VOL. 38 | NO. 43 | Friday, October 24, 2014

Embracing immigrants with open arms

By Hollie Deese | Correspondent

Immigrants have warmly embraced Nashville, and increasingly, the city is warming up to them, welcoming a broad international community to add to the city’s burgeoning success.

“Immigration is obviously a sensitive issue and people get passionate about it, but I think Nashville has benefited a great deal from the fact that it’s become more diverse, benefitted a great deal from the influx of new immigrants, and I think that our rise to prominence and our increased prosperity, is actually linked to that,’’ says Mayor Karl Dean, who recently created the Mayor’s Office for New Americans [MONA].

“I think we’re proud, we want this city to remain what it is, a welcoming and opening city.’’

“It is a fascinating journey the city is on at the moment,” says Nashville native and longtime civil rights activist Iris Buhl.

According to the mayor’s office, the number of foreign-born residents in Nashville has more than doubled over the past decade, and in 2012 Nashville had the fastest-growing immigrant population of any American city.

Today, 12 percent of Nashville’s population was born outside of the United States, and nearly half of those people are recent immigrants who entered the country since 2000.

“When we arrived 18 years ago it would have been great if there was a Center for New Americans,” explains South African immigrant Kobie Pretorius.

“Nashville back then is not the Nashville, we have now, and if you were an immigrant in the 90s, you definitely stood out. With my husband being at Vanderbilt, there were some international folks, but living out in the neighborhoods, it was a rare thing to run into an immigrant here and there.

“So now it is nice – it is starting to feel more like a rainbow nation.”

Pretorius is optimistic that MONA will continue to lessen the racism that immigrants face, although a recent hateful and racist-filled comment thread online connected to a Tennessean article about a bilingual sign that went up at Casa Azafran, Conexión Americas’ multicultural hub, leaves her a bit heartbroken.

This photo of Gatluak Thach, 18 years old, right, and his brother Wiyual Ter Thach, 14, was taken before they left South Sudan for America. Thach has written about his American dream.

-- Submitted “I think it has great potential not only to make new - and old - immigrants feel welcome, but also to help us better integrate into the Nashville community,” she says. “I believe we also have a responsibility as hard-working immigrants contributing economically and culturally to the growth of Middle Tennessee, to change the hearts and minds of Tennesseans about the negative perception they often have about immigrants in our area.”

Here are some of the stories in Nashville’s history of acceptance.

Walking to work, going to church

“I came not knowing the English language and I just celebrated my doctoral program,” says Gatluak Ter Thach, founder and CEO of Nashville International Center for Empowerment, a nonprofit community-based organization that provides direct social services and educational programs for refugees and immigrants in Middle Tennessee.

“The support I received from the community has been extraordinary, from the public and private sector, from individuals and families, it is just unbelievable. There are only a few things I can say wrong about Nashville, and many things I can say right.”

It’s was unstable path Thach himself walked when he first moved to Nashville from South Sudan in 1996. He had no family here, except for the 14-year-old brother he cared for.

“I came here after I knew there was a group of people from my community in Nashville,” he recalls. “I wanted to come here because I heard I could find a job even though I could not speak English. I was told the people in Nashville were so friendly, and there were many churches in Nashville. I came from a Christian family, so there would be a place to attend church and even a place to attend church in my own language. Those were reasons that brought me here.”

Thach’s first job, as it has been for many immigrants and refugees, was working at the Opryland Hotel as a dishwasher. Sometimes he would walk from East Nashville to downtown, then from downtown to Murfreesboro Road to catch a ride to the hotel, and then do it in reverse on the way back.

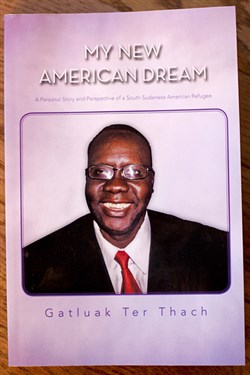

Gatluak Thach wrote this book about his American dream.

“There was no transportation to take me from the hotel to East Nashville, so I would walk from on foot,” he adds. “At the time I didn’t like that – it would be cold and chilly and you would also be scared because you never really know what is going to happen to you while walking.”

Today, Thach serves on several leadership boards of directors, including the Sudanese Human Rights Organization, Tennessee Immigrants and Refugee Rights Coalition, and the advisory council for Nashville’s mayor on refugees and immigrants, and Tennessee for All of Us. He is also an author of “My New American Dream.”

Still, transportation, child care, housing, work and health care are all needs immigrants struggle to meet when they first arrive in Nashville, and community groups help them connect to the services they need.

“When people do not speak the language, when they are not finding jobs, not finding reasonable services they need – child care, transportation, legal services - they do not know where to go,” Thach notes. “And by the number of people we serve in a single day, there are a lot of people not yet integrated into society, but want to be a part of society. It is an on-going process but also a process that is meaningful.”

“Refugees and immigrants, new Americans, when they come to Nashville they want to integrate into society, and they want access to services so that they will be able to support themselves,” explains Thach.

Many times, helping them learn English is the first thing step – without breaking the language barrier – integration can be next to impossible. Thach says they have helped people from 70 different nations, including Iraq, Somalia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Cuba and increasingly, most recently, Bhutan and Burma.

“The concern varies, but for refugees who have lived somewhere in Africa in a refugee camp, when they get here they think America will do away with every problem they have,” he says.

“When they get here, nothing is gone away with, and they don’t know where to go. They need to find a job but they don’t have transportation. They need to leave their children somewhere to go attend English classes but they do not have child care support. They need to find a better job but they don’t know where to go to find that better job. They need to find a community in which they belong but there is not a lot of people in their community here.”

Raising ‘little Southerners’

In Pretorius’ wildest dreams she couldn’t have imagined raising children who spoke with a southern accent - at least not southern American. When she and her husband Mias, both 44, moved to Nashville from South Africa in 1996, they were newlywed students starting an adventurous new life. Now they have two tweens who are Native Nashvillians growing up in West Meade.

“They are little southerners,” she jokes of Mia, 13, and Stefan, 11. “They have a little twang, and my family can’t understand a word that comes out of their mouths. They have to repeat everything a few times.”

Of course, her children’s assimilation into Middle Tennessee, much less America, was a much easier process than her 15-year journey from arrival to attaining her citizenship in 2011. After all, they were born here. But Pretorius has had to jump through some seriously daunting hoops.

Her husband applied for a residency at Vanderbilt, which required several exams. The South African government at first denied their visas, striving to keep doctors at home. He finally attained a J-1 visa so they could study in America for four years. She was only granted a J-2 visa as his dependent, which restricted her work and forced her to reapply every year.

The VA hospital ended up sponsoring them for a green card, but after 9/11 their paperwork slowed to a crawl. They were eventually issued green cards, and then had to wait five years to become citizens, which they did in 2011.

“It is daunting and a long process and definitely not easy,” she says,

The “new Nashville’

Buhl, 71, has seen the city grow and evolve through civil rights activism, race relations and a growing immigrant community. She has been involved in it all over the years including her time as a research assistant for Susan Gray and her work on early education in the inner cities in the 60s, her involvement in the gay community, as development director for Nashville Cares, Brooks Fund and Community Foundation, the Family of Abraham – this list goes on and on.

“I have seen a change or two,” she adds. “When people are mistreated for no good reason I can figure out, I just tend to gravitate in that direction.”

Her current work with Community Nashville includes outreach and advocacy work with a focus of human rights. In May, they award community leaders who make Nashville a better place by working to eradicate bigotry.

“What we have tried to do is capture the old and the new because obviously race relations continue to be very important,” she says. “But we are trying to look at the new Nashville, the 21st century Nashville, and recognize those people who are doing very important work in the area of human relations across the board.”

Dean’s new Metro Government office focuses on engaging and empowering immigrants living in Nashville to participate in their local government and communities. Buhl thinks it’s another great step in Nashville’s history of acceptance.

“It appears to me the mayor’s office is looking at a lot of dimensions to this, including the one the Chamber has taken on which is the economic importance of the area of having all of these folks, so many of whom are entrepreneurial, and giving them a platform and support to do their thing in order to enrich the community,” Buhl says.

Additional goals of the office include fostering a knowledgeable, safe, and connected community; expanding economic and educational opportunities for New Americans; and working with community organizations and other Metro departments to empower and support New Americans.

“This is incredible for Nashville,” explains Thach, a member of the Mayor’s New Americans Advisory Council.

“It shows we are embracing diversity, embracing the new groups who are coming. This means the communication will be much easier because the Mayor’s office needs to know what is going on in the community. They need to have the connection, and they need to receive the information that is needed. I think it will support job creation, and it will also support integration into the community.”

Entrepreneurship and job creation

Thach says he is hopeful MONA will allow for more job creation in Tennessee and Nashville for immigrants, which will also make it easier for the integration into the community. But he wants there to be more focus on assisting immigrants who want to create their own jobs too.

“We assist those who came with a career back home that is not translated into this system,” he explains. “We want to make sure they are connected to the services that will help them and certify them so they can use these life skills that they have. But it is so challenging now.

“Immigrants are very wonderful innovators. They love to be entrepreneurs, but at the same time you can’t be an entrepreneur when you don’t really know where to start. You have to be connected to the resources in order to know what to do.”

Pretorius may have had a leg up on other immigrants in finding work thanks to speaking English, but her hard-earned degree was useless in Nashville.

“We learn English from a young age so we don’t have the language as a barrier,” she says. “What is hard is that our degrees don’t get recognized here. So a lot of women come here with bachelor’s degrees, but people are like, ‘Meh, you have to go back to school.’ But in a lot of instances you don’t have the money, you have children. So that is a problem, and you basically start from scratch at an entry level job when you are at a higher level already.”

Aside from that barrier, many women from South Africa who come with their husbands just aren’t allowed to work at all because of the limited dependent visa they are issued. It’s one of the reasons she started the group Friends of South Africa a decade ago.

“It’s a problem,” she explains, of stripping women of their ability to work. “So they are here, they are lonely, and they need a place for support. So we get together once a month, and we have tea and we just talk about all sorts of things. It is fun to know you can speak Afrikaans, and we make our own little goodies. My goal is to have people arrive and for them to feel welcome, but also to integrate and become party of the society.”

Battling isolation

Community groups make the transition easier for many immigrants, but they can be so comforting and familiar it can be difficult to want to break away. In fact, it is that delicate balance of assimilation and retaining culture that most immigrants struggle with that could be one of their greatest challenges.

South African Kobie Pretorius with her husband Mias, daughter Mia, 13, and son Stefan Pretorius ,11), pose with a South African flag in their West Meade home.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“You happen to be in a place where you do not have any relatives, you do not have any friends, the network you might have had is not there, the language is a barrier,” Thach explains. “That is a lot [to cope with], especially if you arrive with nothing. Finding community is so important because immigrants love to be involved in their community. They love to have something to belong to them, to identify themselves with. When they don’t have that they kind of feel, one part of them is not there.”

Pretorius agrees how hard it can be to leave the old life behind, and that is why groups are so important. But it is important not to solely depend on them when building a life in Nashville.

“When you are new, your head and your heart is still so much in your old country,” she adds.

“You are reading the news from there, that is all you want to hear about, and you don’t become involved here. I think the mayor’s initiative is a great thing to make people step out of their little group of people you feel comfortable with and become active in their communities, to have a voice. I think all immigrant groups have a lot to contribute to be heard. We are proud of our South African roots, but we love living and contributing to the community here in Middle Tennessee. We eat dried meat made from beef called "biltong,'' not jerky, watch rugby not football, we say howzit, not what’s up. We are different but we are also similar.”

Parents struggle, teens excel

Going to school every day makes staying a cultural bubble nearly impossible, so kids and teenagers almost automatically assimilate by default. And it can cause some serious turmoil at home.

“Being a new area, a new culture with a new language, there is a role change within the family,” Thach explains. “There are intergenerational issues and gaps because kids will adjust so quick to the life, and the parents are left behind and probably see the world different. And sometimes the parents want the kids to have to live and work and act like them, when culturally they are different.”

Teenagers seem to assimilate the best, but are almost always more acutely aware of what other people think.

“One of the biggest things I have observed over the years in the Cambodian communities, and certainly the Hispanic and Muslim communities, is the parents really, really struggle with the place of their children, who of course being teenagers want to break away anyway,” Buhl says.

“They are really concerned they are going to lose touch with their cultures. And sometimes the kids do. Sometimes they get caught up in things that are not always the best – not all of them – but it is a constant concern about how to keep the kids in the fold, yet have them do well. It’s a real conflict for so many families.”

Community Nashville’s Building Bridges program works with area youth, helping them face their own feelings as they learn about the root causes of prejudice, become more understanding and learn to respect others. A weeklong summer camp brings kids of all nationalities together to interact in an honest way they might not get otherwise.

“What the kids learn and what they do when they get together is share what they feel are the important aspects of their culture,” Buhl adds. “I was visiting one night a couple of years ago at the camp, and they did an activity where the kids would come up with things they saw that united them, the common thread, and how they felt the rest of the greater community saw them.

“They would all share the closeness of family, and yet, they were acutely aware of the stereotypes they felt the rest of the community had about them. It’s tough.”

Thach and Pretorius hope the community can see that new Americans really want to be here – they would not go through the trials if they didn’t. But they need reciprocation from Nashville as well. No one wants to be the person in the relationship who puts in all the effort.

“New Americans who are here, they love to be here,” Thach says. “They want to be here. They came here because they want to be successful. They want their children to be more successful. “They came here because they want to better themselves. They want to be a part of the community that allows them to be part of it. They want integration to be two-way, whereby I will come with who I am and what I have and hold on to some of the things from my original knowledge and background – while at the same time – integrate into a society so that I feel part of it.”

Sheila Burke contributed to this report.