VOL. 43 | NO. 48 | Friday, November 29, 2019

Guthrie honors man who did ‘so much good’ for others

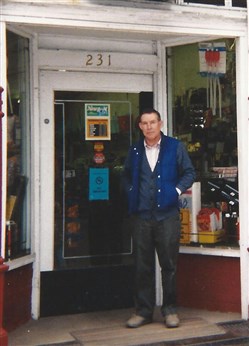

The late Bill Longhurst, known as “Mr. Guthrie” for his leadership and love of his hometown, Guthrie, Kentucky, outside the Longhurst General Store on Ewing Street.

-- Photograph ProvidedRed-tailed hawks soar over the town tucked along Ewing Street in the Southern Kentucky farmland where the James Gang (with Jesse, not Joe Walsh) visited, where Robert Penn Warren was raised, tossing rocks and having fun with future major league pitcher Kent Greenfield, and where Bill Longhurst spent his life casting a giant shadow of wisdom, hometown pride and love.

Now that gentle and kind man, his image cast in bronze, forever will be sitting on a bench, looking toward Ewing Street (U.S. 41) from Longhurst Park – across from Bill’s now-silent general store – where Saturday a statue of a man I proudly proclaimed for decades a trusted friend will be unveiled.

Bill, who died in 2018, was the first person I’d stop to see whenever I visited Guthrie, Kentucky, going back into the 1970s. He’d always be at the counter of Longhurst General Store, visiting with the hangers-out and hangers-on, talking about Guthrie politics and historic pride – from tobacco wars to outlaws – unless he was standing just outside the storefront, literally watching the wheels go by, as there is no such thing as a traffic jam in this wonderful city.

If he wasn’t in his store, well, chances are he was across the street at Boogie Oliver’s Guthrie Hardware, sitting down with friends, including Boogie, of course.

“Bill was the most important person we had in Guthrie,” says Boogie, whose real name is Henry but who for his life has been known only by the nickname given him by his teenage sisters because as a toddler he danced in his crib to the rock ‘n’ roll music they played. He “boogied.”

“He came over here (to Boogie’s store) when things were quiet at Longhurst’s,” says the hardware store owner. “He’d pull his chair around, so he could see his front door, so he could see what was going on in his store.”

Basically, all Bill was doing was keeping track to see if anyone was going into the family general store, seeking goods or other stuff from the establishment that had a sign indoors reading: “If We Ain’t Got It, You Don’t Need It.”

Bill’s dad, William Sr., always “Mr. Longhurst” to me, pointed that sign out on my initial visit all those years ago. It was a genuine promise of the stock-in-trade.

From his perch at Boogie’s place, if Bill saw someone step up into the store he kept open mainly because of his love for his town, he’d smile quickly and eagerly stride across Ewing to the general store his father opened for business in 1937.

The elder Longhurst – also a friend to this writer when escaping the storms of life – eventually talked his schoolteacher son into joining the enterprise full-time. The senior William – who fixed my first sandwich of the Rev. Reuben Toliver’s barbecue – has been gone a long time.

His son kept the store going even in Guthrie’s long and melancholy fade, when it became more likely people would drive down U.S. 79 to Clarksville’s Governor’s Square Mall and its surrounding anonymous storefronts than stop into a weathered, old general store.

Longhurst General Store closed March 23, 2018, the day Bill Longhurst died. The “closed” sign he placed on the door before going home that night has not been touched.

“He had been watching a basketball game,” says Mack Linebaugh, Bill’s lifelong friend who made a name for himself in the Nashville banking world – including a long stint at First American and then as president of Bank of Nashville – before moving back home. Mack always planned on retiring to his 350 acres, where he raises soybeans, corn and wheat – “no livestock” – on land farmed by his family since 1852.

“It was the NCAA tourney,” he says when I catch him changing the battery on a tractor on the land on Fairgrounds Road, just inside the Tennessee state line in Montgomery County.

“Guthrie is our nearest town,” says Mack, who grew up as Bill’s best pal.

“You know Bill was a big Kentucky fan. Unfortunately, Kentucky lost that night. He got up to go to bed. There was a loud sound, and the dog barked. Elaine found him. He was 79.”

“I found him on the kitchen floor,” says Elaine, who assumes it was a heart attack that killed her husband, who was known for his robust physical health, his quarterly doctor’s checkups and his advice to me on how to age gracefully rather than succumb to the already-visible ravages: “Just keep on moving, Tim. Keep on moving.”

“It was a shock,” Elaine remembers. “He wasn’t in the hospital. He wasn’t in the nursing home. It surprised the people of Guthrie at least as much as it did me. He wasn’t sick and came home to watch a Kentucky ballgame, and, of course, they lost.”

Boogie sadly recalls the final encounter with everybody’s friend: “Every afternoon before we closed up, I went over there, or he came over here, right before closing time. I went over there to his store that day. We were talking Kentucky basketball. I left about 4 or 5 and told him I was going to come back over (to the hardware store) and lock up and leave.

“His son (Russ) called me about 3 a.m. and told me Bill had died. I stayed at their house until they took him out.

“Nobody that I’ve ever known lived any healthier than Bill did … Bill’s daddy lived to be 95. Bill told us he was going to make it to 100. I guess we all believed him. It was a blow to all of us and to all the city of Guthrie.”

The store never reopened. At least not yet.

“It’s kind of sad, really,” says Elaine, who is on the board of the Robert Penn Warren Birthplace over at Third and Cherry, a fine museum displaying the roots of that great American writer.

I long ago befriended Robert Penn’s brother Thomas, who operated Warren Elevator at the edge of downtown. Thomas, to whom I was introduced by Mr. Longhurst on a cold day inside the general store, took me to the now-vanished grain elevator, where he told me: “I love my brother, but I don’t understand what he’s writing about.”

Thomas and other members of the family clipped out my writings about Guthrie and sent them to Robert Penn, who passed back word that he was a fan. I’m proud to have some of that writing in the birthplace museum. He was planning a return to his beloved Guthrie to see the new museum when he died Sept. 15, 1989.

As for Longhurst General Store in the days after Bill died: “We cleaned it out pretty much,” Elaine tells me of the store that “caught last light before it was shuttered,” as the great poet wrote in his “What Voice at Moth-Hour,” an apparent reminiscence of adolescence, sights, sounds and voices in this kind agrarian village.

“All the stock is gone,” says Elaine, who easily matches her late husband’s kindness and love for Guthrie.

“My dad’s passing was unexpected,” says Russ Longhurst, a professor of engineering and physics at Austin Peay State University in nearby Clarksville. “It’s taken us some time to take the next step for the building.

“A lot of people in the community ask me if I am going to open the store and carry on the family tradition,” he says. “That’s not in the cards at this point in time. I have a career.

“I never rule out anything,” the 46-year-old adds.

Someday another older Longhurst might be peddling Amish and Mennonite goods, barbecue and the thick bologna sandwiches that Bill not only sold but gave away to anyone who was hungry. He also made sure no one went hungry at Christmas. He had the food in stock. He shared it quietly, unheralded, beloved, unsung by choice.

Unknown to almost everybody, including his son, was the fact he conspired incognito with a friend to ensure those in need had meat on their tables all year long.

“I remember when I was working in the store (as a youngster), Dad would give me a slice of bologna to take out to a stray dog back in the alley,” Russ says.

“Bill was always an extremely likable guy,” recalls his lifelong friend Mack Linebaugh, who is “81, like Bill would be.”

“He was quiet in his own way, but yet competitive. He loved to play golf. Basketball was his big sport. And he coached basketball and baseball.”

Some of that baseball was played decades ago at Kent Greenfield Park, a ballfield Bill helped construct behind his family store. The Little League Park was named for the former major league pitcher, Robert Penn’s best friend, who took the mound for the New York Giants and Brooklyn Robins, as the now-Dodgers were known 1914-1931.

Both boyhood adventures and the pitcher’s brown-liquor-fueled fall from glory are among the poet’s topics. I got to know Mr. Greenfield as a sober and kind man who raised prize-winning bird dogs in Guthrie.

That ballfield is long gone – Little Leaguers, including Bill’s own sons – went to play down in St. Bethlehem, part of Clarksville, instead.

But the store building’s still there, and the family plans to revive it in some fashion.

Russ won’t be manning the counter for a long time, if ever. For now, though, he would like the building to reopen as a general store, and there have been suitors, which pleases both Russ and his mother.

“My dad, what he shared with me many years back, is he wanted the store to remain a part of the community after he was gone,” Russ adds. “We’ll keep our options open, but most likely what will happen is we’ll lease the building out to someone so they can open a store.”

Mom Elaine is all for seeing the store become what it was again, a place for people to shop, get their bread and canned beans, maybe some barbecue, gentle companionship, bologna and an icy Coca-Cola.

“We’re trying to get it fixed up. We put a new roof on it. Looking at it, it does need some more work done on it. We’ve got several projects we need to do,” she says. “I hate to see an empty building in the downtown district.”

There long have been empty buildings downtown, but Bill’s was the place where a guy in need of advice, comfort or doses of tobacco-war and railroad history would find his daily smile.

I’d frequently go there, seeking to destress from the newspaper world, which consumed my waking hours. Nightmares, too, as those 14-hour days of teenage bodies, tragic wreck scenes, Fort Campbell soldiers killed and the like haunted my sleep. And fueled nasty habits beyond taking tea at 3, of course. So, I’d seek solace.

“I think I’ll go see Bill,” I’d say, whether I was working in Clarksville, a half-hour down what eventually became Wilma Rudolph Boulevard, or in Nashville, from which I’d generally take U.S. 41, passing the Carnal Garage (truly the name of a long-gone business whose name I cherish. I wish I had a T-shirt.), and even past the old Kimbrough Hardware building where the owner’s blood drained out onto the front steps after a robbery long ago.

It was in my column about how those dark stains on the hardware store’s front stoop brought stark modern reality to Guthrie that I first compared this usually peaceful town to Andy Griffith’s Mayberry. I went to Longhurst General Store after visiting the stoop where Charles Kimbrough bled out, where I touched the stains of that in the darkness at the edge of town.

Bill and I talked of the tragedy just on the other side of the railroad tracks (Guthrie once was a regional railroad hub and before that a main stop for stagecoaches). Until they tore it down in the last couple of decades, the steam-locomotive coal tower still straddled the tracks a mile or two south of town.

While in the store that deadly day, I’m sure I did as always. I got some Reuben Toliver whole-hog barbecue – prepared over the Rev. Reuben’s pits down in Sadlersville – and some baked goods from Schlabach’s Amish Bakery out on Guthrie Road to take back to The Leaf-Chronicle newsroom, where I was associate editor and columnist and in charge of the Sunday newspaper. Gotta fuel the troops. Sometimes, if I had time, I’d drive the short distance out into the corn and tobacco country to that bakery.

Then I went to the Clarksville newspaper and wrote about the bloodstains that shattered Mayberry, or something like that. I cried inside and in prose.

Scott Wise working on the clay form for the statue of Bill Longhurst, which will be unveiled Saturday. Longhurst’s son was used as a model for the statue. Wise also used old photos.

-- Photograph Provided“Dad really liked that column,” Russ recalls. “He liked that you called Guthrie ‘Mayberry.’

“I think that’s how he saw it, too: Mayberry.”

In the years since, whenever I’d poke my head into Longhurst General Store, I’d be greeted by a hearty smile and “Welcome to Mayberry” from Bill, who, if he didn’t need them, kept his eyeglasses on the counter near the register. Hated wearing them, which is part of the reason why the statue is of him at around age 50, pre-spectacles.

As my life became centered in Nashville, I didn’t go as frequently up there, but I called to check in.

“Things are going all right up here in Mayberry,” Bill would say. Then we’d talk of friends who preceded him into the Highland Cemetery where Robert Penn – that’s how the great poet laureate, scholar and author is referred to in his hometown, even to this day – had a stone placed in the Warren family plot, even though he was buried in Willis Cemetery in the Green Mountain National Forest, near his writing studio in Stratton, Vermont.

“I was probably in and out of his store most every day,” says Mack, the retired Nashville banker whose father was Guthrie City Judge Mack Sr. “Bill was a good friend. Bill and I were working on projects together.

“We had to argue about Vanderbilt (Mack’s and Robert Penn’s alma mater) and Kentucky basketball,” he says with a laugh. “But other than that, we got on well.”

The projects the duo worked on involved Guthrie Partners for Main Street, the nonprofit housed in an old mercantile building (that one day will be a transportation museum) on Ewing.

“It was a love of Guthrie as much as anything else,” says Mack, talking about his pal’s motivations for keeping the store going and for volunteering so much of his time to the nonprofit downtown revitalization program.

“We all miss it a lot,” he says of the store. But they miss Bill even more. “Bill did so much good for people, a lot more than people knew.

“He just did it quietly. He didn’t want to take a lot of credit for much of anything. He worked behind the scenes and did a lot.”

He says his friend “didn’t want anything named for him,” so he may have put up a fuss that the new downtown park, which he saw being completed, was named for him after his death.

“Mr. Bill served on our board of directors for 16 of the 17 years we’ve been in existence,” says Tracy Robinson, executive director of the Guthrie Partners for Main Street.

“He was aware of the pocket park” in the open lot next to Boogie’s hardware store. “He was serving as our board president when we decided to do it.” It hadn’t been named yet when he died.

“Then, in March, he passed away. It was a shock to all of us who were on the board,” she continues. “He was a dear, dear friend to me.”

If her job became frustrating “and I wanted to run in the other direction,” Bill provided her a shoulder and encouraging words. Like he did to almost anyone he met.

“We referred to him as ‘Mr. Guthrie,’” she says, noting that Bill was instrumental in the annual reenactment of “The Great Guthrie Mail Robbery,” which when it really occurred in 1938 was the largest mail robbery (the bad guys were after $25,000) in U.S. history.

Boogie played one of the bad guys in the reenactment that was organized and directed by Bill and was the anchor event of annual Guthrie Heritage Days.

“They shot me in the end,” recalls Boogie of the blazing-gunfire battle on Ewing, between his hardware and Longhurst General Store. That reenactment no longer takes place.

Scott Wise, the sculptor whose work will be unveiled Saturday, said he began the statue in June 2018 after it was commissioned by the Main Street group and paid for by Bill’s friends’ donations.

His models for the sculpture included Bill’s son, Russ, sitting down “and I looked at pictures from that time-frame.”

Scott, who is a Clarksville firefighter, is a distinguished sculptor, as well. And he wanted to get to the heart of the man.

“Tracy was a big help,” he says. “And I got to talk to his son and a few other people in the community. I got to know about his life somewhat ... A lot of people call him ‘Mr. Guthrie,’ and I wanted to make sure the family approved it before it went to bronze. They saw it in clay, and I wanted them to see it conveyed the feeling of him. That part was a little pressure, since I’m a stickler for detail, anyway.”

Forty-plus years ago, when I first met Bill and his dad, I was in the small Kentucky town to meet Louis Buckley, the longtime Nashville record retailer.

Mr. Buckley generally commuted down U.S. 41 to his work in Nashville, where he not only sold records but serviced jukeboxes, even in “fancy houses,” and ran a thriving mail-order record business, peddling his rhythm and blues wares on late-night WLAC.

After one of his clerks was stabbed to death at Buckley’s Records on Church Street in Nashville, Mr. Buckley packed up his records and hauled them back to Guthrie, where for a while they filled several storefronts.

He and his wife were early and often advocates for the still-thriving Guthrie Senior Citizens Center, right next to Longhurst General Store.

He was sort of the “emcee” of Ewing Street back then, and he introduced me to many people, including a fellow who pedaled his bicycle to Guthrie and decided to live in a lean-to near the old car wash.

Mr. Buckley died in 1985 after a long battle with colon cancer, and I still miss him, but I thank him for making me first feel that Guthrie was a second home, a place to come to in times of stress. I also am grateful for the hundreds of albums, from Jelly Roll Morton to Louis Armstrong, he gave me. Satchmo’s scratchy 78 rpm recording of “Song of the Islands” was the music played during his funeral.

I could go on about him, as I loved him as well and was a welcome guest in his home just outside town.

But, for this story, I must testify that the most valuable introductions he made were to Bill and his dad, the guys who ran the only thriving business downtown back then, a tradition Bill carried forward after his dad died.

A tradition that will be celebrated at 3 p.m. Saturday when the statue is unveiled, when Bill’s bronzed gaze will look toward his store on Ewing Street.

“I think he would have been very pleased,” says Mack, guessing at his old friend’s reaction to having a statue, a monument to the goodness that is Guthrie, really, staring from Longhurst Park. “He wouldn’t be admitting it to a lot of people. But he would be pleased.”

Russ Longhurst agrees with his dad’s best friend. “It represents his life and what he tried to do for the downtown community.

“He’ll be looking out over downtown. It represents his vision for downtown, his idea that ‘it’s great to be in Guthrie whether you are doing something or nothing at all.’”

Mr. Guthrie forever will be home.