VOL. 39 | NO. 30 | Friday, July 24, 2015

Rekindling the flame that was Jefferson Street

Lorenzo Washington tries his hands at playing the piano donated to his studio by Jackie Smith, the daughter of Nashville’s legendary W.O. Smith.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerLorenzo Washington pushes “pause” on his conversation so he doesn’t have to compete with the scream of a fire engine as it roars past his Jefferson Street recording empire and into the barbecue-flavored haze of this steamy, storm-threatened mid-summer’s day.

Sirens join bass speakers booming from vehicles as the soundtrack of this once-great, now somewhat-decrepit avenue through historically black North Nashville.

This day is noisier than most as a violent storm shakes trees from the sky and causes widespread damage and power outages short miles from where Lorenzo and I stand in front of Jefferson Street Sound and look southward, toward swirling, dark clouds carrying rain that washes what might be called the “historically white” part of Nashville. Green Hills and Oak Hill are particularly hard-hit on this day.

“This is the only street African-Americans can claim in this whole city,” says Lorenzo, 72, leaning on the outside wall of the rehearsal hall, inside of which a drummer gives his sticks and kit a workout while prepping for the arrival of the rest of Markey Blues Band.

Jefferson Street Sound – the words on the shingle hanging outside the multiple-locked, humble building – houses the rehearsal space, a recording studio and Lorenzo’s Clean Tech Cleaning Service HQ, as well as his apartment and a miniature museum of artifacts and memorabilia from North Nashville’s musical glory days.

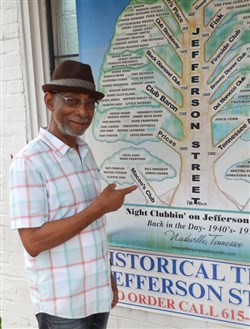

“Clubs all up and down here,” adds Lorenzo, pointing toward a poster on the front of the complex that shows the family tree of nightclubs, restaurants and great performers that gave this stretch its long-vanished neon-lit luster. “My friend, Dr. Morgan Hines, a dentist, did the graphics on that tree,” he says proudly.

“Night Clubbin’ on HISTORICAL Jefferson Street” reads the bold print below that tree. Names of clubs – Del Morocco, Club Baron, Stealaway and more – serve as branches. The tree’s foliage is filled by names like Joe Tex, Memphis Slim, James Brown, Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and Ray Charles, a few of the stars who lit the nights and early mornings during the street’s golden age.

“That was back in the day,” says Lorenzo, explaining how the music flowed freely from the 1940s and into the 1970s.

From the front of Lorenzo’s 3,000-square-foot building at 2004 Jefferson Street, you can look down the once mighty avenue toward the overpass of Interstate 40, which decades ago cut North Nashville in two, effectively murdering the graceful neighborhood where black residents – from educators to merchants to club owners – lived and thrived, sang and danced.

Or even played guitars with their teeth, in at least one notable case.

That I-40 killed the spirit of this neighborhood and its nationally recognized R&B scene is well known.

The “Night Train to Nashville” exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum (and accompanying Grammy-winning album) a decade or so ago highlighted this strip’s heritage before bulldozers and wrecking balls replaced homes and night clubs and suffocated the spirit of “oneness” that made this such a black paradise.

That I-40 overpass, for example, forced the demolition of the legendary Del Morocco – a regular haunt of Jimmy (later “Jimi”) Hendrix, Billy Cox and Ironing Board Sam.

Nearby, tractor-trailer exhaust haze obscures the spot where the inspiration for Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” was born: a little pad, illuminated by a single hanging light bulb, that Jimmy (not yet “Jimi”) and Fort Campbell Army pal and bass wiz Cox rented inside a long-ago demolished beauty college.

“I met both my wives here on Jefferson Street,” recalls Lorenzo, tilting back the brim of his pork pie. “Hats are my thing,” he unnecessarily proclaims as he stands in the 100-plus-degree heat and humidity outside his building.

Feet away, Oohwee Barbecue belches pork-flavored smoke from the mobile home-turned-diner that once housed Mahalia Jackson’s, the restaurant from which North Nashville’s legendary chicken and fried-pie king, E.W. Mayo, long-ago hoped a national franchise would spring. Dreams die hard on Jefferson.

The fact the barbecue joint has brought sweet-smoked life to the long-abandoned site of Mayo’s dream is a sign something is happening on the street that once was known nationally and internationally for its club and restaurant scene.

“It’s beginning,” Lorenzo says. “First thing they are doing is (developing) down by the new baseball park (at the far end of Jefferson). Then they’ll begin bringing more condos down this way. And with the condos will come more people. And those people will need places to eat, places to hear music. It will happen. It is happening.”

He notes that just a block away, black and white middle class families move into new homes or those rescued from the neglect that rotted North Nashville’s spirit.

In addition, Nashville announced this spring it would relocate police headquarters to Jefferson Street. The proposal was met with pushback after some in the community members felt blindsided by the announcement. Mayor Karl Dean has since delayed the plan in order to have more community meetings.

“My goal is to establish Jefferson Street as a prominent-like business district again,” Lorenzo notes, adding he draws inspiration for his pursuit from his many musical friends, like Jesse Boyce, a former Motown and Little Richard bassist, and other Jefferson Street boosters, like the neighborhood’s junior football league that used his parking lot for a summer picnic last weekend.

“Spent all morning weed-eating and cleaning up for them,” he says. “They had fun.”

This street – often ignored by the white majority and gunshot-fearing folks of all shades – is a trail of history and hope for Lorenzo, who moved into this building five years ago to contribute to the revival of the area’s musical and human soul.

“People are beginning to take notice of what’s happening here,” explains Lorenzo, hastily adding folks shouldn’t be so wary of violence here. As urban renewal has begun to flourish, at least down by the ballpark and near Rosa Parks, gang-members are finding it more difficult to afford escalating rent.

“I hear a lot of them have moved on out to Antioch,” he says of the gangsters. He’s not slamming Antioch at all, he says, but is saying this street, where glistening rims spin, catching the sun as cars hip-hop past, is changing.

And, if it works out right, the historic highway that sprung one of the NFL’s first black quarterbacks – the ill-fated but engaging young fellow named “Jefferson Street Joe” Gilliam, a short-lived Steelers star from Tennessee State, gentle “Joey” who lost his battle with street evils – will again become a place where memories are made rather than simply recalled from tattered lawn chairs.

Coffee Jones and Lorenzo Washington have been using the old WLAC-board once manned by legendary R&B booster deejay John R. (John Richbourg) to recreate the sounds of Jefferson Street.

-- Tim Ghianni | The Ledger“Now Jefferson Street, as we knew it, we won’t have it (back) without work,” admits Lorenzo. “We got to do something as a race that’s going to continue to have people recognize Jefferson Street as OUR STREET.

“You wouldn’t believe how many black millionaires there are in Nashville. If you are going to invest your money, North Nashville is one of the places to be putting it right now.” (And yes, white millionaires and – when the time comes – club patrons are more than welcome to participate.)

Blocks to the east, the new Sounds stadium has drawn even more condo and retail development to gentrifying Germantown and Farmers Market areas.

Young African-American entrepreneurs (as well as their white counterparts) are investing in new businesses.

“There’s a shoe store over there on 11th and Buchanan,” Lorenzo says. “I’m going to go there and get me some new shoes.”

More new retail will join that store, he says, noting that developers have bought three or four buildings, including the old dry cleaners, also at 11th and Buchanan.

It seems Ed’s Fish, at 18th and Buchanan – one of the few thriving survivors of North Nashville’s bygone glory – soon won’t be so lonesome.

With that increased speculation, property values (and rent) have increased. “It’s hard for me to afford to be here,” Lorenzo notes. “That’s why I don’t have an Audi or a Jaguar parked out front. I’ve just got that old station wagon.”

He later admits the gray 2003 Chrysler Town and Country van, with its sound system, leather interior and space for hauling cleaning materials, day-laborers, instruments and musicians, is a fine ride.

While he runs his recording business and miniature museum by day, the evenings and weekends are devoted to luxury auto dealerships from here to Franklin, businesses which for decades have counted on Lorenzo’s Clean Tech janitorial operation – where two of his brothers also work – to freshen up their buildings for the next day’s customers.

“I work every night until about 11, then come home and get some sleep here. Then I come into the (Jefferson Street Sound) office at about 9,” Lorenzo says.

His entrepreneurship, his dreams, his fearless labor and his devotion to revitalizing the city’s soul, were birthed “in the projects” of East Nashville, he says.

“Eighty-nine Wichita Street,” he remembers. “I’ll never forget that one. We didn’t have no running water in the house. No electricity. We had coal-oil lamps and the toilet was about, shit, 75 feet from the house in the back.

“We had a pretty rough time, but it didn’t seem like such a rough time at the time. My father never was with us,” he says. Mother Julia provided for her family by working at night, cleaning the Stahlman Building, then one of Nashville’s lonely skyscrapers.

“To have a job in that building was a real blessing,” explains Lorenzo, who even as a 7-year-old tagged along to help as mom scrubbed and polished floors, toilets and ash trays.

Lorenzo and his two living siblings, James and Ernest, picked up their passion for cleaning – their main livelihood – from those nights with Julia. (Another brother, Thomas, died in a 1970s wreck in North Carolina, where he’d gone to transport cars back to Tune Import Motors in Nashville.)

Lorenzo Washington keeps the Jefferson Street historic music scene “tree of life” on the front of his studio.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerWhile Clean Tech’s customers include “the Audi dealership, the Porsche dealership, the Range Rover and Jaguar,” there are non-vehicular customers.

“I’ve also got an architect firm and a law firm.”

Lorenzo supplements the mostly family workforce at the Rescue Mission. “Whenever I’ve had big jobs during the last 27 years, I’ve used a lot of people from the Rescue Mission. I go and get those guys and put them to work.

“That’s been one of my ministries. That is something God has given me to do is to work with some of these guys who are less privileged than myself. I’ve got a great relationship with the guys from the Rescue Mission.”

That he cracks a bright smile isn’t unusual. “I’ve lived in Nashville all my life and I’ve had all kind of businesses. I had the Soul Shack Record Shop back in the ’70s” on Buena Vista Pike in North Nashville.

“And a barbecue: Lorenzo’s Black and White Pig Pit Barbecue. I put the white in there because I didn’t want to leave the white people out,” he says.

Actually, he went into the record business because the Washington brothers, while great at cleaning, didn’t have the natural-born passion for barbecuing. And good help was hard to find.

“(The barbecue chef at the Black and White Pig) was passionate about the barbecue business. He was an alcoholic, too. Me and my brother ended up doing all the cooking because he’d come in half-lit.”

While Lorenzo learned how to hold his own with partial pigs at the corner of 15th and Buchanan, he knew he was ill fit.

“I only did that for three years. I decided I wanted to go in the record business instead. It is all about selling units and I thought I could sell more units from the record store than from the barbecue business.”

Twelve-inch LPs of all blues and jazz categories, remnants of that old store, line the walls and fill a closet inside his miniature museum to the musical soul of Jefferson Street. In addition to a wall of fame, a stunning portrait of Miles Davis – you can almost hear “Kind of Blue” and “Bitches Brew” – presides over the museum.

Lorenzo’s not just collecting urban music relics: He’s making it in the upstairs studio, flavoring it with the history of the street where he chases his dreams.

Producer and bass guitarist Don Adams’s “Caution May Cause Passion” jazz and R&B collection was the first album recorded by Lorenzo. He also insists it was the first album ever recorded on Jefferson Street, since “back in the day” there were no studios here.

On this day, Coffee Jones, a Christian hip-hop and R&B performer with the group Grits, is in the studio, where he is most days, helping Lorenzo perfect a musical style that rejuvenates that which made Jefferson Street famous.

“We are working on a ‘Jefferson Street sound,’” Coffee says, after spending a part of the day at the production board donated to Lorenzo that once belonged to WLAC’s “race music” champion, deejay John R. (John Richbourg).

Coffee and the rest of those participating in this recording aren’t copying the sounds of Bobby Hebb, Marion James, Frank Howard & The Commanders, Jimmy Church or emulating the genius of Johnny Jones (the undisputed winner of a legendary guitar duel against a pre-experienced Hendrix, at least according to the countless masses of people who claim to have witnessed it in the Club Baron, a building now occupied by the Elks.)

Coffee and Lorenzo are trying to bring that old music back by adding modern textures.

“It’s more of a reminder of what has evolved out of here,” Coffee says. “Jefferson Street has been a part of Music City long before country became the iconic music of Nashville.

“I think it’s important for people to know what happened here.”

Lorenzo, who is counting on a No. 1 hit to pay off his business risks, mentions that if Motown magic could be birthed in Berry Gordy’s little house in Detroit, there’s no reason his Jefferson Street Sound can’t produce something equally breathtaking.

“I don’t know of no one else in town that’s still trying to keep the legacy of Jefferson Street going,” he says, eyes following the rush hour traffic bumping and grinding past the 3,000-square-foot building that houses his “field of dreams.”

Sure it’s a building, not a cornfield, but it’s Lorenzo’s “if you build it, they will come” paradise, from which the music produced will bring back the musical ghosts of Jefferson Street while contributing to his street’s revival.

“You won’t recognize this place in three years,” he promises. Nightclubs, restaurants and tourists of all shades will revive this historic street with its R&B heartbeat.

“I want to be a part of keeping the legacy of Jefferson Street alive.”