a long pause, his eyes glazed over and he talked, quickly, about Dario’s death and the inspiration he found in it to chase his destiny.

That part was “off the record” we agreed. The plan was to meet up again, when he would tell me the whole story, hoping I’d get it published in the city’s morning newspaper.

Fabian and I scheduled that meeting, but, a day or so before, he canceled. “I don’t want people thinking I’m using what happened to my brother to help myself in politics,” he said, emotionally asking me to forget we had spoken of the violent act that shaped his life.

Since it was not something people “needed” to know, and it had been related to me in confidence, I agreed to his request to “forget” the tragic tale, share it with no one.

Yes, it was a helluva story. But it was a matter of life and death and family to Fabian.

In addition to not wanting to “use” his brother’s tragedy, Fabian simply wasn’t yet emotionally equipped to unveil that tragic past. We agreed he would call me if he ever wanted to finally tell the story.

Nine years later, the phone rang. President Obama was in Argentina, where, among other state duties, he visited the memorial marking the mass grave created for the Jews and political dissidents who rained from the death squad airplane and into the Rio de la Plata. (The “River of Silver,” an estuary that drains into the Atlantic and is considered by some to be a bay, ranges from 1.2 miles wide at its source to 140 miles at its mouth.) The discarded bodies were retrieved by locals during that time of terror.

The president’s actions and words convinced this businessman and councilman it was time to tell Nashville his story.

“Obama sort of did what I hoped he would do,” says Fabian, in the thick accent of his heritage. “He did go to the monument by the river where they were thrown out of the planes … He threw a flower in the river. And he also said something along the lines that he was sorry … that the U.S. had not taken a strong role supporting human rights in the context of what happened.”

Throwing folks from planes even today remains a significant human rights violation.

“That was one of the favorite ways they did it with the dissidents in Argentina,” Fabian says, adding much has changed since he left his homeland 26 years ago for Ohio, where he met and married the love of his life, Mary-Linden, mother of Olivia, 18, and Gabriel Dario, 21. The family moved to Nashville two decades ago.

“When you write this, make sure people know I’m not talking about Argentina now. They have gotten rid of the draft, and the military has gotten professional. It’s a democracy.”

In 1976, though, a military of uniformed thugs ruled by intimidation. Fabian describes one bullying occurrence he experienced in the years after Dario forever vanished:

“One day I’m driving in my car, and a truck full of soldiers was getting in front of me. They kicked my car because I didn’t move fast enough. They pointed their guns at me, and then they drove off.”

Strange days, indeed, as he notes such events occurred all the time.

During those years, the American government looked the other way, as often has been the case when despots have been propped up as ways of keeping the peace and defeating communism.

Metro Council member Fabian Bedne holds onto a picture of his brother, who went missing from the military in Argentina in the mid 1970’s.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“The way our government (the U.S.) did it at the time was in a way that empowered the local military people to feel that they could do whatever they wanted without the international community doing anything to limit them. So in Argentina, the government was intent on domesticating people and limiting a political transformation that was happening at the time.

“As the French philosopher Foucault wrote: ‘The pathway to domesticate the minds is to domesticate the body.’”

He draws a long breath.

“The military would arrest you if you were wearing something they didn’t like. If you wore your hair long, they’d shave your head.” His mother cautioned her boys – “it was kind of in the hippie time”– to get their longish locks chopped.

“Immediately after the military took control, people started to hear of strange disappearances. People were picked up off the street and never to be seen again.”

But until it got personal, Fabian – teenage son of a successful Jewish merchant who owned a wholesale store – “was just getting on with my life” in an upper-middle-class Jewish enclave.

“My older brother (Dario) had been drafted into the military, and his superiors in the military gave him a bad time because he was Jewish. He would tell stories …. But you kind of get used to it when you grow up in an anti-Semitic environment.”

Back then, Argentina had a population of around 25 million, including 500,000 Jews. Some of the leaders burned with an anti-Semitic fever, perhaps imported when Hitler’s “boys” escaped to South America to avoid Nuremburg’s noose.

Fabian draws a long, deep breath.

“One day, I’ll never forget, I was at home. My dad calls me. He owned a store around the block. He said ‘you need to go look around for Dario. They called from the barracks and said he never made it. If he doesn’t show up, they will count him AWOL and they will punish him.’”

Fabian recalls installing his best detective mindset and dashing into the streets, asking people if they’d seen the Jewish neighborhood’s beloved playboy/military draftee.

“After a half-hour, I went back and told my dad that I couldn’t find him. My dad then went to the front of the barracks and saw a soldier that knew my brother from a Jewish club. My dad asked if he’d seen him. My brother’s friend said ‘I saw him earlier today when he came in.’

“My dad said ‘Well, that’s weird,’“ and he went into the military compound, where he was told Dario never did come in that day, and that if he didn’t come back soon he’d be court-martialed.

“That became the beginning of the time when my dad would be desperate to find out what happened to my brother.”

That desperation ruined the lives of Samuel “Mito” Bedne and his wife, Aida, and their other children, Fabian, Javier and Debora.

“My mom, every night for a year, she would get up and go into the bathroom and close the door and she would cry for hours. Like really cry. She didn’t want anybody to hear her. But we all did.”

Tears challenge his voice. Cry for me, Argentina….

A photo of Dario at his parents house in Argentina.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“It became more and more evident that my brother had been disappeared. So my parents were really scared. Usually when they do that, take one, they disappear a whole family. … The thing about disappearances is you don’t get your day in court. … Everyone was scared to death of the government.”

After a couple of days, Fabian’s dad, Samuel (nicknamed “Mito” after the doctor who treated his childhood polio) sued to force the government to prove what happened to Dario.

“He was told that if he didn’t remove the habeas corpus his whole family would be disappeared.”

Though Mito did as instructed. The fear never left.

“For many years I would be afraid … Looking over my shoulder,” Fabian says. “I didn’t tell my best friend that my brother was disappeared for about a year.”

Once friends found out, they shunned him and his family. They feared the military would come to their homes and “disappear” their family members with a Rio de la Plata sendoff.

“I began to think ‘what would happen to me if they do kidnap me? If they torture me, how am I going to deal with that?” Fabian says.

Many similarly oppressed, fearful Argentines fled to the U.S., our glorious refugee nation. Fabian’s parents wouldn’t budge.

“My mother didn’t want to leave the country. She would say ‘what happens if they release Dario and he comes home and we’re not here?’

“They never moved from that house for 20 years.

“They thought maybe he had been kept against his will. It was a fantasy. If you accept a person’s death, you kill him,” he adds, trying to describe what motivated his parents’ stubbornness.

Fabian discovered his activist future when he encountered a progressive Jewish newspaper that was urging people to march against the Argentine government.

“If you have ever marched in that context … with hundreds of police officers with long sticks and horses, ready to beat the crap out of you and you do it anyway, if you can survive it, you know you can do it because it’s the right thing to do.” What a field day for the heat.

“It changes your character,” says Fabian.

“So when I stand up for things today, things I believe, important things for people, human rights, I can do it because I was able to do that,” says the Metro councilman and Latino leader.

“What happened to my older brother happened 40 years ago, but it drives my conversation all the time, even now,” he says. “It was like the end of innocence.”

After the reign of terror ended, Fabian decided “it was time to take a sabbatical” because the new president gave the military amnesty, meaning there could never be justice for Dario.

So the young architect and assistant professor – “I always really liked teaching and trying to communicate with the students and help them to see the beauty of the design” – applied for the program that took him to Ohio.

His work there was done after six years, about the same time his wife’s father – “I really loved Ernie” – was stricken with Alzheimer’s.

They moved to Nashville to seek new careers and care for him.

Fabian decided to run for Council a decade later, hoping to use lessons learned in Argentina while toiling for human rights in the land of the free, home of the brave.

“The thing I always get asked is ‘Why did you run for office?’ It’s very hard for people to understand unless they know how I grew up,” he says. “When you see how overpowering and overbearing government can be without any checks and balances on what they do, it’s overwhelming.”

He also was overwhelmed by his discovery of how different life is in America.

“Part of my passion and love for this country is the fact that people feel so free to have an opinion and to exercise whatever their dream, without feeling they will be tortured or killed or subject to any punishment by the government.

“I like the fact that people can live their lives here without realizing how lucky they are. It’s a sign that as a country we’ve done a good job of making people feel safe.”

As a Metro Councilman, he deals with those people on the most human, street-level problems.

“We can’t end the Iraq war,” he explains. “But if there is a problem with a sidewalk or with the police, we can do something.

“I am very empowered by this.”

Mito and Aida both died within the last five years, never knowing what happened to Dario, whose spirit thrives as Fabian’s motivation.