VOL. 42 | NO. 26 | Friday, June 29, 2018

Dutchman's Curve: 100 years later

By Tom Wood

Standing out here in the freshly-mown grasses of Richland Park Greenway, several yards from the Dutchman’s Curve Train Wreck historical marker placed alongside White Bridge Road, I listen for ethereal echoes of the past.

This is as much a ghost story as it is a history lesson.

Call it ‘Ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve’ because they still whisper to us as the 100th anniversary of the nation’s deadliest train wreck fast approaches. Remember us, they murmur on the gentle wind that stirs the humid air.

It is Saturday, June 9, a little after 7 a.m. – exactly 99 years and 11 months after the accident occurred. Exactly where I am standing on this sun-splashed morning in Belle Meade. One month shy of a day of remembrances that will take place for one of Nashville’s largely forgotten tragedies – yet one that still profoundly resonates with many people nearly a century later.

“From the very beginning of this journey – when I first started this project – I felt like the ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve had chosen me to learn their names and tell their story. I heard their voices and did as they asked,” says Betsy Thorpe, author of the 2014 book, “The Day the Whistles Cried: The Great Cornfield Meet at Dutchman’s Curve.’’

More than a decade ago, Thorpe – who says she quickly became known as the Train Wreck Lady – spearheaded a movement to get the historical marker placed at the site of the wreck. In coming days, she and the NC&StL (Nashville, Chattanooga and St. Louis) Preservation Society will host several commemorative events leading up to July 9, the 100th anniversary of the fateful, life-altering crash.

“The voices of the victims at Dutchman’s Curve still echo 100 years later,” says Nashville Mayor David Briley, who will speak briefly at the greenway memorial observance. “It’s important that we never forget this tragedy in our city or the many people it affected, including the families of the 101 people who died.

“A century after the crash, people across Tennessee still feel the loss.”

On this bright June morning at the greenway, there is indeed an otherworldly feeling, as if time somehow stands still here. Not a presence but a prescience.

Little things – sounds of an airplane rattling the sky moments before the time of the wreck, followed minutes later by a faint police siren that echoes the rescuers rushing to the scene – provide auditory reminders of what it must have been like that mournful day.

“The story of Dutchman’s Curve consumed my life,” Thorpe acknowledges. “Now, 11 years after I first learned of the wreck, the 100th anniversary is near and with it comes closure – not just for me, but also for the ghosts of the hundred men and women who tragically died long ago.”

Why it happened

Nearly one hundred years later, there are still more questions than answers, more speculation than facts about the disastrous chain of events on Tuesday, July 9, 1918, when more than 100 people died in that head-on train collision sometime around 7:20 a.m.

“This was the worst train crash in American history,’’ local historian David Ewing explains. “More people have been killed in fires, plane crashes, floods and other natural disasters, but never more on the rails than on July 9, 1918. It was a sad event for Nashville and this part of the country.

“Because commuter rail service isn’t what it used to be except in the Northeast corridor, Nashville will probably always have the title (of deadliest rail crash) unless an act of terrorism happens on a train,’’ he adds.

Human error played a major role in putting two NC&StL Railway steam locomotives on the single-rail track at the same time.

Basically, the inbound train from Memphis was running late on its way to Union Station. It had right-of-way, and the outbound train from Nashville – running five minutes behind its schedule – was supposed to wait at The Shops (the railway’s roundhouse, repair and track-switching site located near Centennial Park) until the inbound Memphis train passed.

Thorpe covers those theories in her book – from a switch engine allegedly mistaken as the Memphis train to a supposed all-clear signal in the semaphore tower – but ultimate blame fell on 71-year-old David Kennedy, the Nashville locomotive engineer.

View of the baggage car and the first coach of train No. 4, which telescoped on impact. The Nashville crash, and the 101 dead, were quickly knocked off the front pages by World War I news.

-- Photos By Henry Hill, Official Photographer Of The Nashville Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway. Courtesy Of Henry Hill Iii“Kennedy was supposed to wait for the overnight train to go by, but for unknown reasons he didn’t follow his orders,” Thorpe explains. “When I tracked down family members in Texas and Florida, they knew he died in a train crash here but they didn’t know he’d been blamed for it.

“I think David Kennedy had some sort of medical situation (that contributed). I wanted to clear his name, but that wasn’t the case.”

‘A very horrific accident’

Minutes later, the earth shook from the impact of the two trains meeting in the middle of a cornfield. Twenty-eight tons of steel and wood colliding at an estimated 110 mph combined is how Thorpe describes the impact.

Carnage was incredible – bodies burned beyond recognition from the steam of the bursting boilers, many crushed, dismembered and mutilated. Some victims were never identified, and stories are told of Nashville butchers being called to assist doctors because they were used to dealing with … well, slaughters.

“It was a very horrific accident. A lot of Nashvillians don’t know a whole lot about what happened,” Ewing says.

The inch-tall, bold headline in the Nashville Tennessean screamed that 121 people perished in the devastating crash with 57 others injured. The Interstate Commerce Commission’s official report listed deaths as 101, with more than 170 injuries.

“Telescoping” best describes how the two trains were bent, folded, spindled and mutilated. Wooden cars became one, squeezed together like an accordion.

“I was an accident investigator for the Metro police (for 30 years), and I’ve tried to reconstruct the wreck,” says Terry Coats of the Preservation Society. “I looked at the photographs by Mr. (Henry) Hill for years and didn’t realize what I was seeing. The (Jim Crow car) was so torn up that it’s just not there, it’s just not there. The car was completely inside one of the baggage cars.”

Two societal factors also contributed to the large number of deaths, Ewing adds.

View of the baggage car and the first coach of train No. 4, which telescoped on impact. The Nashville crash, and the 101 dead, were quickly knocked off the front pages by World War I news.

-- Nashville Public Library, Special CollectionsThe accident occurred at the height of Jim Crow laws, an era of racial segregation in the South that existed from 1877 to at least the start of 1950s civil rights movements.

The African-American passengers were restricted to crowded, spartan cars upfront that doubled as the smoking car. Meanwhile, Caucasian passengers rode in metal-framed wooden Pullman cars farther back.

Many who died on the overnight train were poor farmers from Memphis and Arkansas en route to Old Hickory to work at a munitions factory.

“The night train from Memphis had more Jim Crow cars. Mostly all of them perished. Most of the white men who died were in the smoking car of the train from Nashville,” Ewing says.

For one day, segregation came to a standstill.

“One of the most startling things for that time (in history) was the color barrier coming down. It happened during the Jim Crow secession era in Nashville, but on that day, they were taking black people to white hospitals and white people to black hospitals. The color barrier came down,” Coats recounts.

The second societal factor was the U.S. was fighting World War I, joining the Allies in 1917 to defeat the Central Powers in November 1918. The federal government had taken over U.S. railways. Train schedules were tightened, crews understaffed and passengers overcrowded.

“By Friday, the news of the dead of the war had replaced the dead of the accident (in newspapers),” Ewing points out. “The death toll was 647 Americans, and 703 died the previous week, so when 101 people died in a train crash in Nashville, it was not as big a story.”

The rumble and the roar

As a sportswriter and rock concert-goer, I’ve heard loud crowds, bands and stadiums. The noise level at those events can be deafening, but is it close to the grinding railcars being crushed like tin cans?

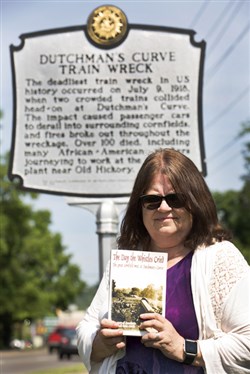

Betsy Thorpe, author of “The Day the Whistles Cried, The Great Cornfield Meet at Dutchman’s Curve’’ (2014), stands in front of the historic marker at the Richland Creek Greenway. Her book can be purchased at Parnassus Books, Belle Meade Plantation gift shop, Wendell Smith’s restaurant, St. Mary’s Bookstore or www.betsyathorpe.com. It is also at the Nashville Public Library or via Amazon, and Thorpe will have copies available at some of next month’s 100th anniversary events.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerComparisons that come to mind are sonic boom shock waves from jets that break the sound barrier, or the massive Fourth of July fireworks show. Maybe thunder booms and lightning crashes, or the 1998 tornado that shredded downtown and East Nashville; people often liken tornadoes to a roaring train.

“It’s a different kind of loud – much louder,” Thorpe says. “Imagine a much quieter world than we live in today. People two miles away heard it. People living off Charlotte Pike thought something had happened at the state prison. It woke people up. People stopped what they were doing and ran toward the sound.”

Both Ewing and Coats say at least 40,000 people rushed to the crash scene to render assistance, or stare.

“As soon as word got out, every private doctor closed his office and took his nurse to the site. Bootleggers brought booze to comfort those who needed a drink. Many came to help, but many came to gawk. It was said that the noise was heard in a two-mile radius of the crash site. That’s a four-mile span. I can’t imagine the horror, the carnage and destruction.”

Neither can Rob Cross, chief historian at Belle Meade Plantation, who calls the train wreck “just a horrendous thing caused by sheer timing. That is so harrowing to think about.”

The plantation, owned by Walter Parmer at the time, sits about two miles from the accident site, and is across the street from where the Harding Station once existed.

Cross says the mansion’s family and workers “no doubt heard the crash” and rushed to help. “This was during World War I. Passengers were soldiers, and Belle Meade Mansion provided agricultural supplies to the government.’’

One family’s story

Onlookers can be seen at far left lining the bridge to gaze at the devastation.

-- Photos By Henry Hill, Official Photographer Of The Nashville Chattanooga & St. Louis Railway. Courtesy Of Henry Hill Iii“Smoking Kills.” My generation grew up with that health warning drummed into heads. But the family of engineer John Nolan has lived that slogan the last 100 years.

Pat Nolan of Prescott, Arizona, lost the grandfather he never knew because John liked to smoke. He was in that upfront segregated smoking car when the two trains collided.

“My grandfather was deadheading to Memphis to pick up his train. He was a smoker and sat in the smoking car behind the coal car,” Pat Nolan recalls. “Normally, he would have been in the caboose with other employees. They all survived, but he was up in the smoking car and didn’t.

“It frustrated my grandmother that he was in the smoking car. It left an absence in all our lives,” adds Nolan, whose cousin (also named Pat) is a Nashville political commentator for WTVF. “I never got to hug him, talk to him or learn from him. It takes a toll.”

Pat says his dad, also named John, was only 8 years old when he lost his father. Family members ran to the ghastly wreck site, and little John saw his father’s body.

“It was quite a shock to find his father’s body, mangled and scorched from the steam. There were bodies everywhere. My dad didn’t talk much about it,” Pat Nolan adds.

“It was too painful for my grandmother. She had a lifetime railroad pass and moved the family to California. I was born in Los Angeles. My dad never went back to Tennessee. His mom did. Obviously, it was painful for everybody in the family.”

Nolan first visited the wreck site in 1968 with his father’s cousin and will be in Nashville next month for the 100th anniversary to honor the ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve.

“It leaves a hole,” Nolan explains. “(My grandfather) was somebody who loved railroading. To have that accident, those telescoping cars, to think of all the things that might have been. It left a crease in everybody’s heart.”

Immediate aftermath

Because of the way accidents today are investigated and how the media reacts, a similar incident would be at the top of the news cycle for months. The 2010 Nashville flood coverage is one example.

But that wasn’t the case 100 years ago.

“It was front-page news for two days, then the news of World War I replaced it on the front page. That was the kind of thing most everyone was following at the time,” Ewing points out.

“That (investigation) was one of the most unusual things. If a plane crashed today, the NTSB would go out to the site where the plane or train crashed and spend weeks and weeks investigating, talking to people and looking into all the facts of what happened before even thinking about filing a report. That’s not what happened here.”

And the government’s role has been questioned by some who suggest engineer Kennedy was made a scapegoat.

A few years ago, songwriters Joel (The Singing Cabby) Keller and Marci Salyer Nimick penned “Dutchman’s Curve.” Keller now lives in Nebraska but will be back in Nashville singing at one of next month’s commemorative events. One line from their song asks, “Did the government suppress (evidence)?”

It’s a valid question for a hurried probe and desire to get back to work. Crews worked feverishly to clear the tracks and get back on schedule.

“It was not investigated thoroughly. The only people interviewed were employees of the NC&StL, and if you were an employee, you were going to have the company line. Passengers were not questioned,” Ewing says. “The Interstate Commerce Commission’s official report was filed within a matter of weeks and was only six pages long. The crash occurred at 7:20 a.m., and by 7 p.m., the track had been cleared and the trains were running again. Literally by that evening, everything had been moved aside, and it was business as usual.”

Adds Coats: “(The cars) were all wooden construction. The only metal cars were the Pullman cars on the back. The ICC official report suggested that not half as many deaths would have occurred if they had all been metal cars. The NC&StL was not a rich company, and it could not meet the ICC recommendation that they switch to all-steel cars.”

Lost in history?

On my June stroll along the greenway, I asked a handful of people if they knew the history of Dutchman’s Curve. Only one had.

“I’ve read the marker, it’s a quite fascinating story. It was a sad day, really strange how it happened,” says Ed Copier, 91, who has only lived in Nashville six years. “It seems like they got their signals mixed.”

Experts are split on whether it’s a lost story in Nashville history.

“I don’t think so,” Thorpe says. “To people who live in West Nashville, to people who have family who died in the wreck, they have never forgotten what happened here. When you talk to those relatives, they all remember it and have family stories to share.”

Coats and Ewing disagree.

“I’d say 90 percent of Nashvillians have no idea of what happened at Dutchman’s Curve a century ago,” Coats notes. “This month’s events will generate a little enthusiasm, so it will get back in the minds of a few people. But any lessons have been long forgotten.”

Ewing says the 100th anniversary tribute to the ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve will raise awareness.

“A lot of Nashvillians don’t really know a lot about what happened. It got lost (in history) pretty immediately,” Ewing continues. “It wasn’t treated the way milestone events are today. A year later, there was nothing (in the papers). There were no two-year, five-year, or 10-year anniversaries of the wreck. It’s a sad thing.”

But it would be unfair to say Nashvillians have totally forgotten the ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve over the last century.

Articles have appeared in various publications through the years, WNPR aired a “Curious Nashville” podcast for the 99th anniversary last summer, and Nashvillians Chris Lambos and Kirby Allen have produced a short video, “Dutchman’s Curve, America’s Worst Train Wreck,’’ which will be shown at next month’s anniversary dinner.

Lambos says it will “touch on a few intimate recollections of how some families were affected by the tragedy – in some interviews, the emotions stirred by this 100-year-old tragedy can emulate the pain from a fresh wound.”

Singer David Allan Coe’s sorrowful “The Great Nashville Railroad Disaster” was released in 1980. The lyrics, written by Bobby Braddock and Rafe Vanhoy, concludes with:

“Now every July 9th a few miles west of town

"To this day some folks say

"You can hear that mournful sound.”

Barring unforeseen circumstances, I’ll be at the greenway at 7 a.m., on July 9 for the 100th anniversary observance.

I don’t know what the weather will be like, but a little drizzle – tears from heaven – would be appropriate, to feel the spirit of the ghosts of Dutchman’s Curve.

“After the events of the anniversary weekend are over I hope that they are satisfied and that their story has finally been told,” Thorpe says. “To them I would say, ‘Sleep well my friends. May you all rest in peace.’”

I have a feeling they will. We remember.