VOL. 36 | NO. 37 | Friday, September 14, 2012

Whiskey Town

By Tim Ghianni

A dead moonshine legend, a former state legislator and a 25-year-old English lit major with a blue highlight punctuating blond hair are key ingredients in a spirited “all for one, one for all” growth industry that’s being mashed, cooked, distilled and bottled in a trio of non-descript Nashville warehouses.

“We’re all in this together,” summarizes Travis Hixon, 39, who daily fills in for the dead moonshiner in the 2,000-square-foot brick space facing the railroad tracks that border Marathon Village’s North Nashville backside.

“A rising tide lifts all boats. We talk all the time with our friends at Corsair and Collier and McKeel,” says Hixon, monitoring the amount of white alcohol trickling from the 1,000-gallon still designed by Cocke County moonshiner Marvin “Popcorn” Sutton before he avoided jail time by swallowing carbon monoxide.

“The bigger the pie, the bigger everybody’s piece,” allows Jamey Grosser, Hixon’s boss at Popcorn Sutton Tennessee White Whiskey, where mason jars are filled with white lightning and dispatched to consumers statewide.

“The people us little guys are competing against are 200-year-old Goliath corporations,” Grosser continues, referring to Tennessee sipping daddies Jack Daniel and George Dickel.

While Hixon and his boss are curators of Popcorn’s time-tested recipe, they proclaim allegiance to the other two “little guys”: valiant comrades in the vanguard of Nashville’s craft distilling industry.

Next week their wares – of varieties white, brown, small-batched, charcoal-mellowed and triple-smoked – will be poured proudly alongside whiskeys from around the country at Nashville’s first-ever whiskey festival.

The three Nashville distillers – Corsair Artisan Distillers, Collier and McKeel Handcrafted Tennessee Whiskey and Popcorn Sutton’s Tennessee White Whiskey – are part of a burgeoning nationwide movement that took its cue from the craft beer boom of the last decade or two.

In that heady movement, mom and pop breweries – in sizes micro, macro and nano – looked at the amber wares and their stout cousins coming from St. Louis, Milwaukee and Denver and decided to make their own particular (and sometimes peculiar) hops and malt concoctions. No, they aren’t driving the big boys out of business, but they don’t have to clean up after herds of Clydesdales either.

Both Hixon – a former craft beer brewer for one of Nashville’s lauded lagers – and his boss point to the success of the small beer producers as a model.

“If we can band together the way the beer guys did early on, tell people there’s another way” to produce whiskey, the craft distilling trade can succeed, says Grosser, who learned how to make white lightning from the bearded, overall-clad moonshiner whose visage is on the label of his product.

“It’s very much a national trend,” says James Verrier, Popcorn Sutton’s vice president of marketing. While there were only a dozen or so such craft distillers a decade ago, there now are hundreds, according to the Distilled Spirits Council of the United States.

“It’s one of the fastest-growing parts of the marketplace,” Verrier continues. “More and more regional players are opening up. It goes back to the whole thing of people going out and making their own chocolate or their own honey.

“It’s not that craft distilling is taking over for craft beer. But it’s very much the same model. And there is more interesting small-batch stuff and distillers are playing around a little. They do seasonal stuff, one-offs, a lot more interesting stuff.”

Collier and McKeel Handcrafted Tennessee Whiskey spokesman Jay Sheridan puts it simply: “The local craft distilling business is going gangbusters.”

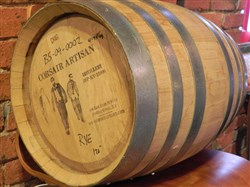

Corsair makes 10-13 different types of whiskeys, all aged in white oak barrels.

In fact, it’s already in the process of expanding beyond the three that all sprouted in Marathon Village. Brothers Charlie and Andy Nelson, 28 and 29 respectively, offer Belle Meade Bourbon, which they buy on a contract basis from a Kentucky distiller. Another Bluegrass State contractor bottles the beverage.

Their goal is to resurrect the Green Brier Distillery business of their “triple-great”-grandpa, Charles Nelson, who distilled and bottled Belle Meade Bourbon as well as “his signature Green Brier Tennessee Whiskey,” Charlie says.

The brothers immersed themselves in family whiskey history a few years ago. Now, after first seeding the venture by offering up the contract product, they’ve signed a lease on a building near what could soon be called “North Nashville’s Whiskey District.” Plans are to begin installing distilling and bottling equipment in November and offer their own products as well as host public tours and tastings by March. Such tours and tastings already are available at Corsair in Marathon Village.

Making it legal

The bustling new distilling trade is taking place in large part due to legislative maneuverings of former State Rep. Mike Williams, now owner, chief distiller and cook and bottle washer at Collier and McKeel.

Before he left Capitol Hill, the Williamson County Democrat helped ignite the craft movement by pushing for new laws regarding distilleries and distilling.

Before the law was adopted in 2009, there were only three counties in Tennessee where liquor could be distilled legally – Coffee, Moore and Lincoln. All are part of the neighborhood where the time-tested “Lincoln County Process” – forcing whiskey through charcoal before aging it (usually in new charred-oak barrels) – birthed Tennessee sipping whiskey’s two main distillers: Lynchburg’s Jack and Tullahoma’s George Dickel.

Under the old law, there were other distilleries by referendum, like Prichard’s Distillery in the Lincoln County community of Kelso.

“We’re kind of the old farts of craft distilling,” says Phil Prichard, who began experimenting with rums in November 1997, gradually making his way to “our double-barreled bourbon” that has been judged among the best in national competition. Since Tennessee whiskey has made a strong comeback, he began producing that storied beverage. “And we make rye and malt that would make any Irishman proud.”

Sweet Lucy, an apricot-orange-bourbon liqueur, is what he calls his “flagship” product. Teal Hollow Springs provides the water that has turned the old Kelso Schoolhouse “into a wonderful little distillery.”

There are other distillers scattered across the state, including the upstart Short Mountain Distillery in Cannon County.

Before the law change, getting a local distillery approved was a windmill-jousting process likely more contentious, even, than the much-ballyhooed Bible Belt ballot battles over liquor by the drink that often pit conservative churchgoers against the forces of economic development.

The new law makes it pretty simple, stating that “manufacturing of intoxicating liquors is allowed in counties that have retail package sales and liquor by the drink sales through voter referendum.”

In other words, unless your county is dry, someone can start making whiskey there – legally.

Of course the legality of making whiskey sort of changed the game for the guy Popcorn Sutton partner Jamey Grosser – a former professional motorcycle racer – calls the “master of craft distillers.”

Sutton, a notoriously successful leader of Cocke County’s famed moonshine industry, actually was the co-founder, with Grosser, of Popcorn Sutton’s Tennessee White Whiskey.

The stills at Marathon Village have launched three brands of Nashville whiskey, Corsair Artisan Distillers, Collier and McKeel Handcrafted Tennessee Whiskey, and Popcorn Sutton’s Tennessee White Whiskey.

“He was a third-generation whiskey maker who had honed his craft to make the ideal drinking whiskey. He told me ‘we don’t f--- around and make sipping whiskey, this is drinking whiskey,’” says Grosser, who was taught that recipe by Sutton not long before the moonshiner chose suicide over jail time.

Sutton – whose story is detailed on the Discovery Network’s Moonshiners – perhaps was the best-known modern illicit whiskey maker. But he certainly wasn’t alone. Filling mason jars with fermented and distilled concoctions is both a time-honored industry and proud family tradition throughout the state.

Any whiskey drinker likely has a source for a jar full and has, at least once, choked it down in an act of tipsy civil disobedience, keeping “the revenuers” from getting their liquor tax dollars.

Marathon connection

The three legal Nashville distilleries and their staffs not only are friends, they all were able to flourish quickly after the law changed by making their products at Marathon Village and under the umbrella of Corsair, which got its permit first.

“Mike (Williams) used our facility for a couple of years,” says Corsair co-owner Andrew Webber. “Popcorn used our facility for a couple of years. Licensing takes so long. We have had benefits by working with them and they were able to produce more quickly because they had a license and were able to get going. We’re all in this together.”

While they share knowledge, equipment and are each other’s cheerleaders, the three produce markedly different products.

Out on 44th Avenue North, where Collier and McKee has relocated after its Marathon beginnings, Williams makes his version of the charcoal-mellowed stuff of Lynchburg and Tullahoma.

The distillery is named for owner Williams’ great-great-great and great-great-great-great-grandfathers, who began making batches of booze in Middle Tennessee a couple hundred years ago. The former legislator’s family owns Collier Farm in Humphreys County, a portion of which is likely where his pioneering forebears fermented their corn crop.

“We make traditional Tennessee sipping whiskey,” says Williams, using a big eye dropper-like mechanism to siphon spirits from a 15-gallon barrel and fill a Glen Cairn glass. “This glass is for nosing spirits,” he says, handing it to the visitor.

“Smell it first and then take a little and roll it around on your tongue. Then you spit it out in the drain,” he says of this sober business practice.

He smiles at the visitor’s expected assessment that what’s aging in white-oak barrels does indeed tastes like the Volunteer State’s trademark spirits.

To achieve what he calls this “totally handmade” result, 1,000 pounds of corn are ground here daily. The result is piped with water into the cooker, producing 1,200 to 1,300 gallons of mash, which travels into cypress mash tubs to ferment for a couple of days.

After fermenting, Williams’ mash goes into the 573-gallon copper pot still. Not all that gets distilled gets used, as “the heart” – the good stuff – is separated from the “bad” heads and tails before completing the journey.

“We make 1.5 barrels a day, if you are judging by 53-gallon barrels,” Williams says. “We use the Lincoln County Process. After it is distilled twice, it is run through sugar-maple charcoal (from Collier Farm timber) seven or eight times.”

Rather than 53-gallon barrels, his distillery uses 15-gallon casks for aging. Each holds 90 bottles of sipping whiskey. One barrel, Williams proudly points out, bears the signature of former Gov. Phil Bredesen, who autographed the empty cask on the day the distillery bill was signed into law.

Williams is nothing if not a slave to his trade. “I probably taste at least 15 barrels a day,” he says, adding that each bottle sent out the door bears his fresh-ink thumbprint on the stopper.

An unaged white whiskey product also is produced here. And in the same building, SPEAKeasy Spirits, a separate company, uses Williams’ aged product as primary ingredient in Whisper Creek Tennessee Sipping Cream, a soon-to-be-marketed liqueur that may do for Lincoln County Process liquor what Bailey’s Irish Cream did for the Emerald Isle’s malt hooch.

“This is a labor of love,” says Collier and McKeel’s Williams, slowly sniffing some product. “We want to make the best Tennessee whiskey you can make using traditional methods.”

‘The Adventurous Distiller’

It’s not Tennessee tradition that’s on the agenda of chief distiller Andrea Clodfelter, the blonde with the colorful streaks at the Corsair Artisan facility that fronts the 12th Avenue North end of Marathon Village.

Libation experimentation is the key for Clodfelter, who does everything from milling to distilling to bottle-filling.

Raising her rubber boots to move about the cramped distillery, the former UT-Chattanooga English lit scholar points to sacks filled with varieties of grains cooked up for consumption in the primary, 250-gallon copper still.

“If it has starch in it, we’ve tried it,” says the young woman who now is experimenting with quinoa, a seed that’s related to spinach and beets.

One of her bosses, Darek Bell, has even published a book on the topic. “Alt Whiskeys: Alternative Whiskeys and Techniques for The Adventurous Distiller” – available at the distillery – lists just some of the grains Clodfelter has used in experiments in this facility where the “alt” – infusing whiskey traditions with punk-rock mystique – is as pungent as the malt.

While Collier and McKeel’s Williams sticks to the tradition of corn, rye and malted barley, Clodfelter’s ingredients are various. In addition to quinoa, her “alt-grains” list includes (but is not restricted to) amaranth, oats, spelt, kamut, triticale, milo, teff, millet, fonio, Job’s tears, wild rice, emmer, black rice, blue maize, einkorn and tritordeum.

“There have been 37 different types of whiskeys made here, but right now, we’re making about 10-13 types,” she says, smile glistening as today’s grain compound is piped through the wash and mash process and into the American white oak aging barrels.

Eventually the whiskey du jour ends up in the decidedly non-traditional-looking bottles Bell, 38, and co-owner Webber, 37, have chosen for their wares.

The modern-looking bottles and graphics purposely set their spirits apart from the white-lightning mason jars and square-edged whiskey bottles.

“Mike (Williams) makes a Tennessee whiskey, Popcorn makes a moonshine and we make oddball whiskey,” says Webber, of the company formed 5½ years ago. “We don’t have a ‘Grandpappy was a moonshiner,’ story.”

Indeed, their story actually begins when the two partners tired of a biodiesel project that used tanks of frying grease to make fuel “for school buses, as well as for Darek’s diesel fleet at Bell Construction.”

“One day I had enough. … I collapsed and said that if that tank was filled with whiskey rather than fried grease, I’d be a happier man,” says Webber of Corsair’s light-bulb moment.

The two high-spirited buddies “spent a year working on the business plan, learning anything we could about the industry as well as home brewing and home winemaking.”

Once they had a viable and smooth-tasting plan, they filled out appropriate paperwork and began production in Bowling Green, Ky.

“That was before the craft whiskey industry really boomed” and when Tennessee’s old distilleries laws existed, Webber says.

When the law changed, the men moved their brown whiskey-making operation into the old Yazoo Brewery site at Marathon (the brewery had outgrown its locale and moved downtown to Division Street.)

Since that day, Corsair has prototyped and produced whiskeys in Nashville while using the Bowling Green facility for unaged, white spirits.

“We are not what you would expect to find in a Tennessee distillery,” Webber says. “We like to play with smokes (like their Scots whiskey-like triple-smoked barley), alternate grains and unusual preparations.

“We have a whiskey called Rasputin that is a Russian imperial stout-style beer that we distill and pass through hops. We use grains that no one else has used” and are not afraid to mix-and-match, leading to things like their award-winning nine-grain and 12-grain bourbons.

Using the different woods to smoke their diverse grains is another element. “We’ve fooled around with everything from apple to nectarine. Think of a wood that is ideal for a cookout and we’ve tried it.

“A lot of the small craft distillers are still trying to make a traditional bourbon … we’re trying to push the boundaries of what can be done.”

Those boundary-pushing products can be found on shelves in 25 states.

Just around the corner of the Marathon building, scant yards from the Corsair distillery, Hixon and his Popcorn people are filling eight mason jars a minute, hand-tightening 500 tops an hour, in their race with demand.

As Hixon mops his brow, he smiles. “I think there’s a lot of growth to be had in the craft distilling industry.”