VOL. 42 | NO. 11 | Friday, March 16, 2018

Secours looks to stars in praise of scouts who discovered them

Filmmaker Molly Secours with Hall of Famer George Brett, left, and veteran Kansas City Royls scout Art Stewart.

-- SubmittedWillie Mays – or at least recounting the day she met and filmed the man some say is the greatest baseball player ever – makes Molly Secours light up.

Actually, almost anything about baseball makes her happy.

“I watched 90 Cubs games last year,” she says, talking about her immersion into the game, thanks to her film “Scouting for Diamonds” about the lives of baseball scouts and the sluggers and glovers they escorted to fame.

Molly was passive about baseball until she started making this feature-length documentary about scouts.

But on this afternoon, as she talks about the heart of her film – the proud sub-culture of baseball scouts – Molly illustrates how she’s been smitten by the game by recounting her meeting with Willie.

Molly Secours interviews Willie Mays at AT&T Park in San Francisco.

-- Submitted‘The Say Hey Kid” defined the word “superstar” simply by the way he lived … the way he hit the ball … the way he caught the ball ... the way he changed even how players wear their gloves … the way he loved the game in general.

“It had a kind of sacramental nature about it,” Molly adds, describing the encounter she and her cohorts in this film venture had with Willie.

“His presence is amazing, even in his 80s and in diminishing health,” says this woman who regularly seeks the wisdom of her elders, some quite famous, while connecting the dots of a pretty magnificent life.

Her life and her film make up the bulk of our conversation on a crisp March afternoon in Nashville.

But the day she met Willie, to learn about his scout, the late Ed Montague Sr. – who signed him for the old New York Giants baseball club – dominates the conversation. (Willie, like the ballclub that began as the New York Gothams, fled the Polo Grounds in 1958 to play in San Francisco’s minor league Seals Stadium in the Mission District while waiting for Candlestick Park to be built.)

“He has the most self-confidence of anyone I’ve met,” she explains. “When he speaks about his talent, he’s not bragging.” He was speaking the unvarnished and proud truth.

“It was really amazing to be around a person like that.”

She admits to a certain level of jitters when she interviewed Willie in his suite at San Francisco’s AT&T Park.

If you don’t know anything else about that stadium, you likely have seen footage of people in kayaks navigating cold San Francisco Bay waters beyond right field, trying to rescue balls that have cleared wall and splashed down in what’s unofficially called “McCovey Cove,” for Giants’ great first baseman Willie McCovey.

The cove was a particularly popular piece of B-roll TV footage back when a well-juiced Barry Bonds conquered the single-season and lifetime home run records.

In a fair and just world, the home run marks still belong to Roger Maris who in 1961 broke Babe Ruth’s single-season record with 61 homers (without steroids), and Hammerin’ Hank Aaron’s lifetime tally of 755 (again without steroids). Bonds retired with 73 homers in a single season and a lifetime mark of 762.

Anyway, back to Willie and Molly in the exchange filmed for her movie about baseball scouts, a project that has consumed her for four years and which she plans to finish this summer.

Former umpire Ed Montague Jr. (who now works as a scout to find umpires) had facilitated the conversation and was with Molly and her crew.

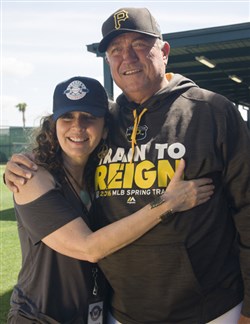

Molly Secours and Pittsburgh Pirates manager Clint Hurdle

-- Submitted“I was nervous, of course. I knew how direct (Willie) was. He wasn’t warm and fuzzy with everybody.” She laughs.

Montague began the conversation, but then Mays turned his attention to the dark-haired social activist, author and speaker (“I guess you can call me a filmmaker now since that’s all I’ve done for four years,” she says to me).

“Three minutes into the interview, (Willie) tapped Ed on the shoulder and said ‘I want to hear it from her. What you got to say, baby?’

“I really think it’s the most in-awe I’ve ever been,” Molly acknowledges. “His sense of presence was so striking. And his exit from the suite when the interview had concluded rattled the emotions of everyone who watched him leave.

“When he left – he had got out of bed and was in his slippers when he came to see us – he left us in his suite.

“When he walked out the door all of us (including cinematographers Ben Pearson and Dave Ogle) started crying,” she recalls. “We all knew we’d been in the presence of greatness.”

As noted earlier, her film is not about the stars like Willie and Wade Boggs – another who surprised her with the depth of emotion and affection he so freely displays when talking to the camera about his scout.

“Scouting for Diamonds” uses those players’ recollections to paint a proud portrait of the men who had gone out to dusty fields of dreams, taking notes on prospects.

Current stars like former Vandy ace David Price, the Murfreesboro native who has used his magnificent arm to broker millions from various teams, the Pirates’ Clint Hurdle, Cubs’ Ben Zobrist, Pablo Sandoval (when he was with the Red Sox) and Orioles catcher Caleb Joseph (who played college ball at Lipscomb), Royals immortal George Brett and so many more contributed remarks about the scouts who found them.

The front office is represented by folks like Red Sox president Dave Dombrowski.

Even Vanderbilt baseball coach Tim Corbin is asked for his take on the men Molly focuses on in her movie: The guys who hang onto the fence at Hawkins Field to figure out which Commodores and opposing players are ready to finally cash in on their kindergarten goals of glory.

So far, Molly and her crew have interviewed 151 people. And they are ready to collect more interviews out in Arizona, where they’re watching 2018 spring training.

“This is our third spring training,” she adds, noting that they catch a few games, watch the ballplayers and, if lucky, capture interviews with the film’s heroes, the scouts and the players who love them.

She says one reason she likes spring training is the horde of athletes, coaches, managers and scouts in one small slice of Earth.

“It’s sort of an economizing the funds for the film. You go there and everybody is there.”

There also is “a lightness at spring training,” she explains. The season is a few weeks off, and the players and coaches have yet to lose their virginal World Series championship dreams. Every team is undefeated until the end of Opening Day.

With the spring training crack of wooden bats meeting balls as an optimistic soundscape for those dreams, the men interviewed are less guarded.

“I’m telling you, they’re all like an 8-year-old child when they’re at spring training,” Molly says.

Buoyed by similar championship hopes for her film, Molly is scouting out help to clear the left-field wall of her dream project.

“We still need $200,000,’’ to finish the movie, she says. A few philanthropists and others have invested, but 2018 is the season Molly swings for the fences in the fund-raising game.

“I could’ve gone after Hollywood money, but I didn’t want that. This isn’t a Hollywood movie.”

She knows all about Hollywood money and movies because she at one time was knocking on doors there, attempting to launch an acting career.

The height of her celluloid fame came with a featured role in a movie called “Baby Fever.” She urges this writer not to judge her by that particular film role and encourages people not to seek it out on some obscure TV channel’s late-night offerings. This film about career-women facing the biological clock is also available for streaming. I may give it a shot, as I’m sure Molly’s brilliance will shine through.

“I was out there from 1989 to ’93. Yes, I was doing pretty much acting and a lot of waiting on tables,” Molly recalls of her Hollywood days and nights.

The meat-on-the-hoof nature of chasing film success ultimately led to her relinquishing those dreams. “You don’t just act. You have to be hired. You spend so much time begging people to pick you (for their film).”

With her love affair with Tinseltown turned sour, she sought success elsewhere, in a fistful of different fields.

“I’ve had experiences in my life, without sounding strange, I’ve always had the feeling of being guided. I have adhered to that guidance.

“I remember waking up one night when I was living in California. I decided I didn’t want to live my life waiting to be chosen. That whole idea of putting on a costume to try to entice somebody to hire you, it never felt like home.”

She also succeeded in corporate public relations for awhile. But that wasn’t her thing either. “I didn’t want to mix my acting career with a P.R. career,” she adds, with a bright laugh.

Her wanderlust was fueled when she fell in love with a musician, Steve Conn, an accomplished keyboard man (and so much more) who has toured or recorded with Bonnie Raitt, Albert King, Kenny Loggins, etc.

“He’s the most amazing musician I’ve ever met,” she says of Conn.

Unencumbered by grownup requisites and very free spirited, she followed Conn to Music City.

“That’s how I got here (to Nashville),” she explains. “I thought we were only going to be here for three years. I’d never lived anyplace longer than three years. I never thought I would like life in the South.”

For some reason the forces that guide her brought her to the right spot.

“I just ended up falling in love with Nashville and was drawn into things I never anticipated.

“I came here from L.A. and before that I lived in Denver. But I got here and was so charmed by it. By things like the postal worker who gives out Christmas cookies his wife baked.”

That sort of charm hooked her, so even after she divorced the acclaimed musician – “we remain great friends” – she stayed here. It was home. She became a Nashvillian.

“I remember moving here, and Nashville was so charming and endearing and interesting.”

She acquired friends here: Folks like John Jay Hooker, John Seigenthaler, the Rev. Will Campbell and so many other legendary figures of Nashville society, culture, faith and philosophy who welcomed her to their circles.

Those wise men now are all gone, and Molly wonders “where’s the next generation of leaders?” Course, she could just look in a mirror.

She laments the charm that drew her here “is kind of going away. Too many people moving here from other places. … When I moved here, there were like three restaurants. Now I can’t keep track of all the openings and closings.”

“I haven’t had an imagination for any other place, though. I travel a lot, but I miss the saltiness and soulfulness of the South when I am at other places.”

A proud survivor of Stage IV uterine cancer, she has embraced a number of causes in her speeches and her many writings. She is an old-fashioned, passionate activist, tilting at society’s most-lopsided windmills.

But, as she told me earlier, right now she is a filmmaker. After producing a series of 15-minute biographical documentaries, she knew she wanted to make a full-length film.

“I started with a little video series called ‘Lasting Legacies,” she points out.

It was pretty much fate or supreme guidance that led her to begin “Scouting for Diamonds.”

It started out that she was going out to Gallatin to meet legendary Red Sox scout George Digby, the man who had signed Wade Boggs and had sought to sign Willie before the Red Sox decided it wasn’t time to break the Green Monster of a color barrier. That little trip was sparked by a conversation with a couple of Little League coaches she encountered.

“They didn’t know anything about film. They were friends with a scout named George Digby. He was 96, getting on in years and not doing well. I thought it would end up being a 15-minute video (about him).

“That was on a Thursday. I was going to go out and meet him, but he died the next weekend.”

That actually fueled her to realize that what she wanted to do was different, she desired “a love story” about the scouts and the men they’ve given careers and the voices of the living.

While she never met Ol’ George, “he’s been whispering in my ear ever since. “

When Molly describes the film to her friends, “to this day, they don’t understand. Baseball is a backdrop. This is about the people.”

Her own love of the game began when she met and interviewed this sub-culture of men, becoming almost (not quite) an insider. As noted earlier, her love of America’s pastime is demonstrated by the 90 Cubs games she watched last season.

She says the narrator of her film, actor and unrepentant Cubs and Harry Caray fancier Bill Murray, “may have had something to do with it.”

“I also like the Royals and the Red Sox.’’

I am anxious to see her film, after watching the trailers. It reminds me of my old days as a sports writer 40 years ago and jawing with the scouts, the guys with clipboards and stop-watches, sitting in the high school and college grandstands, looking for the next Willie Mays.

They’d sit with others of their profession, almost to a man chewing tobacco and spitting tidy brown streams into the dust outside the foul lines.

It may be set in baseball, but this truly is a Great American tale using baseball as sort of a microcosm of what is good about life in the land of the free, home of the brave.

I probably shouldn’t end this by saying Molly is consumed by this film. It does take up her days. But then there are the days she spends walking her King Charles Cavalier dog in nearby Shelby Park.

“Simone is everything to me,” she says. “She does everything with me. She even kayaks with me. She’s a water dog.”

Molly and Simone often seek out quiet, clean places to kayak. But most often, their kayak goes into the river near her East Nashville house.

“In the summertime, well, I live right off Shelby Park; I get a lot of flak about kayaking in the Cumberland. …

“But I just bless myself before I get in,” she continues. “Sure, it’s bothersome that it’s dirty. But I just get in the kayak, and it’s nothing but me and the sky.” And Simone, the water dog, of course.

Her waterborne daydreams no doubt include memories of the day she met The Say Hey Kid.