VOL. 38 | NO. 12 | Friday, March 21, 2014

Real people, real need for medical marijuana

By Hollie Deese

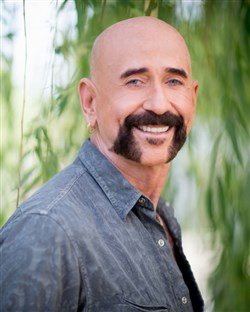

Hinson

Patient advocates who are pulling for the passage of medical marijuana legislation and regulation in Tennessee want others to know that they aren’t a bunch of hippies looking for a buzz.

For them, cannabis is a true lifeline.

Jimbeau Hinson, 62

Singer and Grammy-nominated songwriter

HIV/AIDS survivor

When Nashville artist Jimbeau Hinson, 62, was first screened positive for HIV in June 1985, there was not much known about the disease other than it was killing young, gay men across the country. The blood test for screening had just been approved that year, and it was still a few months before actor Rock Hudson died from AIDS, putting a familiar face on a totally unfamiliar disease.

“It was a hard time,” Hinson says. “It wasn’t even called HIV then. I was having some strep infections, and my doctor suggested we run this new test. I was running six miles a day and going to the gym five days a week. I was in tip-top physical shape when they told me I had six months to two years to live. And the emotional toll of that was the first thing that was hard to deal with. I couldn’t imagine being 175 pounds of solid muscle and being dead in six months –1985-1996 was just terrible.”

Hinson has been openly bisexual since the early 1970s, but has been monogamous with his wife Brenda since the disease was first reported to be sexually transmitted in 1983.

He kept his HIV diagnosis a secret between him and Brenda until 1996 when he slipped into a coma from full-blown AIDS. His organs had shut down, his blood had stopped clotting, and he had a fatal infection in one of his heart valves.

Hinson hallucinated dead people piling up in his hospital room, a morbid welcoming committee that imparted thoughts of love for him so he could pass over.

“It wasn’t frightening – it was peaceful in a sense,” he says. “And in the company of my deceased father, I crossed over and melted back into one with God again. It was the most inclusive, peaceful, mystical thing I have ever experienced.”

But that wasn’t the end for Hinson, who for no medical reason woke up tied down to a bed in the ICU. He weighed 110 pounds. The fact he came back from such dire circumstances changed Hinson’s perspective on his diagnoses though, and he found the will to fight his disease publicly.

“It took away all of my fear,” he says. “It took away all of my anger. I had been dealing with rage and fear ever since I was tested. I had never been an unhappy person, and I had never been an angry person, so it was hard. But thanks to the love of my wonderful wife who has stuck with me through it all, I am undetectable and healthy again.”

Hinson says medical marijuana gave him the mental strength to cope with the rage over his diagnosis and depression about the AIDS tragedy in general. Cannabis also gave him the ability to eat enough to keep his strength up, and in the meantime, HIV medicines improved over the years.

“Marijuana was a huge help in allowing me to cope with the mental agony of what I went through,” he says.

Hinson had been on the Vanderbilt experimental program in the ’80s, as soon as such programs were available. He tested every drug that came out, some of which had side effects like manic depression.

“I actually built a garage to kill myself in,” he says. “I was wasting away. I couldn’t keep food down. I had ulcers from these medications that would not allow me to eat. With marijuana I was able to force feed myself crumbs from a boiled egg and sips from an Ensure can to keep me alive. It absolutely kept me alive until the medicines got better.”

He was at his lowest with AIDS in 1995, preparing to die when the first protease inhibitor came out in early 1996. He began to rebound, but crashed hard, which is what put him in his coma. He and Brenda assume it was due to all the toxic drugs he had been on for so long aggravated by a small error by his pharmacy on one of his preventative antibiotics.

After an eight-week hospital stay, in which he recovered from his coma, he got back on the protease inhibitor cocktail regimen and slowly built himself back up.

Today, Hinson is healthy and his HIV is undetectable. His debut album, Strong Medicine, chronicles his journey, which he has taken with his wife of 33 years. He has seen society’s mindset change in terms of accepting people in the LGBT community, and wants to see the mindset about medical marijuana change as well.

“It should have been legalized a long time ago,” he says. “Everyone knows someone who has cancer. Everyone knows a child with terrible health problems. And most everyone in my generation has at least smoked it. Hell, even Obama has smoked it and admitted it. Bill said he didn’t inhale, but we know he did. Legalize, regulate and tax. It’s pretty simple.”

Hinson and his wife do not support recreational use of pot by young people.

Jamie Givens, 51

Licensed massage therapist

Breast cancer patient undergoing radiation

After Jamie Givens, 51, was diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer last summer, she has done everything to save her life that her doctors at Vanderbilt University Medical Center have suggested.

She went through chemotherapy, and gets infusions of antibodies. She had surgery in January to remove the cancer that had spread to her lymph nodes, and the tumor in her breast that had receded.

Givens is technically cancer free now, but this week she started an aggressive follow-up round of radiation treatment, five days a week for six and a half weeks.

“Inflammatory breast cancer is different from a lot of other breast cancers,” she says. “It’s painful, it’s hot. It grew very fast and my breast changed daily. Once I started chemo, my oncologist told me they were throwing everything at me.”

The treatment has been hard on Givens, striking her with extreme nausea so unlike anything she had ever experienced before that she would spontaneously tear up. The doctors had her on four anti-nausea medications, but nothing helped.

“Sometimes when I had a nausea spell with the chemo - and I still get days like this – I knew if my eyes welled up with tears it was going to be a bad one,” she says. “It would just be so intense, even with the Zofran and Phenergan and anti-nausea patch and anti-anxiety medicine with anti-nausea, sometimes it took medical cannabis for the nausea to actually dissipate.”

Givens says friends and family unfamiliar with how medical cannabis can cause relief would be amazed when they could see her suffering gone within minutes of inhaling. “They couldn’t believe their eyes that it could happen so quickly,” she explains.

Givens is ready for the legislature to approve medical marijuana, as long as the bill is not amended to omit parts and pieces of the plant, for example making oil and lotion use OK, not vapors or smoke.

“In radiation I am going to lose the bottom part of my right lung so it concerns me that the amendments being attached to Koozer-Kuhn [also known as House Bill 1385 or the Koozer-Kuhn Medical Cannabis Act] exclude the majority of people who need the medicine,” she says. “We are just hoping for some safe access across the board, not just oil.”

Givens also worries that she could lose her license to practice massage therapy because of her use of medical marijuana, but says the cause is too important to keep quiet about.

“The states in the south are changing their attitude and it is not a goofy thing anymore,” she says. Part of the problem is that every time there is a medical marijuana story they show hippies and young people smoking pot or big jars of buds from a dispensary in another state. They don’t show the MS patients in walkers.”

Millie Mattison, 2

Family moved to Colorado from Nashville for access to medical cannabis

Nashvillian Nicole Mattison and her husband, Penn, had always tried to live a natural life. Their first two children, Neal, 10, and Sam, 7, were both born at home, and they expected their experience with Millie, 2, to be similar. But nothing about Millie was what her parents expected.

“At birth, they were concerned,” Nicole says. “She has microcephaly, where her head circumference is just a little smaller than the normal size. She had some difficulty with sucking and swallowing so she stayed at the hospital for a few days, and I worked with her to make sure she was taking in the ounces they felt comfortable with. We had a genetic follow-up for 6 or 9 months later, and we thought it was just a little thing, nothing to worry about.”

Millie Mattison with her mother, Nicole

Within a month however, Millie had lost a lot of weight and was acting differently than the other two babies had. They went to their pediatrician for a follow-up, but soon she was turning blue at the Vanderbilt ER. A monitor showed she was refluxing and would stop breathing when she did. She had a surgical procedure that wrapped her stomach around the esophagus, and a gastrostomy tube was placed to stop the reflux.

Mille’s condition went from bad to much worse. Two weeks after the surgery, she began to have epileptic seizures, and the Mattisons found themselves immersed in tests, transfusions, scans, medications and multiple stints at the hospital.

“We were very scared,” Nicole adds. “As it went on and nothing was helping, and all of her genetic testing was coming back normal. That is when we said ‘Hey, we did great with our first kids doing what we felt was best. Why aren’t we doing that with Millie?’”

At the recommendation of Millie’s neurologist at the Neurometabolic Clinic at the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, they switched the baby from a soy ketone diet to a natural one, and in one month, Millie gained three pounds and grew a few inches. But the family was in and out of the hospital, seemingly going two steps back for every step forward.

In April 2013 Penn watched the Dr. Sanjay Gupta documentary ‘Weed,’’ and the couple began to seriously think about what medical cannabis could do for their daughter. When Millie’s doctors approached the couple and suggested they consider hospice care after a particularly bad episode, their minds were made up.

“It came to a head one day when in we came for a hematology follow-up, and she was at the lowest she had been,” Nicole says. “The kidney doctor admitted us to do more testing, and she continued to decline that day. It resulted with her literally crashing. They had to do a rapid response, and it is just like a scene in ER or Grey’s Anatomy. Everyone swarms in and she was bloated and blue, limp. I remember the goal for her blood pressure that night was 30. It was a very long night.”

Millie made it, but her parents refused when her doctors wanted to put her back on a manufactured Ketone diet.

“Once we took her off, everything stabilized, and she is still growing,” Nicole explains.

“We were slowly realizing that our past experiences were equipping us to be confident in pushing for Millie, and what we felt was best.”

In November 2013, the Mattisons saw their doctor in Cincinnati, and an EEG showed that Millie’s brain was seizing 24/7. Her doctor said they could increase her Sabril from 1,000 MG to 2,000 MG, but expectations for relief were low.

The anti-seizure medication Sabril was keeping Mattie totally sedated. They asked that neurologist if medical marijuana would help and were told that it was illegal in Ohio, but they should do whatever needed to help their daughter.

“Our mind was made up,” Nicole says. “We came home; we made our doctor appointments to get a red card [a registration card for the Medical Marijuana Registry]. We booked our flights, flew out here [to Denver] in December, and we moved in January.”

Initially, the couple was wait-listed for Charlotte’s Web, the medical cannabis featured in, “Weed,’’ and named for Charlotte Figi, a child whose parents say the strain reduced her epileptic seizures. Instead, the couple began a regimen of THCA, a raw form of the plant. Neither medicines produce a “high” in users.

In the six weeks Millie has been on THCA, she has had a 75-90 percent reduction of seizures, and just as miraculously, has begun to cry and whine. The first two years of Millie’s life had been totally non-verbal.

“It has been absolutely amazing,” Nicole says. “A normal day in Nashville we would see clusters of seizures, and now, her infantile spasms have disappeared. She is crying a very good deal. We were laughing and smiling and kissing her when we first heard it. We are really excited.”

Friends and family back in Nashville are incredibly supportive of their decision, even if many of them didn’t at first understand. “No one judged or criticized, and everyone was very interested in wanting to know what we knew and what we had learned about this,” she says. “When I steered them to research they would come back saying they couldn’t believe this is illegal.”

The Mattisons say they hope their decision empowers other parents to listen to their gut and do what they can to make the quality of life for their child the best it can be, even if it means moving away from Tennessee.

“I am in contact with seven or eight families across the state and three of them have already committed to moving,” Nicole says. “These are families who are dedicated to the welfare of their children, and I don’t think these are the types of families Tennessee wants to risk losing.”