VOL. 43 | NO. 28 | Friday, July 12, 2019

‘Roadhouse Rambler’ gets late start on country dream

Mike Cullison, a retired telephone company employee and a self-professed lifelong poet, is pursuing his modest dream of writing songs and performing for appreciative fans. “I’m not going to make millions, be a big star. Just pay the rent.”

-- Photograph By Studyvin Photography ProvidedThe Roadhouse Rambler – a guitar leaning against the nearest wall – looks across the kitchen table in the tidy home his phone company career helped buy. His smiling eyes wander back to dusty Oklahoma.

“When I was growing up in Shawnee, Oklahoma, every boy wanted to be either Elvis or Mickey Mantle,” he says, confession punctuated by the barking of Maya, the 7-year-old Black Lab-Bassett mix that “Mr. Rambler” – which is how I addressed him after tracking down his phone number – and his wife, Dianna, rescued.

“Never been without a dog,” says Mike Cullison, aka The Roadhouse Rambler, who at “almost 70” has likely given up the dream of being “The Mick,” either because he can’t switch-hit or because he’s just too damn old.

Every boy born in Oklahoma in 1949 wanted to be like The Commerce Comet, the great Yankees slugger who was given that nickname because of the Oklahoma small town where he grew up, where the legend was nurtured. (I’ll note here that The Commerce Comet actually was born in Spavinaw, Oklahoma, so he could have been The Spavinaw Slugger if headline writers had reached back that far.)

While Mike never matched homers with Roger Maris, his pursuit of “being like Elvis” – while still and forever illusive – continues to guide his singing-songwriting life, seeded in an Oklahoma kitchen, but thriving now as his full-time pursuit after leaving the phone company chores behind a decade and a half ago.

“I always sang, since I was a kid. Mom and her sisters would sing hymns on Sundays while they were in the kitchen, and they got us kids to sing along,” explains Mike, warmly drifting into the deep and happy past where the root of his musical passion was planted, acapella style.

In addition to the relatives singing over the smell of frying chicken, the radio was always on in the home and cars of his parents – road construction worker dad, Jim and mom, Betty, who worked at Woolworth’s in Shawnee and later at Tinker Air Force Base after the family moved to the Oklahoma City suburbs.

“My dad always kept it on the country station, especially when we were driving anywhere,” says Mike, running his fingers over his white Fu Manchu mustache and still-sprouting (“I’m too lazy to shave sometimes”) chin whiskers.

“Mom liked rock ‘n’ roll more. I remember she bought me the ‘Blue Hawaii’ album by Elvis.” I smile at Mike as I remember my own purchase of that album, my first LP, when I was 9. Up until then, I’d loaded up my record collection with 45s I purchased for a nickel apiece from the son of a barkeep who gave his kid the old records after replacing them in the jukebox.

Mike nods when I mention those records and the singers. “I grew up in the ‘50s, so Elvis, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly, Carl Perkins, I liked all those guys.

“But wasn’t a boy back then who didn’t want to be Elvis. He was The King.” Still is, of course, dead or alive.

There was good rockin’ in the Cullison household, but there also were gently weeping steel guitars and blue yodels, yielding a concoction that informs the mostly country – with doses of Van Morrison, Buffett and The Beatles – music that keeps Mike rambling from roadhouse to roadhouse, with stops at cheap dives, nursing homes, upscale joints and house parties punctuating that journey.

Being like Elvis remains a great guidepost. But knowing Hank done it this way also is a part of the allure of his lifestyle.

“I always have liked country music, too. My parents would always watch those country television shows with the Wilburn Brothers, Buck and Porter, those kind of shows. And I got indoctrinated, too. And there were some locally produced shows, too. The stars, like Merle (Haggard), would drop in on them and play when they were in town or passing through.”

If he sang along it was simple, light acapella emulation of what he was seeing on the black-and-white Emerson or whatever. “You couldn’t keep me shut,” he adds, with a laugh.

“I never was disciplined enough to learn how to sit down and play the guitar until I was in my 30s.”

It was simply his voice that he used to accompany Buddy, Hank, Cash, Merle, even The Beatles and The Rolling Stones. “In high school I’d get in the car with the radio on, and I always was singing whatever was popular at the time” as he drove around Midwest City, Oklahoma, the OKC suburb where his parents had relocated the family following the Shawnee years.

“I went to my 50th Midwest City High School, class of 1968, reunion last year. One guy said he remembered that I always sang when I was in the car. I really didn’t remember that, but that’s the way I was remembered.” He shrugs.

Mike put his singing to good use during that gathering of baby boomer relics chasing their forever-dead youth as proud Midwest City Bombers.

“I did a gig there, and they liked it. They asked me to come back, so I guess I did OK.”

Someday, he reckons, he’ll return to Midwest City for that encore.

Even while he wasn’t composing melodies in his pre-guitar days, he was writing songs because he could “see” the lyrics, their rhythms and cadence in his head.

“I was a poet forever, even as a kid,” he explains. “Poetry captured my mind, that’s what it did. So that’s what I did, write poems. That led to writing lyrics. And that led to where I’m at right now.

“I began songwriting in my late 20s, but I still didn’t know how to play guitar. I had a real good guitar, still got it here, but I didn’t take the time to learn it.”

He knew he wanted to be a professional songwriter. He also knew he was holding himself back by not being able to compose melodies on an instrument.

That “real good guitar” needed to come out of the closet.

“Right after Dianna and I got married (in 1983), I said ‘I’m either going to learn how to play this guitar or I’m going to get rid of it.’

“So, I started teaching myself songs I knew the melody of.” He says this worked, because he could tell when he missed the melody, and he could keep picking until he hit the sounds to match the music in his head.

“I got addicted to playing the guitar,” he acknowledges, noting he always kept it in reach even if he was watching TV, just in case Crockett and Tubbs, Daisy Duke, Columbo or J.R. Ewing inspired him to play along.

Finally gaining confidence, “I said ‘I can do this,’ and – with my guitar – I went from entertaining relatives in the backyard to graduating up and working in bars.”

Of course, he kept up his work with the phone company. Most musicians I know have “straight” jobs of some sort. But he made songwriting pilgrimages to Music City from Oklahoma City and then from Atlanta before his phone company career finally brought him to Nashville.

“When I started at the phone company, you did everything,” he says, pondering the solid career that led him to the city of his dreams, this songwriter’s Oz.

Sometimes that phone company career had him climbing a creosote-smothered pole to fix a line, other times it took him into homes and businesses. (I really wanted to refer to him as a “lineman” in this column, because of the classic country connotations, but his job wasn’t always up in the air or on the main road.)

“That was back in the days when if people had trouble with their phone, they’d just call the phone company, and we’d have to go out and fix it or replace it. That meant we went wherever we needed to go and do whatever we needed to do.

“I worked the last three or four years inside the Batman Building,” he adds. “It was an inside job, with computers. We took care of special clients, whatever the term was. Took care of their electronic switches.

“It was a lot of studying, keeping up with the changes. It was very interesting work. It also was tedious.”

He decided in 2004 that “it was time to make a move” to do what he really wanted to do for a living: Write songs and perform them if he could.

With the backing of Dianna, who he met at the phone company – “she was a Texan, but I married her anyway”– but who now works in information technology at Vanderbilt Medical Center, he made the early retirement leap. (By the way, he notes that the marriage to Dianna is working out just fine after all these years. “I’m happy with it. And she keeps coming back after work every day.”)

“I’d had enough years with them (the phone company, under its various monikers) to retire, and they were only taking a certain number, but I made the cut to retire.”

He admits to some apprehension at that final departure from the Batman Building. After all, it had been good, steady work for him ever since finishing his 1968-71 stint in the Army (“I was lucky I didn’t have to go to Vietnam”) right after high school.

Seduced by the guitars in his Inglewood home and the musical poems he had written, he was swapping corporate stability for the uncertain life of a musician.

“I had to be ready in a way to leap out there and start flying on my own. It was: ‘Swallow hard and go.’

“But I knew this is the way I wanted to go. This was the best plan of action.”

He laughs and lifts up a yellow legal pad filled with scrawled black ink when I ask him if the high-tech ways he learned at the phone company have transferred into his songwriting world.

“No, I don’t use a computer,” he says, lifting the pen and tapping the top of his head. “I just hook up this (the pen) to this (his brain).”

He does, however, employ slight technology by pounding the finished product into his iPad, where he groups lyrics and set lists that he can call upon whether he’s playing in a bar by himself or with his band, The Lucky Dogs. “We’re just a bunch of old farts who get to go out there and play,” he says. “We’re having the time of our lives.”

He demonstrates that the set lists are indexed for particular clients. “This one is for Richard’s in Whites Creek, and all he wants is original stuff.”

Other lists include, for example, a mix of his own compositions as well as stuff like Van Morrison’s “Brown-Eyed Girl” and The Everly’s “Bye Bye Love.”

“Those are ‘tip’ songs,” he says of the chestnuts that he sneaks into his mostly country sets.

“There’s this girl out there at Dale Hollow where I play who always requests ‘Brown-Eyed Girl’ three or four times,” he says, laughing. When the customer is paying for it, you give him or her what’s requested.

So, ringing the mental cash register, he sings “Sha la la la la la la la la la la dee dah. Just like that.”

At least she’s not requesting “Free Bird” three or four times as the barroom night turns to misty morning fog for Mike and The Lucky Dogs. That band, by the way, includes Michael Ross on lead guitar, Bryant Keith on mandolin and guitar, Chuck Gillihan on bass and Bobby Kent on drums. Mike, the bandleader, plays rhythm and sings.

“I get told I have a good voice,” he continues when asked how well his voice holds up now after beginning his singing career with those Sunday afternoon fried chicken revivals with his mom and aunts in the Shawnee kitchen.

“When someone says that my voice is good, I thank the people and move on. I don’t have a big head about it.”

The largest number of the songs he sings are those he has composed or co-composed in writing sessions. On this very afternoon, he waits for a phone call from a young woman songwriter from Wales who wants to organize a session together.

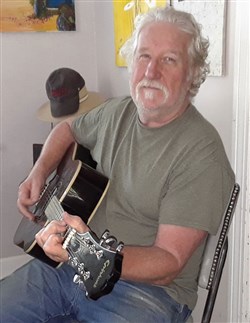

Mike Cullison, sometimes known as “The Roadhouse Rambler,” taught himself to play the guitar by picking along with melodies he knew or heard on radio or television.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The Ledger“I’ve written or co-written 200 or 300 songs. Self-published. I’d like to have a publisher, but I’m afraid I’d get stuck in a room writing songs with someone I can’t trust. I like co-writing, but I like making sure it’s with someone I trust. It makes it a lot easier, because sometimes during these sessions you aren’t writing a song, you are just talking.” Honest, semi-private chatter that may lead to songs.

He does two or three writing sessions a week and, of course, rolls those songs out while he is singing songs by some of his favorites, from rock to country to a mix, according to the crowd and likely the liquor level.

“When I’m singing, I do anything from Hank Williams Sr., who’s the best, to maybe some Delbert McClinton blues-rock. And rockabilly, like the music I grew up with: Elvis, Carl Perkins, all those guys.

“The best part of it is meeting people and being able to travel,” he says of this life he has chosen. “Get to Europe, maybe three or four times in the last four years.”

Mike particularly likes to play in Northern Italy; he has friends in the Florence area who help set up gigs and house parties. He’s also performed in Germany, England, Scotland, France and Spain.

“If I’m going to travel, I like to travel to Europe after all these years of traveling to play in West Texas or Southeast Texas. Oh, I’ll still travel there to work, but I prefer going to Europe.”

Like so many Nashville Cats who play for room, board and Euros, he doesn’t get rich on those swings. He just meets people and learns stuff and enjoys life.

“What we make over there doesn’t really cover the cost of flying over there, but it takes care of all of our expenses while we’re there. I’d stay in Northern Italy if I could. Something special about those people. They are real friendly and family-oriented.” He’s going there again in October.

About once a month he plays for the residents in the Celina Rehabilitation Center. While up in Clay County for that nursing home gig that pays him “enough for a tank of gas and lunch,” he also visits with his older brother, Andy, his sole sibling. That retired printer lives in a house Mike and Dianna bought as an investment.

When Mike disappears into his Inglewood house to secure a couple of CDs – “Barstool Monologues” and “Roadhouse Rambler” – I notice the lifestyle-mantra signs hanging over the kitchen counter: “Eat Less. Lose Weight. Don’t Drink. Die Anyway.”

“I got songs for everybody,” he says, when he returns and offers up the two albums. “Happy, sad, boozers, losers, winners” all can seek comfort and discover self-identity in his works.

He picks up the guitar near the kitchen table and settles it in his lap.

“I get up in the morning and have a cup of coffee and say ‘OK. Let’s go.’

“Then I give myself an hour, two hours to write,” he says, taking a long draw on a glass of diet Dr. Pepper.

After that, well there are songwriting sessions and rehearsals with The Lucky Dogs. Or perhaps he is “out networking” in the music community where he has yet to earn his big break, but says he still might. Anything’s possible.

“The rest of the day, I do ‘Honey-dos and honey-don’ts,’ be a good househusband. Cook. I like to make breakfast, because it’s the easiest for me.” But dinner is also generally ready when Dianna gets home from her IT job.

I notice, on inspection, that the scrawling on the top page of the legal pad on this day is not one of his works in progress. Instead it’s a nifty little song by some world-acclaimed musical artists. He’s adding to his Lucky Dogs’ set list.

“This is a Beatles song, ‘You Can’t Do That,’” he says. “It’s an easy song, C, F and G. Everybody knows The Beatles.” He knows he and the Dogs will neither let audiences down nor leave them flat with this classic rocker by jealous guy John Lennon and his mates.

That song choice pretty much illustrates the fact that while Mike’s songs are primarily country with occasional doses of pop, rock or rockabilly, there is one songwriter who is beyond peer, a guy whose precision and passion he hopes he can match.

And it’s not Hank Williams.

“My absolute favorite songwriter is John Lennon,” Mike says. “It’s his honesty, passion, the way he writes, the depth of his songs.

“Like ‘In My Life,’ that’s the greatest love song. No one could say it any better. As a songwriter, I strive for that.

“As I tell my band, you can write about love and hate, but you gotta say it in a way that hasn’t been said before if it’s gonna affect people.” Lennon, he adds, reached a level beyond parallel. I reassure him he’s right.

Our conversation again travels back to Oklahoma, where he began singing over frying chicken, where he taught himself the guitar, where he got married and began his career as a lineman and more.

Mike’s proud of his heritage and points out that there are some Sooners who have done OK in country music.

“I got to see Vince Gill when he was a kid. He was playing with Mountain Smoke (Oklahoma City folk-bluegrass outfit). They were sneaking him into bars back then so he could play.

“He was excellent. People like that you hear them perform and you say: ‘THAT’S THE GUY!’

“I also saw Reba McEntire when she was performing before the bull-riding began in Ardmore, Oklahoma. I said then that somebody was going to take her away and she’d be a big star.”

Mike will turn 70 in November. And he still is pushing himself, dreaming that this isn’t all there is.

“As a writer, I think my songs are as good as anybody’s. I do what I do, and I consider myself an artist in the art of writing songs.

“I have a lot of songs that now are still bits and pieces, barely brush strokes. Then I have some where the seascape isn’t finished or the mountains aren’t there yet.

“The songs are paintings to me.”

So far, those paintings are sung by him and The Lucky Dogs or simply solo in barrooms.

A few have been picked up by “B-level and C-level” country artists.

And, he maintains, his best lyrics haven’t yet made it from his brain to the pen to the yellow notepad of his compositions.

“I’m not going to make millions, be a big star. Just pay the rent.”

Those dreams of finishing up those brush strokes with brilliant lyrics and melody painting his masterpieces, are encouraged by Hank Williams, the elder, and, as he says, John Lennon.

But, “Elvis was the catalyst” when he began music-making and The King continues in that role today.

Even after all these years, Mike’s still doing what Elvis advised in his best movie-soundtrack song: A guy’s “gotta follow that dream, wherever that dream may lead.”

Mike, The Roadhouse Rambler, looks across the table as we discuss his music career. “I’m doing probably better than I anticipated, but not what I dreamed.”

But he’s not done following the muse nourished by singing hymns over frying chicken on precious Shawnee Sundays.

Maya, the Black Lab-Bassett Hound rescue, barks as she follows me out to my car. She sounds mean but she’s wagging her tail.