VOL. 37 | NO. 20 | Friday, May 17, 2013

3-D 'printing' offers new dimension in product visualization

By Joe Morris

Charlie Metz of Novacopy holds a “printed” replica of the Eiffel Tower. Metz is leading the company’s efforts to help area businesses realize the practical applications of 3-D printers.

-- Lyle Graves | Nashville Ledger“Star Trek” characters use a replicating device to whip up instant meals of all varieties. While 3-D printers aren’t yet at that level, advocates say it’s just a matter of time.

For everyone from garage hobbyists and budding inventors to high-end manufacturers of prototypes, 3-D printing represents a huge jump forward in building everything from design prototypes to working machine parts.

Animal limbs are being experimented with, and early steps have been made toward duplicating human parts.

In Middle Tennessee, 3-D printers are being made, leased and sold at price points ranging from a few hundred dollars to well into six figures.

The technology is exciting, but it’s also confusing. Many different types of print manufacturing are being lumped under 3-D printing and scanning, says Melissa Ragsdale, president of 3-D printing solutions for NovaCopy, a company with its headquarters in Nashville.

“The difference between what these printers do and a two-dimensional printer begins with the files they accept,” Ragsdale says. “It must be a three-dimensional file of an object, because the printer then takes that file, reads it and then prints, layer by layer, a physical object.”

‘Additive manufacturing’

The technology has been around for some 25 years or so, but only recently has the convergence of new developments and available equipment allowed for price points that make sense for individuals and businesses.

More evidence of 3-D’s mainstreaming comes by way of the White House, which has created a $200 million, public-private partnership to create three manufacturing centers around the country.

No need to mold clay or piece together cardboard. Product prototypes like this Bosch grinder can now be produced in much more detail using 3-D printers.

-- Lyle Graves | Nashville LedgerEach will emphasize 3-D printing; two will be operated by the Defense Department, while the third will be helmed by the Energy Department. The goal, according to government officials, will be to serve as regional hubs that connect manufacturers and developers with federal agencies, buyers, universities and community colleges.

Sales of 3-D printers have escalated in the last three years, and that’s led to some confusion about what they can and can’t do, Ragsdale says.

“A better term than 3-D printing is ‘additive manufacturing,’” she says. “If a company is making a prototype of something they want to take to market, they used to purchase a block of metal or plastic and cut away with machinery to subtract from that and get their image.

“With these printers, they are layering that plastic or metal together to build the part.”

Additive manufacturing is not without its detractors. A flurry of recent press over 3-D printed handguns has some calling for regulation, and the U.S. Department of State released a directive saying that disseminating files for printing such weapons may violate weapons export rules.

What’s more, legislation has been introduced in Congress that would regulate or even ban the manufacture of guns made via this process.

Proponents, including gun-control advocates in some cases, say that the worry is overblown at this point because it’s still much easier to just buy a gun than it is to fork over the money for a 3-D printer complex enough to make one.

In early May this year, the online blueprint for the first completely 3-D printed handgun, which had been downloaded thousands of times from the web, was removed from the Internet at the request of the federal government.

Printers for inventors, hobbyists

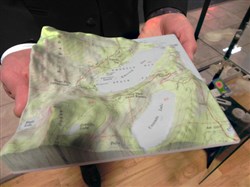

Topographical maps are another application made easier by 3-D printing. This one is on display at Nashville’s NovaCopy, which has played a key role in intoducing the technology to the Midstate.

-- Lyle Graves | Nashville LedgerPrinters use a variety of materials, from thermoplastics to photopolymers to finely powdered metals, titanium and stainless steel. The harder the material, the more complex – and pricey – the machine.

Build-your-own machines range from few hundred dollars to around $8,000, while most small businesses may lay out anywhere from $15,000 to $30,000. High-end printers, those that work in titanium and stainless steel, can cost as $500,000.

“There are a few categories, because the market really has started to divide,” Ragsdale says. “There are consumer machines, which are mostly used by hobbyists and inventors, or who are wanting to provide 3-D printing services. Then there are professional-grade machines, which are being used by industries from aerospace to architecture. Now medical and dental providers are starting to look at them. Then there are the production-grade machines, which are used by manufacturers.”

The low end is where much of the action is, as hobbyists both buy and build machines. Several printer builds have been held at Hacker Consortium, which puts on the Skydogcon tech conference in Nashville.

At around $950 per machine, as many as nine people spent 33 hours building a machine over a weekend, says Trevor Hearn, a.k.a Skydog, who in addition to being Hacker Con’s president also is information security officer at Peabody College at Vanderbilt University.

“The quality of these machines is halfway decent, and it’s a good place to start because you can move up,” Hearn says. “As you move up, the machines become more expensive and so do the materials, so that’s where you see more of the business applications.”

Where he sees the printers being of value, in addition to building prototypes, is in making one-off devices that would cost too much for regular commercial manufacturing.

“I have a friend who does testing for CO2 in lungs, and they had two machines that didn’t have the same mouthpiece,” he says. “They took calipers, designed a part and combined those two to make an adapter piece.

“They can print them one at a time, and use their two machines together. The commercial cost for tooling and manufacturing would have been around $150,000 for that, and now they can make one for about $1,000 each time.”

Professors get in the act

The halls of academe are proving to be fertile grounds for the printers, which nowadays are referred to as rapid prototypers.

“We have three of them just in the mechanical engineering department,” says Thomas Withrow, assistant professor of the Practice of Mechanical Engineering at Vanderbilt.

“They are at different levels because they are used for different purposes. But in general, we use them for prototyping because it’s a fantastic way for all our engineers to learn if they had a good design before we invest a more substantial amount of money into the fabrication of an actual item.”

Walking down the hall at Vanderbilt, Withrow ticks off prototyping projects that either have been done or are in the works by colleagues.

“Michael Goldfarb (H. Fort Flowers Chair in mechanical engineering and professor of mechanical engineering) has used them to make orthotic devices for people with spinal cord injuries because they can be custom manufactured on the additive manufacturing device,” he says.

“We have made prosthetic feet and hands over the past few years, and Robert Webster (assistant professor of mechanical engineering) and Nabil Simaan (associate professor of mechanical engineering) are making a host of other robotic parts and other devices to use in their research and studies. Many of these are prototypes, but others are parts that are built for final use.”

Withrow adds that the advancement of 3-D additive manufacturing is not unlike that of computing itself.

“They started with every expensive mainframes, which had a very large infrastructure,” he explains.

“With manufacturing, you had to send a job to a company. Now you are able to bring it in house where you are, much as computing did with the PC.

“What we have now is much better than what we had a few years ago, and it’s going to continue to improve.”

Health care is major field

Going forward, Hearn predicts that growing hobbyist and small-player interest will keep driving the prices down and the quality up for entry-level, pre-built and build-your-own models.

Nashville Technology Council President and CEO Liza Lowery Massey agrees.

“Just a few months ago, 3-D printing wasn’t really on our radar so much,” Massey says. “Then we held our Techville conference, and NovaCopy was there showing what these machines can do, and now I’m seeing it everywhere.’’

Massey says she sees an increasing number of uses, especially in health care, which makes the technology a natural fit for Nashville.

“Things like artificial limbs aren’t too far away; some people are working in those areas already,” she says. “We have the technology here thanks to vendors, so people can buy it for home or business, and that’s what will get things started.

“What we have to do now is think about the really groundbreaking ways we can use it, not just to reproduce another plastic bottle or keychain, but where we can go in manufacturing, health care and other areas.

“Everyone’s just scratching the surface with this, but with Nashville’s technology, health care and manufacturing sectors, we have many unique opportunities.”