VOL. 44 | NO. 12 | Friday, March 20, 2020

Feeding tornado victims while avoiding the new killer

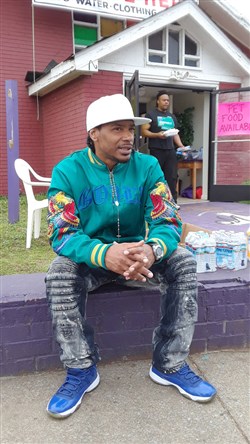

King Antonio takes a breather from his continuous volunteer work loading groceries and supplies into cars and doing whatever else he’s needed to do in the disaster-relief effort offered by The Church at Mt. Carmel. A photographer, videographer, entertainer and more, “a jack of all trades,” King Antonio, who grew up going to this church, admits the coronavirus emergency is frightening when he’s dealing with so many people, but he’s not going to stop offering hugs to those who need them.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni | The LedgerKing Antonio – resting briefly on a 2-foot-tall retaining wall in front of his battered “home church” on Monroe Street – admits he’s worried about coronavirus, but he knows his time is better spent helping his old neighborhood dig out of the more-tangible disaster, the rubble left by the tornado.

“Who’s not worried?” he asks, when talking about the pandemic. “All I can do is wash my hands. And hope.”

Since the March 3 tornado brought him to The Church at Mt. Carmel to distribute smiles and necessities to powerless survivors, he has pondered this viral national emergency. But not for long.

King Antonio knows the tornado refugees need help, and he declines to let coronavirus fears slow him from delivering. “I wouldn’t call it being naïve. I take the precautions I can,” he says. “If it’s supposed to happen to me, I guess it will.

“There’s nothing we’re going to be able to do about it. It’s like in the Bible. The message is: ‘We need to get it together as a people.’”

He nods at one of hundreds of people who stream daylong to this church in a horrifically defaced section of North Nashville. They need help. Hell, they need almost anything, because they have lost so much.

When asked to explain the regal name he has adopted, King Antonio smiles.

“My middle name is Leon, which means ‘Lion-like,’ like ‘The King of the Jungle’ and I serve ‘The King of Kings,’” he says, before pushing himself to his feet to help load a car for one of the tornado-stricken. Dog food, toilet paper, baby wipes … and while he’s at it, he throws in a case of water.

Basically, The Church at Mt. Carmel, in the neighborhood where my regal new friend grew up, has been turned into a “c’mon in and get what you need” sort of superstore, where congregants – likely in want of physical and emotional rescue themselves – toil to make sure all who enter get what they need.

“I live up off Trinity Lane now, but I still come here,” King Antonio says, nodding back toward the damaged brick church that has become the hub of help for many: Mostly black, but some white … whoever makes it past police barricades, downed utility poles and assorted tornado carnage to arrive at 1032 Monroe Street.

Since the March 3 disaster, folks have been coming nonstop in pursuit of supplies and spiritual uplift. During my visits, a few have told me the coronavirus pandemic worries them, but right now they need to feed their grandmothers, babies, puppies and kittens and recover from the brutal storm, its carnage needing immediate attention.

The coronavirus is a furtive and underhanded attacker, a sirenless and silent assassin for which none of us, from the bears of Wall Street to the president of the United States of America, were prepared.

The tornado has changed the neighborhood’s face, its physical – though not spiritual – character. Blue tarps cover roofless homes. Whole blocks are punctuated by crumbled brick, downed utility poles – many snapped in two -- and uprooted trees.

The vacant lot next to the church overflows with this refuse, some pulled from the church. Other stuff – plywood, insulation, glass shards, twisted siding, etc. – has come from the house behind the church, that lost its entire upstairs, blown right off, and from other neighborhood cleanup.

I’d been in this neighborhood – at least as far as the cops would let me – and in Germantown and East Nashville and at the Red Cross Shelter at Centennial Sportsplex hours after the storm whipped through, literally breaking Music City’s heart.

Or at least severely injuring it.

And I’ve spent more days out here, scouting for hope while talking to still-shocked folks, all the while marveling at general good cheer and resignation.

It’s at this church where I discover the sought-for hope. And one of its most-ardent providers is King Antonio – a gospel artist, studio owner, photographer, videographer who calls himself “a jack of all trades.”

“I’m going to be out here until everything is done,” says this sorta-kingpin of a loosely formed church task force that toils 8-8 daily. “I have jobs where my schedule is flexible, because sometimes I’m on the road entertaining. So I’m going to be here until everything is up and going.”

In addition to canned goods, Gatorade and fresh meat from the church freezer, these neighbors in need also are encouraged to eat or take home the barbecued chicken, prepared constantly by congregation members.

Finally, about 10 days after the deadly storm, food-prep relief arrives in the form of a Crisis Response International kitchen on wheels that for a week and a half had been parked on Holly Street in East Nashville. Their menu is barbecue, chicken and baked beans. There is speculation about a pot of chili in the evening.

Rubble from tornado damage to the church and the neighborhood fills the landscape next to The Church at Mt. Carmel, to the rear of the picture. Despite damage to the church building, Bishop Marcus Campbell and his congregation are focusing on helping folks who are in need after the March 3 disaster.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The LedgerStanding in front of the house next door to the church, Belinda Campbell – “this was my mom’s house,” she says of the home where she was raised and where she raised her own children – says inspectors told her the tornado did some structural damage to her home, but she’s OK and can stay there pending repairs.

Belinda gazes across the street at the large, two-story, basically new houses that replaced the old neighborhood dwellings, sending her friends and relatives as far away as Clarksville (or Trinity Lane.)

“The gentrifieds are here,” she says, adding that as far as she is concerned “that’s not a good thing.” Of course, the houses built after the neighborhood cottages were scraped away haven’t escaped damage either, and this church stands eager to help these mostly paler urban settlers.

Tornados know neither race nor social class.

“I was layin’ on the couch, and all of the sudden everything went ‘Woomph’ and the sirens went off,” Belinda says. “I came out. Down there one lady’s child was pinned up beneath all of that rubbish,” she notes, nodding down Monroe Street and adding the child made it out OK.

While she waits for a brother to bring a KFC box-lunch back to the home where they grew up, she directs me to “my son, Bishop Campbell. He’s better at talking than me. I like to stay in the background.”

Bishop Marcus A. Campbell, who grew up in Belinda’s gray house, strolls from his church – where he’s pastored 14 years – to try to talk his mother into telling me about the neighborhood and the storm damage.

“He’s the talker,” she says, nodding to the pastor of the church whose front door is 20 steps from the family home.

“I got christened as a baby in this church,” says the former tractor-trailer driver who was selected by the congregants to lead this church. “I have services here at 9:30 Sunday, then I go to the other church I pastor, Second Missionary Baptist in Ashland City. I get done here and then go out the front door to get up there. It takes 25 minutes. Service there begins at 11:30.”

His “bishop” title comes from his position as top state officer of the Leaders for Change Christian Fellowship, an organization of preachers and churches whose goal is “to produce an atmosphere of positive change.” The 20 churches in the fellowship in Tennessee and those in other states currently are all black, he says, adding he’s working on changing that: “We need to get some white churches, some Hispanic churches in the fellowship.”

Bishop Marcus A. Campbell oversees the distribution of food, water, diapers and other supplies needed. His sanctuary has been turned into a free groceries and love dispensary for folks in the tornado-ravaged stretch of the city near The Church at Mt. Carmel as well as for those from anywhere who suffered from the March 3 tornado. Since he is always around groups of people, he is mindful to take precautions to keep coronavirus at bay so he can fulfill his mission.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The LedgerHe and his family live in East Nashville’s Sam Levy Homes, and he is on the MDHA board of commissioners as well as active in the fight to stifle Music City’s gang problem by promoting pride, peace and prayer over pistols.

Today, though, and for days to come, he’s focusing on healing his neighborhood as well as the church, a damaged mecca of hope for tornado victims.

“We’ve got roof damages, gutter damages, it broke down the fence, the glass on our shuttle buses broke, the ceiling in the pastor’s study caved in, ceiling in fellowship hall caved in and the ceiling also was damaged in the men’s and women’s bathrooms …”

Those repairs will come later, perhaps in another week or so, after all those needing help have gotten what they need inside the sanctuary where the padded chairs were pushed back to make room for tables of life-giving supplies.

The preacher’s big voice is drowned out by a guy in a Red Cross truck, using one of those “Blues Brothers” loudspeaker setups to offer up “hot chicken and dumplings” to all comers.

I can’t tell – there are so many cars jamming this street, seeking help from Marcus’ church – if anyone goes for the offer. But there’s so much desolation within these few, tight blocks, that I’m sure the dumpling man found some takers.

The bishop tells me that in addition to the church’s resources, a cluster of his friends, pastors from several black churches in Stanton, west of Jackson, have brought a truckload of supplies.

“We brought a care package,” says Pastor Robert Whitley of Good Hope Baptist Church, one of that group of preachers, who steps away from his brethren for a moment.

They’ve unloaded, and it’s time to get back on the road – “It’s 200 miles,” Pastor Robert says.

“We brought toiletries, hygiene products for women, hygiene products for men, clothes, food,” he adds.

“You’re supposed to help your neighbors out,” says this spokesman for the Stanton churches, eyes trailing to the open church doorway, where a continuous flow of people go in empty-handed and come out with a cart – or perhaps King Antonio’s arms – loaded with essentials.

Bishop Marcus A. Campbell, sitting for a moment, gets a helping hand from Javon Lynn, one of seven children he shares with wife Stacy Campbell. Javon is ready to roll the hand-cart into the church to load up anything from dog food to diapers to help people who come to The Church at Mt. Carmel for necessary supplies because of the tornado.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The Ledger“These,” Pastor Robert says while watching the goings-on, “are our neighbors.”

Bishop Campbell, the child they called “Marcus” when he grew up in the house next door, welcomes all the donations.

“Thousands of people have come here since we been doing this since the Tuesday of the tornado,” he points out. “A massive group of folks, they been asking for a lot of diapers, baby wipes, toilet paper, cat food, dog food, disinfectant wipes, pillows and blankets. Food, too.”

Since there’s not yet been power restored to the whole neighborhood, folks come here seeking to replace food that spoiled in their refrigerators. “I been going out and buying some fresh meat,’’ he continues. “I just looked in the church freezer, and it’s all gone. Need to go get more meat today.”

The church will need attention and repairs, but that is put on the backburner while this proud little congregation – most of whom have been forced out of the neighborhood by It City development – focuses energies on helping all-comers.

“We ain’t going to stop as long as we can help people,” Marcus says. “I’d rather that the church be able to stand, but you can’t always get what you want: You get what you need.

“I can feel it. I think it is going to be OK. … It’s great to see everybody out here, coming together.”

A honking white car noses toward the curb, and Marcus goes over to talk with the driver.

“Look at that,” he says, when he returns. “That man is driving his father, a World War II veteran who is 99. They haven’t had power for a week, so all their groceries went bad in the refrigerator.

“I gave him $100,” he says. “They (the preachers from West Tennessee) gave me $200 and told me to give it to people who need it. I’ve still got another $100 to give away.”

His hope, of course, is that after people get back on their proverbial feet, they’ll remember this kindness and pay it forward.

“I’m runnin’ on fumes,” Bishop Marcus acknowledges. “We’ll meet the need from the storm as long as we can, and we’re always here to help the community.”

He, too, is a bit troubled by the invisible threat of the coronavirus that adds another level of worry to those trying to do their best to survive in the rubble.

“Lately, I’ve had some concerns about it,” he says. “All we can do is wish for the best as we pray that God has got his hands on us.”

There have been hordes of people here, and he and his crew of neighborhood saviors have touched or been touched, both in the heart and physically, by most of them.

Add to that the close contact in the sanctuary and when loading the cars.

“We’re just washing our hands and sanitizing,” he says. “Been doing a lot of that.”

Marcus admits “when you want to be more embracing to a person, it (the virus) makes you hesitate.” In many hours there, I didn’t see him pull away from a single handshake or hug, despite the congestive heart failure that has him on disability at just 46.

King Antonio just has loaded another cart of goods into the backseat of a car. He teases the two small children who are “helping” their mom with this chore. I notice a large bag of dog food among the stuff he loads up.

“People got dogs and cats. They got animals that were affected by the tornado,” he says, obviously happy four-legged friends have not been forgotten.

He stops to think again about the day of the tornado and what he thought when he heard his home church, the neighborhood – where, as a youth he partook in “adolescent behavior, some of it not so good” – had been coldcocked.

“I got a heart for the people,” he says. “When I seen that the tornado hit, I was out of my mind: I was seeing all of these things, the damage.

“I’m ‘Now what? I gotta do somethin.’ I know I gotta do somethin’ to help.’”

At 39, he has “strong arms, strong legs” ready to lift and load, help however needed.

There are needs he sees but can’t fix. “These people need help, financial help. Most are living paycheck-to-paycheck, day-to-day. If you see someone in need, help them.”

As for the coronavirus and his worries while among these folks: He has adopted the fist-bump rather than the handshake, unless, by reflex, he forgets. He washes his hands. Sanitizes. And prays.

“Lovin’ on people be the main thing,” he says. “Be nice to people. Hug on people so they don’t feel like they are out there by themselves.”

Yes, those hugs can be risky propositions these days, and while he knows that, he also knows his hugs are needed.

“My calling is to help people, empower people,” he adds.

“Make sure my soul is right, my spirit is right, make sure when I come to God for my one-on-one, I’m ready, I did what I was supposed to do.

“I didn’t burn fires, I light lights.”

We shake hands, and he goes back into the crowd of people in need. A fist bump quickly turns to a hug.