VOL. 43 | NO. 24 | Friday, June 14, 2019

The legends who made 'endangered' Music Row are gone

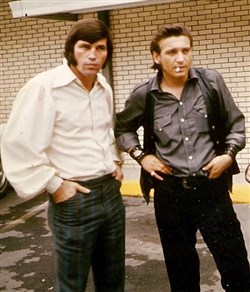

Billy Ray Reynolds, left, and his boss and pal Waylon Jennings grab a break in the alley behind RCA studios on Music Row. Jennings and Reynolds, his guitarist, were among the many famous characters who hung out and made hit records on Music Row.

-- Photograph ProvidedMore than a decade and a half ago I took a beloved poet, picker, prophet and pilgrim down to “Music City Row,” as he likes to refer to that stretch of Nashville. He hadn’t been there really for 30 years, and he lamented what he saw. Or didn’t see.

“I wish the old stuff was still here,” said Kris Kristofferson, who had helped construct the mythology of the old music-business district.

Now, after almost 16 more years of even more radical change, the arbiters of historic destruction finally are catching on and fighting to preserve what’s left of the little “music factory neighborhood” where Nashville’s image was built to the tune of gently weeping steel guitars, mandolins, pianos and their kin.

For our 2003 visit, Kris reminisced while retracing his steps and looking for something familiar, like the old Columbia building, where he had emptied ash trays for the likes of Johnny Cash and Bob Dylan to support himself while he was, in his “free” time, injecting his Oxford-educated poetic muse into songs he was writing in his nearby rundown apartment. But the doors to Columbia were locked that day. Nobody was “home” making music in Studio A or the Quonset Hut.

So, that building seemed like a perfect place for me to begin my “follow-up” exploration the other day.

My search for Music Row, that old neighborhood that now officially has been labeled “endangered” – but already is D.O.A. to many – led me up the stairs in that old Columbia studios building and to the middle of a room, where I sought out a specific spot in the floor.

Bob Dylan stood in this exact place inside Columbia Studio A, I told myself, mind’s-eye playing across what is now a sort of music classroom. Dylan looked from this spot to see Charlie McCoy on trumpet, Kenny Buttrey pounding his bass drum with a timpani mallet, Wayne Moss on bass, Pig Robbins on piano … all sorts of musical legends and hangers-on chiming in with instruments and voices, contributing a glorious ruckus to create what producer Bob Johnston conceptualized as something of an anarchic Salvation Army Band.

“They’ll stone you when you’re riding in your car. They’ll stone you when you’re playing your guitar,” sang perhaps the 20th century’s most-important musical voice. The studio shenanigans went extremely late into the night for “Rainy Day Women #12 & #35,” which became the opening track on Dylan’s ground-breaking “Blonde on Blonde,” rock’s first double-album and one that bred a four-album Nashville recording stint for the guy with that thin, wild mercury sound.

“Everybody must get stoned,” he hollered, and Dylan’s work here – and some of it does have country roots – played a major role in bringing even more recognition to Music Row as a recording capital.

I spent four days last week wandering the streets of Music Row – where I began hanging out back in 1972, when I was looking for Waylon and Willie and the boys. It isn’t unusual to find me still driving through here, but on these recent pedestrian tours, I was simply trying to determine the veracity of the official proclamation that Music Row is among the most-endangered neighborhoods, words that set off a panic (and little else) among preservationists.

These sirens signaling the apocalypse of the Row can’t be heard above the roar of bulldozers and other implements of destruction that are turning Chet Atkins’ old office, among other historic Music Row locales, into dust and gravel. Destruction and construction now create the jarring soundtrack above the same sidewalks where Kris long ago heard only echoes of silence and desolation:

“And there’s nothing short of dying

That’s half as lonesome as the sound

Of the sleeping city sidewalk

Sunday morning coming down….”

Nowhere in that song, made famous by Kris’ friend Cash, does my old friend talk about backhoes and excavators overpowering that lonesome sound while I witness the end of Chet Atkins’ office building. It was really more like a house, as was most of the architecture on Music Row for decades.

Just like every neighborhood in Nashville, there is no government authority holding speculators’ feet to the fire to try to match the existing architecture. Bland modern buildings and tall-skinnies create increasing anonymity.

Shortly after Chet’s death June 30, 2001, his widow Leona (since deceased), who knew how much I valued my relationship with her husband, gave me the hand-carved nameplate the great guitar picker, Music Row force and accomplished woodcarver had made for his desk in the now-vanished office. It’s in my office, next to a John Lennon “Give Peace A Chance” beer glass.

My visits to the Row in recent days were simply because I wanted to see this imperiled neighborhood for myself. I’d been trudging 16th, 17th and even 18th and 19th avenues south regularly for 47 years, but I wanted to check out, at pedestrian speeds, the “oh-woe-is-us” wailing.

Scores of buildings – the cottages that had been songwriting factories, recording studios and music exec offices – and even a famous old speakeasy – already are gone.

The bulldozing of Chet’s place and the adjoining three or four just adds to the casualty count that is the reason the National Trust for Historic Preservation – citing 50 demolitions in the last seven years – put the Row on a list of 11 Most Endangered Historic Places in the U.S.

As I walk along the Row, I see one of those tourist-hauling Joy Ride golf carts parked near the old Columbia complex – still bearing the Columbia and Decca names, but really now learning labs for Belmont University’s Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business. I ask the cart driver and tour director their thoughts on desolation row, since they make their livings keeping alive the myth and lore.

“I don’t think Music Row is as endangered as they say,” says Patrick Rolling, the tour director.

Golf cart driver Danielle Wannemacher scans Music Square East – or 16th Avenue South as I always called it when I was trying to become an outlaw without a guitar.

“This road seems pretty consistent with what it’s always been,” she says. “One block over (on former 17th Avenue South), you see the changes.”

I wonder if anyone attempting that high-speed circular merger around Nudica – aka “Musica” – ever slows down long enough to see the bronze statue of Nashville Sound architect Owen Bradley in the park named for him.

When I visit Owen’s bronze likeness, a pedal tavern filled with tourists singing that great country standard Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline” passes without pause.

When I first moved down here, one of Hank Williams’ supposed old houses was a “museum” on Demonbreun, near where the Nudica roundabout now greets the arrival of tourists. Nothing says country like statues of well-endowed naked people.

As she sits in the golf cart by Columbia, Danielle’s eyes focus on the artist publicity signs and the giant guitar installations – “if you ever want to talk to tourists, just wait by those guitars,” she recommends, noting those are favorite selfie locales.

Mammoth condominium buildings preside over what is now Music Square West, probably built by newcomers having nothing to do with music. These sleek modern buildings jutting toward the sky, shadowing and overshadowing the one or two-story houses where Music Row magic was invented, seem out of place. They’ll soon be the norm.

Mike Porter, the facilities manager, aka “the keeper” of the old historic Columbia building with its Studio A and the famed Quonset Hut, where Patsy Cline cut most of her hits for producer Owen Bradley, has worked on the Row for years. From his office, where he works with the Belmont students and faculty who use this space to learn, he can see across what I still call 16th to the SESAC Building and the Country Music Association HQ.

He says Music Row “probably is in danger” at least in terms of the architecture. “I don’t like seeing the old buildings coming down,” he says. “The big threat is: Are we losing the music business with all these condos being built?”

The high price of real estate here already has been a boon to Berry Hill, as studios, luthiers and related businesses move into cottages there that are similar in size to those that are disappearing from Music Row … and where a neighborhood feeling remains.

Mike says a particular sore spot has been the demolition “of the red Victorian that was torn down for the Virgin Hotel” at 17th (remember, I’m sticking with the numerals) and Demonbreun. “When they cleared that property, remember all the brouhaha?” he asks.

The anger that turned up on News 2 and its kin came after people realized the building was gone. Don’t look back.

“I miss it, because it was a thumbprint,” Mike adds. “In addition to that, there were trees there.”

If you’ve never seen a poem as lovely as a tree, well you’ll pretty much have to settle for poetry as you walk or drive past the condos.

Mike smiles, though, when he looks out his window at the SESAC building, noting that change is – good or bad – part of life, growth and architecture.

“Fifty years from now, people will be bemoaning the fact that SESAC went down” … to be replaced by a rocket-powered scooter company or whatever.

Outside the Columbia building – where Kris worked as a janitor to pay for his $50-a-month apartment, just above the Rev. Will Campbell’s, on 17th, I stop a pair of tourists who tell me they are from Goiania, Goias, Brazil.

Neile Leite and Sandra Rocha spent the night before on Lower Broadway, but on this day they decided to visit Music Row.

“Where do we find the music?” Neile asks. “Not here,” I reply, then recommend a few non-Broad places I favor when I rarely feel feisty.

My friendship with Kris was birthed near the former site of that apartment building back in 2003, not long after Johnny Cash died, when the singer, his son Johnny Cash, Kristofferson and I walked along Music Row. (Rev. Will – the activist, author, preacher and damn nice guy – always recalled Kris as a good neighbor, by the way.)

I documented some of the details of that “homecoming” trek with Kris in a column I wrote for The Tennessean. I don’t need to share that story here, but basically – as noted at the top of this column – he was surprised by what he didn’t see.

That apartment building was gone. So was the house by it, where Combine Music Publishing’s Bob Beckham operated. Back in the early 1970s, when I first moved to Nashville, Kristofferson’s phone number and address were in what we used to call “the phone book.”

I called the number, got no answer, but went down there to see who I could meet. I’ve always been a word man, better than a bird man, as Morrison said, so I admired Kristofferson’s recordings. Beckham kept the lights on in the front of his office, and Kris’ album covers were spot-lighted on the wall.

About a half-block away was The Tally Ho Tavern, a favored watering hole where Kris had worked as a barkeep (mostly for the free beer) in his early days in Nashville. Since he had featured it in one of my favorite songs – The Silver Tongued Devil and I – I became a Tally Ho semi-regular.

Musicians and songwriters filled the front of the bar and sat on the picnic tables out back in warm weather, working out their songs, laughing and drinking.

The Tally Ho was long gone by that afternoon in 2003, replaced by a Curb Music building of some sort. Kris and I looked at the spot where it had been and, arms over shoulders, we “harmonized” on that song: “I took myself down to the Tally Ho Tavern to buy me a bottle of beer. And I sat me down by a tender young maiden whose eyes were as dark as her hair …”

The point of bringing this up 16 years later is to note that change is nothing new on Music Row. And perhaps the character, the myth died with the Tally Ho or in the house across 16th, “The Professional Club,” a BYOB Music Row speakeasy where Merle Kilgore and Audrey Williams entertained everyone from Porter Wagoner to Kris, Funky Donnie Fritts, Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Cash and Waylon’s sidekick, guitarist and singer-songwriter Billy Ray Reynolds. It was a place where country musicians could drink in relative peace in pre-liquor-by-the-drink Nashville. Opry stars would trickle in after that show ended down at the Ryman.

“There’s a lot of memories. It’s hard to see. It’s changed so much,” Kris told me that day as new buildings had taken over the places where he lived the life he painted in his masterpieces.

Kris doesn’t do many interviews these days. Most of the rest of that old crowd – Waylon, Porter, Little Jimmy, Tubb, Kilgore – took the pre-demolition good old days to their graves.

But Billy Ray Reynolds is alive and reasonably well (he does take dialysis) in his hometown of Mount Olive, Mississippi.

“I’m two doors down from my great-grandmother’s house,” says the guy who spent more than 40 years in Nashville, much of it on the Row, where he knew every alley, studio, shortcut and bar – even though he didn’t drink. “Never had a taste for it,” he points out.

A guitarist for anyone who needed him, but really a fixture in Waylon’s band, he ran these musical streets with the best and the worst of them.

He retired to a quieter life in his hometown, but he still loves the Nashville of his memories and visits occasionally. His most recent visit was last year, when he and other members of Waylon’s band got together for a show at Bobby’s Idle Hour. That tavern was preparing to say farewell to 16th Avenue South, where in two different locations it had been a song-swapping, beer-soaked, smoke-filled reprobate of a hangout for pickers and writers. It’s closed now, to make way for new development.

A tour bus slows as it passes the old Columbia Studio A and Quonset Hut complex, known for its rich history of recording sessions by the likes of Bob Dylan (Studio A) and Patsy Cline (Quonset Hut). The historic studios on Music Square East (formerly 16th Avenue South) are now learning labs for Belmont University’s Curb College of Entertainment and Music Business. Kris Kristofferson began his music career while working as a janitor in the complex.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The LedgerNew owners – Thom “Lizard” Case no longer is involved – are planning to bring it back in another nearby location, but my efforts to talk to them or to get an answer at the door of the place that will house the new Idle Hour were unsuccessful.

But I did get Billy Ray, who begins the conversation by stating “Music Row is gone.”

Of course, it’s physically here and evolving, but the place of myth, of Hillbilly Central, of all-night pinball at Bobby Bare’s office is at the very least comatose. My friend Bare, not really a carouser, would leave Waylon and Captain Midnight to their games and go home to sleep while they rolled quarters into that bingo-like gambling machine or took breaks to have knife-throwing contests.

“We ran the blocks day and night,” says Billy Ray, 79, and still singing and recording. “I’d go home and get a nap and I couldn’t wait to get back to Music Row.

“We actually figured the beginning of Music Row was Lower Broadway. Demon’s Den. Linebaugh’s, Ernest Tubb Record Shop. Wagon Wheel. Tootsie’s,” Billy Ray adds. “Tootsie would close up at 3 a.m., and we’d go to Willie’s house in Ridgetop and jam until 8 or 9 a.m. We’d go wake Eddie Cochran up at 3 a.m. It was a different world.” A special fraternity.

The heart of their world was along 16th and 17th avenues south, spilling over onto 18th and 19th.

“I don’t go up there much anymore,” he says of Lower Broad and Nashville in general. “I got spooked when I was up there. It was so crowded. It’s like going to the World’s Fair. It’s all about the money now. And there’s nothing we can do about that, either.

“I knew all these people, and I loved them dearly,” he says as we talk about everyone from the Outlaws to the music execs to the Opry stars who found pleasure, business and cocktails on the Row.

“Back then, you could go into any session you wanted to go, not invited.” Who knew when a guy would be asked to add a guitar line or a rhyme?

“Back when we were touring, Waylon would tell me ‘Go out and do three or four songs and call me up.’ We had a great band. Then I’d see him over in the wings and I’d introduce him: I’d say ‘Now, ladies and gentlemen, meet the greatest singer in the world’ and Waylon would come out.”

Billy Ray grows solemn for a moment, recalling that after Waylon died in 2002, he physically helped carry the great singer to his gravesite and, before saying goodbye, he quietly repeated that same introduction across the lonesome Texas field, hoping God and the wind were listening.

Of course, most of his memories are not somber as he describes his version of Music Row.

“I pushed Bob Wills in his wheelchair for his last Nashville session,” says the singer-songwriter. “It was about 1969 or 1970. We recorded in a little studio next to the Quonset Hut. Kapp Records.”

It was something of a super session for the King of Western Swing. Johnny Gimble, D.J. Fontana, Dale Sellers, Jack Drake, Pete Drake and Shorty Lavender made up the band. Billy Ray says he was just there to hang out and to help if asked.

“I was a young and energetic old boy, and we got Bob out of the car and onto his wheelchair. He and I just laughed and joked,” he recalls, as if this occurred yesterday.

“I knew Virginia,” he says, happily when I bring up Virginia’s Market, over on 18th and Division. I’m sure Music Row types still visit the place, but back when Virginia was in charge, it was a destination for red-eyed country stars, Memphis Mafia members (if Elvis was working over at Studio B) and other musical types seeking biscuits, cold drinks, cigarettes and good company between pinball games, knife-throwing marathons and recording sessions.

“We called it the Murder Mart,” Billy Ray adds. “A really nice old boy worked there, and one night somebody came in to rob it and blew him away. That haunted me a long time.

“One day I was walking down to the Murder Mart to get me something. Had to pass Marty’s office on 18th. Marty (Robbins) was sitting there with his door open and he said ‘Hey, come here, come here, come here. Listen to the song I just wrote.’

Pedal taverns carry tourists through the Music Row area, its participants seemingly oblivious to the history of the neighborhood. This one didn’t slow as it passed Owen Bradley Park. Most of the passengers seemed to be eyeing the mammoth Musica statue in the roundabout at 16th Avenue North and Division.

-- Photo By Tim Ghianni |The Ledger“That was just a part of it back then on Music Row, the ability to have Marty Robbins want you to come in and analyze his songs. He’d always have his door open, playing the piano and writing. Marty was cool.”

As for the Professional Club, the speakeasy on 16th mentioned earlier: “Tompall (Glaser) and I was sitting at the table. George Jones. Faron. They were all drinkers. Waylon was in the other room shooting pool,” he says.

“The room was so private. Faron was an obnoxious drunk, and Tompall tried to out-drunk him. Waylon couldn’t stand Tompall because he was such a drunk.”

Billy Ray’s recollections saunter through two or three hourlong phone calls. And there will be more, as I love his tales of life on Music Row, when the neighborhood characters were folks like Porter and Dolly and Jones and Robbins, the Bradleys, Chet, the Glasers, Bare, Kris, the Rev. Will. Hell, even Elvis.

“Everything has changed from what I knew,” Billy Ray says, suddenly lighting on a night he was wandering the Row with Elvis’ Blue Moon Boys drummer D.J. Fontana. (The two of them often would hang out at the studio owned by Scotty Moore, another dead friend of mine, who just happened to invent rock ‘n’ roll guitar in that early Elvis combo.)

“We went around Studio A at RCA. Next to Studio B. Elvis drove up in a Fleetwood Cadillac. Him and Lamar Fike. He didn’t shake hands. He was just the most awesome sight. I thought he was like a Saudi prince in this suit, with a sash over it. It was real eccentric.” Stunned breathless by the encounter, he listened as the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll and his old drummer swapped memories.

As for the fabled Tally Ho? “I’m not a drinker. I get drunker on a Coke than most people would get out of a jug of alcohol. I was running with Waylon and Johnny Darrell and Faron and George. The Tally Ho was one of the nastiest places in the world. It was a dump. The floor was crumbling. The chairs were broken. We all would be playing our songs,” he says.

“Anywhere they could find a pinball machine, they’d play 24 hours a day. Tompall would be drinking. Waylon would do whatever he did.

“It wasn’t hard to stay occupied. We were all crazy and having a ball. It was a great life, always looking for the next thing.”

That lifestyle, the soul of the old neighborhood, is as far gone as the days when you could hear Tammy Wynette, Jones, hell, even Waylon, on the radio.

“God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change,” Billy Ray says. “The music I knew is gone. The same thing that’s happening on Music Row is happening to the music business.

“We worked hard to make it popular, and darn if that’s not our downfall. They don’t know what country is today.”

Then he laughs. “I gush when I think about how much fun it was. I had a fabulous time.”

Back at what used to be the stomping grounds of Owen Bradley, Harold Bradley and even Bob Dylan, Mike Porter, the Columbia Studio A and Quonset Hut keeper, scheduler, historian and deeply rooted fan, talks more about the Music Row he sees changing every day.

“The music business will always be in Nashville, but will it always be on Music Row?” asks the guy whose career has been spent in audio technology and engineering management.

“The unique part about Music Row being a tight-knit, walk-to-everything community is gone.”

He looks out his window at what is called Music Square East. “I get to see tons of interesting stuff out there, with tourists and the giant guitars. And, of course, I see the pedal taverns, the party barges and the golf carts.

“I can generally tell a Dylan fan by the way they look at the building and point,” he notes, with a laugh. “They look like they are about the age to be old hippies.” My age.

Similarly, he can recognize Patsy Cline fans, who stand by the big guitar statues out front and look toward the Quonset Hut, where most of her great triumphs were recorded.

He views himself as something of an ambassador, and when he sees those people and he has the time, he rescues them from the sidewalk and takes them on mini tours, showing them the sites of those musical milestones.

“Every time I do that, we get another heartbeat, a breath of life in here to hear the story,” he says.

By the way, in addition to standing in Dylan’s spot in Studio A, I followed Mike to the spot where Patsy stood, and he tells me about recent female visitors being moved to tears while standing there.

“I still see people with guitars on their backs, walking up and down the street out there, but mostly they are new in town” and trying to figure out where they should go to find fame. It’s not like the old days when you might see Billy Ray, Waylon, Marty, Cash, Porter or even Dylan out there.

He scans the bit of neighborhood he can see from his office.

“It’s kind of gentrification,” Mike says of what is happening to those old houses when landlords realize how much money they can get for the property, whether by tearing it down or by chasing out the songwriters and renting or selling to It City immigrants.

“What does it do to the rent of those houses?” he asks, rhetorically.

Just as the music format is changing, so is the Row and he expects some sort of “new normal” to settle in eventually.

“Growth and change is necessary,” he says, using the nearby Pancake Pantry in Hillsboro Village as an example. “Used to be, you’d go in there and see Porter, Waylon, choose any star’s name you want. Deals were made there.”

Now those deals happen in corporate offices, and the old flapjacks eatery “is mostly tourists and college students from Belmont and Vanderbilt.”

“The Row is engaging people in other ways,” Mike points out. “The Roy Acuffs and Porter Wagoners are not necessarily there, but we do have a lot of new country acts.”

Perhaps it’s too late to salvage Music Row. That salvation should have come a couple of decades ago.

Of course, a new story is evolving, every time a historic house goes down and a gloriously plush and anonymous condo complex or hotel or business office goes in.

Mike hopes at least he can do his part to keep alive the legend, the myth, the true story of the amazing past along these avenues and studios.

He looks at me. “If we don’t tell the story, who’s going to?”

As Kristofferson told me long ago: “I wish the old stuff was still here.”