VOL. 43 | NO. 9 | Friday, March 1, 2019

Goldrush’s closing simply a sign of the times

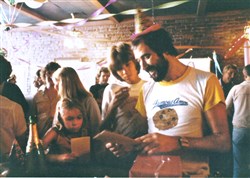

Songwriter Roger Cook (in famous Amos T-shirt) celebrates his 40th birthday at the Goldrush on Elliston Place in 1980. Looking on are his daughter Katie Cook, left, now a host on CMT, and son Jason Cook.

-- Photo Courtesy Of Roger CookThe Goldrush is gone. It may try to reopen in another location, but really, it’s gone. The iconic bar with the swagger and stagger of a drunk biker is now just the font of memories for a generation that doesn’t go there anymore.

Upon the sudden announcement almost two weeks ago, obituaries soon began to flood social media. The string of lamentations mostly came from folks who cut their teeth there 30 to 40 years ago. The Goldrush came of age in the 70s, grew up in the 80s and matured in the 90s.

Then came the decline, slowly at first, but by the time the bar tried to remake its bad-boy image a few years ago it was too late and the changes likely hastened its demise.

The old Gold was swaddled in smoke and sticky with cheap beer. It was simmering calm with a lid on it. Getting rid of smoking got rid of the smokers. Going for the craft cocktail crowd, I think, alienated the base and blurred the lines of distinction of what set the Goldrush apart from the trendy waves lapping at our “It City” shores.

In short, all the grit and grime and rock-block-gangster feel faded away. A few diehards kept the place going, but if the gut-punched fans were truly honest, they hadn’t been there in years and likely had no intention of going if asked to heed a clarion call to save the place.

I remember the sense of danger the first time I went there in 1980. Barely 18, my synapses tingled, fueled by beer and a penchant for neighborhood bars. Fights weren’t unheard of, and an argument in the summer of 1982 left a biker and a Vanderbilt student dead.

Despite that, bartenders and bouncers like Wallace Journey Jr. kept the order. During the murder trial the following summer, when asked whether the biker group was a “tough bunch,” Journey deadpanned, “They’re OK. I don’t have any problem with them.”

With an early happy hour, it was a day-drinker’s delight. In the shank of the night, after rocking on the block at Exit/In or The End, drinkers tilting at the bar ordered infamous bean rolls. They set you straight. Over the years those legumiferous tubes soaked up more alcohol than floating booms grabbing crude oil after the Valdez.

For Katie Cook, CMT host and daughter of legendary English singer songwriter Roger Cook (“I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing” and “Long Cool Woman in a Black Dress”), the Goldrush was where she grew up, literally. She has memories as an 8-year-old celebrating her father’s 40th birthday there and bearing witness to a brawl.

“It felt like the wild west in there at times,” Cook states in a Facebook post. “I remember sitting at the bar as a child nursing my Shirley Temple, when two men got in a fight next to me. One broke a glass over the other’s head. The ambulance arrived and picked glass out of his bloody face right there at the bar.”

I called Cook to ask her what she thinks this means for Nashville, and she sadly admits it’s a harbinger of an era’s end.

“I didn’t help keep it open. I maybe went three times a year,” she says, which is more than most of her contemporaries. “It was from a time when everyone knew everyone. It wasn’t glossy,” she adds, referring to the current high-end condo boom and trendy restaurants.

Cook is philosophical, though, recognizing that change and growth are inevitable.

“There was a time when the Goldrush was new and something else was closing,” she says. “There are new places today that young people will feel that same way about 30 years from now.”

A there’s the simple generational rub. Hipsters are not rending the turned-up cuffs of their $150 jeans. They have their own places while those of a certain age watch old haunts disappear.

The question is, what is Nashville anymore, if not gritty joints that nurtured musicians and songwriters? Yes, change is the inexorable constant, but at such an accelerated pace, we are seeing the fabric of Nashville culture being ripped away and replaced with the glitz not of rhinestones, but of klieg lights and slick outsiders spoiling for a deal.

While there are tax incentives to preserve land, there are no such vehicles to preserve cultural institutions. Real estate drives it all right now, and developers aren’t going to save Brown’s Diner or Fido or Rotiers when the lease is up.

Certainly, it’s a property owner’s right to make good on an investment, and many properties now orbit in the “stupid money” stratosphere. We can only hope for leadership from developers who recognize that certain places add to the fabric of the community in ways that define what brought people to Nashville in the first place.

Admittedly, I’m steeped in nostalgia, mainly because I believe stories resonate more when you hear them in the places where they took place. Others are less sentimental. They value the new over the old. If Roy Acuff had his way, the Ryman would have been long gone.

For the last remaining places in town that are in danger of being swapped for another Walgreens or million-dollar concept restaurant with a chef who flies in from New York once a month, you better start visiting them again if you want them to last. Even then, when the rent gets too high for fried okra to fill the landlord’s coffers, the city will yield to the next new thing.

So goodbye, Goldrush. Goodbye Nashville of a certain age. Juke joints and hip joints eventually need replacing. What Nashville becomes is up to the next generation.

Frost was right. Nothing gold can stay.

Jim Myers is a former restaurant critic, features columnist, hog wrangler, abattoir manager, Tennessee Squire and Kentucky Colonel. Reach him at [email protected]