VOL. 36 | NO. 26 | Friday, June 29, 2012

Middle Tennessee inventors find the path to a patent is shortened with guidance from experienced attorney

By Joe Morris

Daniel Cooper’s Cooperstand was invented after the guitarist found himself in need of a guitar stand that could fit inside a guitar case.

Guitarists wrangling equipment in the rain owe Daniel Cooper a debt of thanks. The same goes for trucking companies who know where their trailers are, compliments of Trackpoint Systems.

These two Middle Tennessee inventors have been able to get a bright idea to market via the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. They were helped along by attorneys from Stites & Harbison, which maintains a Nashville office and has been listed as one of the top trademark firms in the United States by Intellectual Property Today magazine.

Having this kind of patenting know-how available was certainly helpful to Cooper, who along with partner Melanie Dyer own Cooperstand, a company selling his invention, a guitar stand that folds up for storage within a guitar case. As Cooper tells the story, it was a dark and stormy night …

“We were playing at Douglas Corner, and there’s no overhang to their door; it’s right on the sidewalk,” he says. “It was pouring rain, and I had a guitar stand in one hand, a guitar in the other and couldn’t open the door.

“‘Someone needs to invent a guitar stand that fits in the case,’ I said to myself, and so I started working on it that night.”

David Nagle Jr., co-chair for Stites & Harbison’s Intellectual Property & Technology Service Group

Two dozen prototypes later, there was a workable stand. Dyer was focused on protecting the product, and so she and Cooper met with attorneys and quickly set about getting a provisional patent. They then worked the floor at the NAMM show, a huge music-industry convention that brings together musicians and manufacturers, and quickly got their new stand into mass production.

That was in 2009, and about two years later the full patent was awarded. That’s much faster than the usual four- to five-year wait, and the turnaround was largely due to research and collaboration between the lawyers the patent office, which turned up no competing or similar products.

The quick patent has also led to two related efforts for stands that are now in the works. About 30,000 of the original stands have been sold to date, making a strong return on the investment, Cooper says.

“The patent process is not cheap, and can run you as much as $10,000 to get it going,” he points out. “It depends on how many times you have to respond to inquiries from the patent office.

“The attorneys were very helpful because they have a music base here in Nashville, and so were very empathetic, but also keep things moving throughout the process so that you can get to market while it’s pending, but also finalize everything as quickly as possible.”

Momentum is key. Inventors often get stalled due to the complexity of the patent process and give up, or wind up selling their idea to someone who can take the longer view, notes David Nagle Jr., co-chair for Stites & Harbison’s Intellectual Property & Technology Service Group.

“We make sure that the client has some form of legal protection right away, and that can take different forms,” Nagle says. “We negotiate that with the patent office so that we can build a fence around the intellectual property so the inventor can begin his or her new venture.”

Patent attorneys are members of the state bar who also must sit for an exam given by the patent office. To qualify, a science or engineering background is required.

“We have to take information from technical people and translate that to legal documents,” Nagle says. “You’ve really got to speak their language.”

The firm has two types of clients: the garage inventor, who literally has come up with something in a home workshop and wants to get it to market, and larger entities such as Vanderbilt University, which spin out intellectual property generated on campus.

Nashville’s health care community also provides plenty of work, whether it’s patented products or trademark and copyright issues, Nagle says.

“Whatever we do, it always starts with a patent search: Does something like this already exist? We have to identify what makes this product different, and what the competitive advantage is. If it’s unique enough, and there’s nothing out there that’s near it, then we can prepare a patent application,” he explains.

The application is a two-pronged affair, consisting of legal and technical descriptions of the invention. That information includes what it is, how it works, who benefits from it and all uses.

Ben Schnitz developed and patented the TrackPoint System for tracking and monitoring trucks.

Then the patent office performs its own research, and eventually comes to a decision regarding the issuance of a patent.

Most cases are usually rejected, and those that do make it through take several years, Nagle says, adding Cooper’s initial patent was extraordinarily fast.

“Most cases are usually rejected, and then it becomes almost a negotiation process,” he says. “It’s really about the scope. Often you can get a patent approved, but it’s for a really limited scope of use.

“We work to get the broadest coverage possible, and in the meantime tell the client to go to market with a patent-pending position because just having that will have a deterrent effect for anyone trying to copy them.”

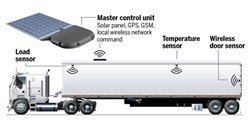

The longer process was what Ben Schnitz, CTO of TrackPoint Systems, experienced with his GPS tracking system for truck trailers.

He and his co-founders were working for another firm in 2003 when they developed the technology and, when that company went out of business, they pursued the application on their own. That led to TrackPoint, and eventually an industrial client base.

“Nashville is a real hotbed for trucking activity, and we thought our technology was a logical fit for that market,” Schnitz explains. “We then look for investors, and one of the first question they always as is, ‘Is your product patented?’ We wanted to be able to say there was a patent pending, so we began working through the process to make that happen.”

The entire process took about five years, and the patent was awarded in 2011.

Having a full-service patent attorney nearby was key to the process, Schnitz says, because it allows for ongoing dialogue as questions come back from the patent office. It also has led for some out-of-state business for all parties.

“Now we are working with Florida Power & Light on a tracking device for mobile fuel tankers,” he says. “Once we began to develop it, we decided to pursue a patent. Florida Power & Light was pushing for their attorneys to do it, but Stites won them over with their capacity for full-service work.”

Patenting isn’t for everyone, but it does have its rewards. It can also be mildly addictive, Cooper notes.

“Once you do it, you might want to do it again,” he says. “I’m 65 years old, and many times in life I let opportunities go by.

“Now I have people who are willing to look at drawings, even tweak them, and put together something the patent office will understand. It’s not easy, but it can be cost effective when it’s done right, and it can get your idea to the marketplace and make you some money.”