VOL. 37 | NO. 6 | Friday, February 8, 2013

Preserving the Plowboy’s legacy

By Tim Ghianni

The record label chief, real estate tycoon and grandson of one of the most beloved men in country music history leans back in the chair at the end of a maple dining room table, the stout centerpiece of a cramped and haunted room tucked behind a downtown Brentwood insurance agency.

“I think his spirit is definitely here,” says Shannon Pollard, 39, scanning the room that for decades was grandfather Eddy Arnold’s home base for thriving entertainment and land ventures.

He’s not just in this cluttered room to visit a ghost, though. Instead, he’s laying the groundwork for not only reintroducing Eddy Arnold – “some people have forgotten about him, some are too young to know him” – but also guiding the fledgling Plowboy Records, whose name itself is a tribute to the man he loved.

Like his late grandpa, Pollard mixes musical ventures with high-end real estate deals from this building where “The Tennessee Plowboy” came to work almost every day until his 2008 death. Pollard says Arnold’s still hanging around in some fashion. At the very least, he is the business operation’s spiritual essence.

Just as it was during Arnold’s long tenure in this office, the maple dining room table serves as the conference room centerpiece for Plowboy Records.

The room itself is a dusty museum, where not even the mail has been touched in the years since Arnold’s death. Standing out among all the awards and photos that Arnold hung on his walls here is an abundance of yellowed-by-age photos and newspaper clippings of pug dogs, Arnold and wife Sally’s favorite breed.

“My grandparents had a dog they loved, Mr. Nuggles, a pug, in the 1950s,” explains Pollard. “Mr. Nuggles was hit by a car on Granny White (which passes by the Arnold estate). For some reason fans started sending my grandfather pictures.”

Bobby Bare now, ‘Plow-punk’ next

Immersed in his grandfather’s clutter and surrounded by his spirit, Pollard ducks into this room to reenergize while pushing his label’s first product – “Darker Than Light,” legendary country singer and barrier-buster Bobby Bare’s variant take on folks songs, from Tom Dooley to Bob Dylan.

While Plowboy is pushing that album, Pollard and his partners – including CBGB punk-rock legend Cheetah Chrome of The Dead Boys – are immersed in plans for what’s next.

To sonically illustrate that, Pollard plugs his iPhone into his grandfathers’ prized stereo system, filling the room with an eclectic new form of music, something which could be labeled “Plow-punk” – a mixture of Eddy Arnold songs as recorded by the likes of Jason Ringenberg of the Scorchers, Sylvain Sylvain of the New York Dolls and Frank Black of The Pixies – for a late-spring Eddy Arnold tribute record.

While Plowboy Records’ top (and only, so far) artist, Bobby Bare, isn’t on this tribute record, his son (Bobby) Bare Jr. has reserved the right to sing Arnold’s trademark hit, “Make The World Go Away.”

What holds the album together isn’t just the lyrical thread of Arnold’s songbook, but also the session guys: Nashville’s legendary A-Team sidemen, who provided the original Plowboy’s often-lush soundtrack for the more than 85 million records he sold, as well as their younger counterparts, guys like Chris Scruggs and Warner Hodges who relished the studio vibe of statesmen Harold Bradley and Charley McCoy.

And most of the tribute record is being recorded “old-school,” with the singer and band recording together in the studio, explains Pollard as he makes his way around the office.

‘Family junk’ and ‘Cattle Call’

“Except for the snare drums, this is how the office was when he left it,” says the former indie-rock stickman, stepping around a full drum kit and many orphaned bits and pieces from other kits. “You can never have too many snare drums in life.”

Sometimes Pollard just comes here to hang with grandpa’s ghost while banging on the drums all day, or at least as long as it takes to sort the heady swirl of real estate and music deals.

While Eddy Arnold’s museum of clutter is the headquarters and conference room for Plowboy, Pollard’s personal office space is a floor below -- in a room once occupied by Little Roy Wiggins, Arnold’s steel guitarist and sometimes real estate partner.

Every spare space in this building is filled with “60 years of family junk,” perhaps the main reason for not selling this prime space in Nashville’s most affluent suburb to make way for a pet psychologist or a designer tattoo and toe-painting spa.

Most-of-all, it is a comfortable space where Pollard can add his own tasteful clutter while tending to the two primary family businesses of real estate and music.

Like his singing grandpa and Little Roy, his parents – Richard and JoAnn Arnold Pollard – sold real estate from this building. They helped teach that profession to their son. The family patriarch also delighted in mixing real-estate secrets with stories from the road for his attentive grandson.

Fans, and there are mega-millions, know the unforgettable tones of Arnold’s voice. The elder Bare explains it simply: “Listen to ‘Cattle Call’ sometime. No one could touch that.”

The shelves of Eddy Arnold’s Brentwood office remain as they were at the time of his death, complete with photos of pugs and other dogs sent in by fans who knew of the Arnolds’ love of pugs.

-- Photo: Lyle Graves | Nashville LedgerBare, the whiskey-barrel-voiced legend, whose credits include the 1963-Grammy-heralded “Detroit City” and a spot at the head of the table of the so-called “Outlaws” movement, has no reason to hold anyone in awe. His old meat-and-three lunch chum may be the biggest exception.

“’Cattle Call’ is like opera,” he says.

Silent partner’s role in Brentwood

Pollard’s personal office downstairs is nearly adjacent to that of his real estate partner, Steve Armistead, of Armistead, Arnold, Pollard Real Estate Services LLC. The “Arnold” in the name is “our silent partner,” says Pollard, of the gentle giant whose rise to fame began in the 1940s, continued through this century’s “To Life” – a looking-backward-through time’s-telescope celebration and lamentation – and only ended when he died in May 2008, just two months after his beloved wife “Miss Sally.”

A steady stream of mourners passed by Arnold’s casket, opened for viewing in the rotunda of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. The funeral was in the Ryman Auditorium, home of the Grand Ole Opry back when the singer became a member in 1943, five years before Little Jimmy Dickens made that roster, generations before Rascal Flatts.

Of course, recording artists are never really silenced, as long as there are those hungering for the music. Arnold fans have plenty of discs from which to choose, evidenced by the RCA plaque in this “museum to Grandpa” that hails the singer as “the only recording artist in any music genre to mark seven decades on the music charts.”

The Plowboy Records business HQ is located right where it belongs. Arnold is famously known as the man who pretty much “founded” Brentwood – or at least with a few like-minded souls uncovered the potential of the weathered rural patch proudly populated by truck farmers, horse breeders, preachers, domestic workers and the occasional urban refugee. The land reminded the sharecropper’s son of where he grew up in Henderson, about 130 miles west on Highway 100 near Jackson.

Arnold spurred the development of this Williamson County city at Nashville’s southern edge in part to make it an escape for fellow musicians back when polite Belle Meade let it be known the “hillbillies” – who since have turned Nashville into a city unlike any other (and better than the rest, according to The New York Times) – were not welcome.

The piano in Eddy Arnold's Brentwood office.

-- Photo: Lyle Graves | Nashville LedgerStonewall Jackson, Dickens, Skeeter Davis, Marty Robbins, Jim Ed Brown, Johnny Rodriguez, George Jones, Tom T. Hall, Dolly Parton, Carl Smith and Waylon Jennings were (some still are) among those who called the village home. Tex and Tammy lived inside Nashville, but close enough to come here to eat at Nobles and talk music, politics and life with fellow hillbillies … far outside the long shadows cast by Belle Meade noses.

‘Giving Eddy his due’

Arnold’s real estate success is legend. And that’s what Pollard and Armistead are building upon, especially when developing an upscale subdivision on their silent partner’s 61.23-acre estate on Windy Ridge, across Granny White Pike from Richland Country Club.

But it’s the musical legacy the grandson wants to celebrate in the organic development of the new Plowboy label, which he says has as part of its focus “giving Eddy his due.” There’s also a bit of “what would Eddy do” that plays a role in the business and musical decisions.

Plowboy Records’ mission is not to emulate that master stylist and genuine nice guy. The younger man’s musical roots, though seeded by the Countrypolitan crooner, also are flavored by his “almost-at-stardom’s cusp” life as drummer with indie rockers Chilhowie. While the drummer never met radio success, he did meet his most ardent booster, wife, Anissa.

“I met her in the ‘90s when we were playing at The Sutler (a venerable bar and grill that modern times has turned into an empty Melrose storefront). She was there to see the other band. She was in corporate sales with BellSouth Mobility at that time. A grown-up job.

“She gave me her business card, and I called her for a date and we’ve been together ever since.” They have two children, Sophie, 9, and Rowan, 7, who both love to come to their great-grandfather’s office and look at the dog pictures.

The legend’s secretary

Pollard runs his hand along the maple dining room tabletop used by the legend whose mellow, gymnastic tones took tales of love, laughter, cows and mortality to listeners worldwide.

“He would always sit right there,” Pollard says, nodding across the table. “That was where he signed autographs. He always used a silver pen.”

Pollard picks up a long-dried-out silver Sharpie from a stash next to a nameplate proclaiming the head of the table to be the seat of “The Honorable Eddy Arnold.”

“Mrs. Edging would come from her office,” he says, nodding to the cubbyhole – decorated by Marshall stacks – now occupied by Chrome (and his décor of Marshall stacks).

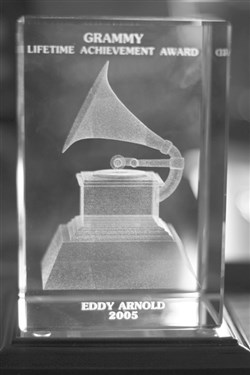

Arnold's Lifetime Achievement Grammy, on a shelf in his office.

“Mrs. Edging would have pictures for my grandfather to autograph, and he always would have her bring them over to this table. He’d get up from his desk and walk over here.” His eyes track the course from the desk, covered with unopened mail – “some of it probably dates back to the 80s” – to the maple table.

“She’d just set the stack of requests down in front of him, and he’d get to work. He signed every one himself.”

Roberta Edging – loved throughout Brentwood long before McMansions with extra cheese killed the pastoral charm – died on New Year’s Day at an assisted living facility. For almost a half-century she came to this office where she made sure the singer’s business affairs were in order. Although she insisted on being called “secretary,” she was much more, an unofficial family member, who stayed to help Pollard after her beloved boss, “Mr. Arnold,” died.

“I really miss Mrs. Edging,” says Pollard. “I get startled sometimes when I come upstairs and I pass what was her desk, where she is supposed to be, and I see Cheetah,” who is many things, from CBGB punk rock icon to Nashville record exec to Crieve Hall family man, but certainly not a charming old woman.

Punk guitarist pays tribute

The former Eugene O’Connor, Chrome was an essential element of New York’s punk scene as a guitarist for The Dead Boys, among other bands.

Some of his punk flavorings can be found on the tribute record, including his take on “What is a Life Without Love.” Harry Potter’s best friend Ron Weasley (actually actor Rupert Grint) portrays him in the upcoming film CBGB about that legendary NYC club’s punk/New Wave heyday.

Chrome says it’s not really a stretch for him to be instrumental – both figuratively and literally – on a tribute record to the kind gentleman with honey-coated voice and instinctive charm.

“I remember Eddy Arnold from when I was a kid and my mother played his records. The first thing that hit me was how great his voice was,” Chrome says.

Then he pauses: “The music was happy, but the lyrics were sad.” That duality – sad tales spun magically to lush music – appeals to the punk rock legend who calls the tribute record “a labor of love.”

“We’ve got a combination of straight-up covers of Eddy Arnold songs and other songs that are not,” says Pollard, as the music plays from grandpa’s sound system.

“I guess Peter Noone (the leader of British Invasion charmers Herman’s Hermits) was the most like my grandfather,” he says of the man who long ago sang about being “Henry the Eighth (I am I am).”

While the voice is “awesome,” it was Noone’s demeanor that most reminded Pollard of Arnold.

“He walked into to the studio and just charmed everybody. He made sure he introduced himself to everybody….made sure they knew he appreciated them.”

Finding singer’s spiritual kin

While “our goal is to reenergize the music of Eddy Arnold,” the company is not planning on continuing to mine the tribute vein.

That’s not to say there won’t be more from this rich catalogue. “We’ll probably work with some more Eddy Arnold songs,” Chrome says.

But it’s not all about saluting the legacy. Plowboy Records’ goal is to focus on the great singer’s spiritual kin, people who perhaps have been passed by time and fashion but whose music is timeless and who are willing to record sans modern gimmickry.

Remember, the first record produced and pressed by this company was not an Arnold compilation but “Darker Than Light,” Bare’s sometimes profane, heart-gripping and lifting collection of folk songs recorded at RCA Studio B, site of some of that singer’s (and Arnold’s) greatest success.

That record was released last November at a broadcast of Music City Roots, an Americana version of the Grand Ole Opry broadcast from the Loveless Barn out in Pasquo.

“It’s doing well,” Pollard says of the Bare project. “You know what’s cool about it is it embodies a philosophy I have that we all share.

“We let that record unfold in the studio the way things used to get done, and basically you get the right band, the right players in the session, the right songs.

“I think what we did was establish something we carried on to the tribute record: Doing it old-school, get the band in and track everything live.”

That, in essence, is The Plowboy Sound, recording live, in the studio, using musicians who played on Arnold’s biggest hits as well as on a constellation of other tracks by folks such as Elvis and Patsy and Johnny and Waylon. There is little room for sonic tricks in the Plowboy world.

“On the tribute record we had several artists come in and play their acoustic and do their vocal live. It’s been real fun to do that,” Pollard says of the almost-completed recording.

“The session musicians we’ve had on there have been real appreciative of how we’ve run things, letting them breathe and do what they do,” at Studio B, the Quonset Hut and the Sound Emporium. He adds that the younger musicians used to help fill in that sound happily embraced the work ethic of the A-Team veterans.

Pollard admits his grandfather may not have liked all of the interpretations, but “I think we’ve been pretty respectful to his legacy…. He was not a rock ‘n’ roll guy, so he may not like some of the rock ’n’ roll interpretations.

“The great thing about his catalogue is that it’s been a joy to work with these songs. A lot of these songs are standards.

“My grandfather had that ability to really pick a song for the quality that he had in his voice. It made it real easy for us to do different arrangements but still have this root of a really great song.”

A spiritual connection

What’s most important to him is capturing the essence as well as the honesty of the man who spent 60 years working out of this humble building in old Brentwood while the vocal-tuned “next-big-thing” was fashioned repeatedly in latex and rhinestones down on Music City Row.

Guitars scattered on both floors of this complex in old Brentwood are testament to another love of the great singer.

“I always thought he was a much better guitar player than he would give himself credit for…He wasn’t the guy who played the guitar later on, because it was a job. If he wasn’t getting paid to play it, he wasn’t playing it,” Pollard says.

“I did the last Christmas, the Christmas before he died. I had my grandmother and grandfather over for breakfast that morning. I picked them up and brought them to my house for breakfast. I laid a couple of guitars around my couch to see if he would pick one up.

“He did. He sat there and played ‘Cattle Call’ for my kids…. So I sat there and played with him and that was a real event to sit there and play with him.”

Pollard finds this office “strange and eerie,” a place where even the squeaking of a door unleashes memories. But it’s also his home.

After turning off the tribute record, he clicks another app on his iPhone.

“How do you do? If you’d just leave your name and number, we’ll get back to you as quickly as we can.” The grandson smiles as his grandfather’s old phone message – taken from the answering machine where Mrs. Edging used to sort through the fan mail – fills the room.

The grandson nods. “His spirit is still here.”