VOL. 41 | NO. 40 | Friday, October 6, 2017

Striking the right balance between science, religion

By Hollie Deese

Louis Kuykendall has been teaching chemistry at Goodpasture Christian School for only eight weeks, although he is a familiar face around campus.

A football coach at the school for the past 13 years, he transitioned to teaching science this school year after retiring from the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation as a forensic toxicologist and field agent.

It’s his longtime background in science that helps him teach students the practice of gathering and applying scientific data. It’s his belief in God that enables him to help students explore and question science further as it applies to their faith.

The two are not mutually exclusive in his classroom.

“I spent a long time as a scientist out in the world, and I think one of the misconceptions is that all scientists are atheists or all scientists don’t believe in God,” he says, adding nearly 80 percent of the group of nearly 100 forensic scientists he worked with were people of some faith.

“I would say the majority of them had a creation view of our world, even though they were highly acclaimed scientists and understood that there’s another paradigm to look at.”

Kuykendall says that issue doesn’t come up in chemistry in the same manner it might in biology because he isn’t specifically teaching evolution. Rather, he focuses on teaching the scientific method, observing data, experimenting with data and theorizing on data. And most people can agree, no matter your religion, numbers don’t lie.

“The funny thing is whether you are a creationist or whether you are a Big Bang theorist, when you look at chemistry and physics, pretty much everybody agrees on the data,” Kuykendall points out.

“What they don’t agree on is interpretation of the data. So, we study the data, and I talk about their interpretation, I talk about my interpretation, and I give those reasons for why both of those exist.”

And being able to approach science from the perspective of a believer makes for a more well-rounded student, Kuykendall says.

“We think a broader view really drives home what I’m trying to teach as the scientific method,” he adds. “I’m not in there teaching ‘Christianity’ or teaching creationism. I’m teaching how a scientist approaches data, how a scientist looks at data.

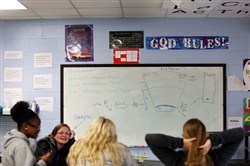

Science teacher Louis Kuykendall talks to students during a lab experiment.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“And what lens they look through does determine some of those analytical outcomes. We’re really just trying to teach critical thinking.”

History of religion in Tennessee schools

Tennessee has long been a hotbed of activity when it comes to teaching creationism in any classroom, including public schools.

In 1925, the Butler Act was signed into law by then-governor Austin Peay, which made it a misdemeanor punishable by fine “for [a] teacher in any of the Universities, Normals and all other public schools of the State which are supported in whole or in part by the public school funds of the State, to teach any theory that denies the Story of the Divine Creation of man as taught in the Bible, and to teach instead that man has descended from a lower order of animals.”

What followed that same year was one of the most famous trials in the country’s history when Dayton high school science teacher John Thomas Scopes was accused of teaching evolution. He enlisted the aid of the American Civil Liberties Union to organize his defense. His trial began July 10, 1925.

Accounts have it that streets were filled with spectators for the “Monkey Trial,” including preachers with tents and vendors selling everything from toy monkeys to Bibles. A chimp in a suit could even be found.

Inside the courtroom, each day’s proceedings began with prayer at the insistence of the judge, who also ruled expert scientific testimony on evolution was inadmissible on the grounds that it was Scopes who was on trial, not the law he broke.

Scopes’ lawyer Clarence Darrow switched tactics and called prosecutor William Jennings Bryan to the stand in an effort to discredit his literal interpretation of the Bible.

It worked, and in his closing statements, Darrow even asked the jury to deliver a guilty verdict so they could appeal. This denied Bryan his opportunity to deliver his own closing statements.

The jury complied and, after eight minutes, handed down a guilty verdict, with the minimum fine of $100.

In 1927, the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned Scope’s verdict on a technicality, but the Butler Act still wasn’t repealed until 1967.

Posters like “God Rules” and other spiritual phrases line the walls of Louis Kuykendall’s science class at Goodpasture Christian School.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerIn 1968, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the First Amendment’s Establishment Clause not only prohibited laws that established a state religion but also prohibited laws that furthered any one religion over others.

Then in April 2012, the controversial Tennessee bill HB 368/SB 893 passed, which protects “teachers who explore the ‘scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses’ of evolution and climate change.”

The bill also contends “the teaching of some scientific subjects, including, but not limited to, biological evolution, the chemical origins of life, global warming, and human cloning, can cause controversy” and that teachers “find effective ways to present the science curriculum as it addresses scientific controversies. Toward this end, teachers shall be permitted to help students understand, analyze, critique, and review in an objective manner the scientific strengths and scientific weaknesses of existing scientific theories covered in the course being taught.”

Teachers feel free to talk

Daniel Jenkins teaches 9th grade biology and 11th and 12th grade environmental science at Goodpasture. At the school for six years, he previously taught at Cheatham Central High School for 19 years.

He says teaching science at a Christian school is different from teaching in a public school because he can approach it from a biblical standpoint.

“At a public school you have to be careful about your curriculum and sticking with what’s in the book and what the state allows you to teach,” he recounts.

“At Goodpasture, we can reach out to the kids and help them to become more involved as a Christian and more involved in the process of creation and how that affects their personal lives.”

That doesn’t mean students’ questions are very different in public or private schools, but how Jenkins and other teachers can handle them is much different.

“At Goodpasture, we can get into the Scripture, and we can delve into those problems by using the word of God. At public schools, not so much,” he explains.

Louis Kuykendall interacts with students during a science lab experiment.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerGoodpasture president Ricky Perry is the one who ends up fielding any calls from parents if there is any conflict over something from class, but that is rarely an issue.

“The majority of our parents are believers, so they approach life through the lens of the eyes of a believer,” he acknowledges. “If you’re going to expose kids to all truth, and we believe that the Bible has been offered by God, I really feel like some of our public school friends are cheated because they can’t consider that as the truth, truly as God’s writing to us.

“So, I really believe that we give the kids more of an opportunity to know all the truths that are out there, and then make their own decision.”

Perry says parents who send their children to Goodpasture are very much looking for an integration of faith in all aspects of the education of their children.

“The lens that the vast majority look through is the lens that God created this world, and he sent his son Jesus to show us how to live and how to have life,” Perry says. “So, they want that in science, they want it in math.”

Excellence in science a priority

Jenkins is the parent of a current Goodpasture high school student, as well as a graduate who is currently a student at the University of Tennessee. Academic excellence is as important to him as approaching those academics from a biblical point of view.

“Our goal, as students come into the high school, is to get them to start thinking critically, instead of memorizing and regurgitating, to solve problems,” Jenkins explains.

“And in doing that, this allows them to be able to learn how to study, how to take tests, and how to be successful in college.”

Kuykendall’s wife is also an instructor at Goodpasture.

She taught in a public school for 18 years in a different state, but as the couple saw their kids hitting middle school they wanted more opportunities for them than their small town with just a few sports and limited extracurricular activities could offer.

The spiritual boost they got at Goodpasture was just icing on the cake to the new rigorous academics their children got in the move.

“They were good students where they were,” Kuykendall says. “When they got here, they really had to shift gears. It was a very positive thing. The spiritual aspect at Goodpasture wasn’t in the forefront of my mind, it was more of an excellence factor.”

Kuykendall knows when his students are in class they are going to learn the best, calculating values, interpreting data and taking the first steps toward being a forensic scientist. It’s the spiritual atmosphere in the school community where he really sees a benefit.

“Where my kids experienced a religious or a spiritual side was really more in the personal relationships that they developed with these different teachers and coaches, because that’s where Christianity meets the road,” Kuykendall adds.

“I can teach non-evolution all day long, and I can teach the theory of the Big Bang theory all day long. That’s not going to create a better spiritual person.”

Perry says students participate and excel in science fairs, from environmental to robotics, and embrace the STEM approach to teaching that pushes technology, science, engineering and mathematics.

And for others to think you need to settle on academics in exchange for spiritual guidance at a Christian school are mistaken.

“God wants our very best, and he deserves our very best, and I think that excellence that Louie talked about, that’s attractive to parents, it’s attractive to kids,” Perry says.

“Sometimes they don’t realize how much they have to invest to be excellent, but usually when they’re looking back, maybe not even in the moment, they really appreciate the fact that they were pushed, they were encouraged, they were demanded to be excellent, and I think that is something that’s a little different way to look at it.”

Science, religion has long relationship

Science and religion have always had a strong relationship says Sister Anne Catherine, principal at St. Cecilia Academy in Nashville, who points out the creator of the Big Bang theory was Catholic, among other prolific scientists.

“Faith is not at odds with science,” Sister Anne adds. “It very much goes hand in glove with science. But faith goes beyond science.

“Science is wonderful in helping us answer questions about the creative world, and then faith points to well, who is the author of that creation?”

In Catholicism, she says, people believe the order within the universe and laws of motion, the world in which we live, operates according to a very logical, orderly, beautiful law with an intelligent creator as the source of it all.

“In a Catholic school, teaching evolution would not be at odds with what we would do, but yeah, there’s a Creator,” she points out. “So, at some point the creation of the human person with a rational mind and a soul was given to him by God. He’s a unique creature, man or woman, and at some point God infused that soul.”

She points to the recent eclipse as the perfect combination of science and belief in a higher power.

“You look at that stuff and you think, ‘Whoa, there’s something bigger behind all that,’” she says.

“We could project it down to the millisecond when the moon would pass over.

“But I think in something like that, you see your smallness. And rather than be despairing or discouraged about that, it kind of makes you think there’s something bigger, but there’s a purpose and an order here. Who didn’t feel wonder and awe when they saw that?”

Because the Catholic viewpoint is one that believes faith and reason go hand-in-hand leading them to God, the scientific method can help answer certain questions about the creative world, about the things we can see and measure and touch and hear.

“God gave us a mind to know, so we want to use it,” Sister Anne says.

“We want to use it to discover all the beauty and order in this world that He’s given us. That’s how we approach it,” she adds.