VOL. 43 | NO. 41 | Friday, October 11, 2019

Nashville needs to own up to its past role in slavery

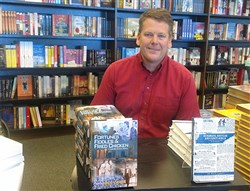

Author Bill Carey has written two books on Tennessee history. His first, “Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken,” examines the evolution of Nashville business.

-- Photograph By Tim GhianniNashvillians may not like to hear it, but just as the city is a celebrated crossroads for transport of goods and services via railroad, long-haul truck and airplane today, the place now acclaimed as Music City once was an “It City’’ for the slave trade … And it’s time to fess up.

That’s more or less the point Bill Carey, a reporter-turned-archive-miner and nonprofit-online-history educator, demonstrates in his book “Runaways, Coffles and Fancy Girls: A History of Slavery in Tennessee.”

“I remember telling (former Mayor) Bill Purcell that part of the job of the mayor of Nashville was to oversee runaway slave ads,” says Bill, adding that he told the same thing to David Briley.

And he no doubt will be telling Mayor John Cooper that his long-ago predecessors tended to the slave ads for the city.

Of course slavery, at least in its cruel antebellum form, is nonexistent in Tennessee now. There are parts of town where “fancy girls” still operate, and slavery does exist there, sadly. But it is not like slavery of the Old South, with people being bought, sold, rented out, traded and whipped for profit and as demonstrations of white supremacy.

There’s a certain urgency in Bill’s telling of this tale while he can and when people might pay attention, while the past still matters as Nashville sandblasts and detonates its warts-and-all history to become a homogenous “big” American City, a mirror of, say, Cincinnati or Indianapolis … except for the fact that slaves were bought and sold here until a war ended the process.

While the book explores, in detailed, almost laundry-list fashion, the history of the slave trade statewide – with a heavy dose on cruelty here from one of the It City’s frontier heroes – there are more complex reasons for the writing, long conversations with the author reveal.

“I’ve gotten a little bit irritated,” Bill says. “There was a story in The New York Times about Nashville coming to terms with its slave past.

“That is not true,” he almost spits, adding “the ownership of slaves is not something I discovered. But the fact that a slave died in the construction of the state Capitol is new.

“And I don’t think anyone had discovered it was illegal to write any law opposed to slavery. (And) If you wrote an Op-Ed piece against slavery in 1850, you’d go to jail. We were a slave state, and to say we were not is wrong.”

The point about the newspaper Op-Ed piece comes from Bill’s primary source of information in putting together this book: Archived copies of newspapers from across the state.

“I think slavery-related advertising was the second-largest type of advertising” in the mostly four-page weeklies that were printed in Nashville and the Volunteer State before the Civil War, he says.

“No. 1 were small retailers, like the local druggist. No. 2 wasn’t books. It wasn’t whiskey. It was slavery.”

“Valuable Negroes for Sale,” hollers one ad from the May 5, 1857, edition of the Memphis Daily Appeal. “THIRTY NEGROES just arrived from Kentucky and Virginia, among the number three good Mechanics.”

The advertiser in this case – many of the advertisements are anonymous and done with the newspaper basically as the agent, making sure interested parties hooked up – is “N.B. Forrest.”

Nathan Bedford Forrest, celebrated by a bust in our state Capitol building, by a private Hamburglar-like cartoon statue along Interstate 65, not far from my house, was a big-time slave trader in the years before the Civil War, after which it’s generally said he became the first Imperial Lizard of the Ku Klux Klan.

Actually, I guess it’s Grand Wizard, but I’ve had enough dealings with this vile, hateful scum in my newspaper life that they all are lizards to me. Probably libeling lizards here.

Nate – who I’d call The Lizard King, but Jim Morrison owns that title in the minds of Boomers – was the well-publicized focus of a Bluff City tussle over whether to remove the statue and the remains of the general and his wife from a public park.

The 1800s-era newspaper in Memphis, by the way, didn’t just make money from dollars for runaway-slaves and good-slaves-for-sale-or-rent advertisements. There was outright editorial support for the inhuman trade.

In his book, Bill points out that a story in the Memphis Appeal at the time noted, among other of his wares, Forrest had seven African slaves “directly from Congo,” who were different from “the generality of our homebred and hometrained negroes … One or two of them can say a very few English words, but all can use some pretty expressive pantomime. ...”

And ol’ Nate was not even the most brutal offender, at least according to the ads Bill mined from throughout the state.

One such slaveholder is a beloved Tennessean, war of 1812 hero and the guy who oversaw the stealing of Native American lands and forcing the occupants on the road to nowhere and death, the so-called “Trail of Tears,” thanks to the Indian Removal Act.

Talking here, of course, about Andrew Jackson, our seventh president, aka Old Hickory, King Andrew, the Hero of New Orleans, the guy the Creek called Sharp Knife because of his killing of Indians.

The Cherokee were more to the point, labeling him “Indian Killer,” online history sources reveal.

Of course, Andy’s estate – The Hermitage – is peddled as a top tourist attraction and offers a great look at upscale life in Middle Tennessee back then. It’s also namesake for the Nashville suburb it occupies.

How heroic was this “great” Tennessean, so admired by the current occupant of the Oval Office?

The Oct. 3, 1804, edition of Tennessee Gazette contained the future president’s most famous “runaway slave ad.”

Published at about the time Old Hickory bought the land for The Hermitage, he was whipping post-miffed about the escapee.

“Stop the Runaway” is the “headline” placed on the advertisement that goes on to offer a $50 reward for the return of “a Mulatto Man Slave, about thirty years old, six feet and an inch high, stout made and active, talks sensible, stoops in his walk, and has a remarkable large foot, broad across the root of the toes …”

Jackson warns that the slave could pass for a free man – “he has obtained by some means certificates as such” – and that he was bound for Detroit, which Bill says likely means the man was headed for the location of his family.

This ad is similar in style to most of the ads that pepper Bill’s book, and all are worth reading. Old Hickory accomplished much in his life, but apparently wasn’t celebrated for his humanity, as evidenced by the last part of the advertisement: “If taken out of the state, the above reward, and all reasonable expenses paid – and ten dollars extra, for every hundred lashes any person will give him, to the amount of three hundred.”

“In the more than 1,200 runaway slave ads I found in Tennessee newspapers for this book, this is the only one in which the slaveholder offered a financial incentive for the beating of the slave,” Bill writes.

Should note here that on the page in the book that faces the reproduction of that ad by King Andrew is an ad purchased by John Overton and appearing in the June 23, 1847, Republican Banner.

This is not the original John Overton of Travellers Rest, Nashville’s John Overton Comprehensive High School or Memphis’ Overton Park fame, the same guy who roomed with Jackson and counseled him on his marriage to Rachel, who was a divorcee.

Since that Overton, the Memphis park founder, died in 1833, the advertiser had to be either a son or a nephew. The ad seeks the return of Foster and Haywood, who escaped “five miles from Nashville on the Franklin Turnpike” (pretty close to Travellers Rest).

“The former is of dark complexion, about five feet nine or ten inches high, rather slender, and has a thin face – he is a quick-spoken and very smart and active boy, aged about nineteen years. The latter, Haywood, is of dark-yellow complexion, about five feet eight or nine inches high, rather slow to speak, has a full face and is aged about eighteen years. I will give $20 for the apprehension of either of them.”

There’s also the story of the double life of President James K. Polk, who “purchased two or three slaves a year for his different plantations,” Bill adds. “By the time of his death, James K. Polk (buried for now, at least, on the grounds of our state Capitol) owned 40 or 50 slaves. Whenever his slaves ran away, he had other people take care of the ads.

“You can’t find ads with his name on it, but they were his ads.

“One of his slaves ran away, and after they brought him back, he was sold down river, never to be heard from again.”

“Down river” generally means the flourishing slave-trade town of New Orleans, which does a better job of “selling” itself as the birthplace of the blues, jazz and Mardi Gras than as one of the great slave marketplaces.

I visit New Orleans fairly frequently. However, the only time I ever was told by a guide about the slave trade was over in Algiers. Just outside Mardi Gras World – a mammoth warehouse that houses floats and figures for the annual celebration – is a spit of land along the Mighty Mississippi that was a slave-holding place, a warehouse of sorts, where the captive souls were corralled before going across the river to the market.

The slave trade took place throughout New Orleans, according to that city’s historic site. However, the main market was in the French Quarter, where nowadays the saints go marching in on liquor-soaked nights filled with tourist hijinks.

Polk – remember the state and the Polk homeplace in Columbia have squabbled over his and his wife’s remains – is an example of how success was built in the Old South, Bill says.

“One of the things the Polk story does is bring to life that the way a person built wealth in the South before the Civil War was to buy and sell slaves. There weren’t really a lot of other options for building wealth,” he points out.

He’s not making excuses. He’s just explaining one of the key elements a reader takes away from the book that was seeded when Bill was looking for an installment in the history column he regularly writes for Tennessee magazine.

“I went down to the state library. I was in search of a column. I thought I’d write a column about the first issue of the long-dead Knoxville Gazette (purportedly the state’s first newspaper).

“I thought I’d read the whole thing, ads and everything else,” he says. “I didn’t think there would be slavery ads.”

He simply hadn’t thought about that possibility, until he was stared in the face by ads for “Runaway Negroes” and the like.

“Then I started looking at the slavery ads,” he says. “There were slavery ads in 1792. I went through 10 years of newspapers and found 15 or 20 slavery ads.”

The idea of limiting the topic to a single column vanished for the journalist/historian whose previous book “Fortunes, Fiddles and Fried Chicken: A Business History of Nashville” had been something of a local success, particularly in the business community he had covered as a journalist.

“I kinda got carried away,” he says, laughing a bit at himself and his understatement. “I figured I’d look at every paper I could find printed in the state before 1863 (when Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation) and find every slavery advertisement.

“I was discovering things in these ads that I didn’t know,” he explains, adding that he figured most people probably wouldn’t know those things either.

He began piecing together the drama hinted at in the ads.

“The ad might say that the slave is heading for Maryland. That tells you they have been split up (by the slave traders and owners) and that they are heading to see family,” says Bill, adding that while, certainly there were slaves in Maryland, most of the slaves came here from Virginia.

While immersed in the research, Bill hit some snags, in that there are major Tennessee cities – “Shelbyville was as big as Nashville” back then – with virtually no newspapers to examine.

“But there was a treasure trove of early Jackson, Tennessee, newspapers” and, of course Memphis and Nashville were represented.

“I do remember that it could be very confusing at the state library, because there may be things buried on unmarked microfilm.”

He cites the fact that after he found one edition of an early Murfreesboro newspaper, there was a 10-year gap between that and the next one he found.

“It was kind of like piecing together the Dead Sea Scrolls. I’m sure there is something I’ve missed. And my numbers are not necessarily conclusive.”

He did find a pattern that ads for runaway slaves were published between four and six times, “so if you look at an issue on Jan. 3 and then jump ahead to Feb. 5, you aren’t going to miss anything.

“Runaway slave ads ran for three months at a time,” Bill says, adding that same ad would appear in different newspapers.

The 53-year-old said that his search for that first planned magazine column began in October 2017, and he did write about that topic … but the story he found was so much more complex and couldn’t be told in a single published article.

“It was pretty obvious to me, I recognized that there is so much you can write about slavery in a column before people want you to do something else.”

He needed to move on, look for another way to get his research and the colorful, troubling portrait of Tennessee slavery to the public.

“I decided I was writing a book by the first of December and I was done in April,” he continues. “I move through projects as fast as I can, that’s how I get them done in my life.”

Illustrating the book was another issue. “There are practically no photographs of slaves who lived in Tennessee before they were free. If there are any, there are very few.”

Some photos had been taken during the advance of the Union Army, but not many. Other pictures exist of freed slaves.

“You can find pictures in the 1870s and ’80s of people who were slaves, but when a slave coffle (a group chained together, marching from one sale destination to another) came through downtown Nashville, they weren’t setting up the newspaper camera to take pictures of it.”

He notes “there is a very famous picture taken in the 1880s of former slaves in front of the Belle Meade mansion, but the people were old” and freed, and that wasn’t the story he was telling.

He decided the newspapers, with their ads and occasional stories, would provide the illustrations that in themselves sometimes tell full stories in the book that’s available at some local stores and through Clearbrook Press.

The project is noteworthy in that it shows a side of life not really celebrated in the tour guides to our bustling “It City.”

And sometimes “truths” are untrue.

“At a house across the street from the downtown arena, a privately placed marker claims this house was a well-known stop on the underground railroad. Well, there were no well-known stops on the underground railroad” (or it wouldn’t have been underground, of course), Bill says.

“That marker now is the tourist draw to what is now a Mexican restaurant Pancho and Lefty’s Cantina,” near Fifth and Broad, where visitors “Talk. Laugh. Love. Eat Tacos. Dance.”

While there isn’t much evidence circulated by the tourism officials who run our city, Bill says his research shows that Nashville was “a slavery city (on the same scale as Memphis and Charleston). We had a very active slave trade.”

I interrupt Bill to ask a bit about what he’s doing now that he’s not chasing down slave stories and ads or speaking to groups interested in the subject.

In 2004, after he left the newspaper business (stops in Nashville at the morning newspaper and in Knoxville), he started a nonprofit called Tennessee History for children.

“I had found the niche that I didn’t think has quite been met,” he explains. “Public schoolteachers didn’t have a real good resource that covered Tennessee and local history at the grade level they needed to.”

He provided what he says is the answer via his free website tnhistoryforkids.org, as well as in the booklets he writes and sells to offset costs.

Through sponsorships and booklet sales, he’s able to achieve his mission of helping to make history relevant to schoolchildren.

It’s sort of like what he has done in his book: Take a slice of Tennessee history – the slave trade – and write about it, try to make it relevant and revelatory to readers.

“The one thing I came away with. It may have taken a month’s work to sink it: A lot of people say the Civil War was about more than slavery.

“But the wealthiest one-fourth of Tennessee owned slaves. The newspapers, the banks, chancery court judges and institutions were pro slavery. Factories and railroads hired slaves (from slaveholders) to keep their costs down,” he says by way of stating just what was the key reason for going to war with Mr. Lincoln and the abolitionist states.

“Can you imagine a world in which all seven or eight of those groups are in favor of something (and the rest of the country opposes it) and we didn’t have a war over it?”

Again, he points to the newspapers across Tennessee – his research resource – and their boosting of slavery for the sake of revenue and to appeal to their lowest common denominator (at least in terms of humanity) readership.

“Newspapers were bitter foes of abolitionists … Before the war, these people are defending their largest advertisers.”