VOL. 41 | NO. 38 | Friday, September 22, 2017

Metro cops grapple with growth

By Linda Bryant

In Nashville, easily one of the fastest-growing and most-talked-about cities in the country, how do we know if our police officers are getting the job done in our neighborhoods and on our increasingly congested streets and highways? Are they keeping up with the growth?

And how do we determine if the police are – or aren’t – making life better for us as residents?

Zoom in on the Metropolitan Nashville Police Department and you’ll find a force of 1,403 officers working to protect a city of about 685,000.

The makeup of the force is about 80 percent white and 84 percent male, but the department says it is determinedly trying to change that fact by rigorously recruiting minorities and women. The latest census data from 2010 showed the racial makeup of Nashville as 61 percent white, 27 percent black and 12 percent other minorities.

MNPC is attempting to address the growth with mixed results.

There’s room – and funding – for more than 100 new officers, and Metro government is in the process of negotiating the acquisition of the former Kmart store at 2491 Antioch Pike for a new police precinct, the city’s ninth.

Legislation proposed by Mayor Megan Barry and passed by the Metro Council this summer will provide funding for purchasing and replacing in-car computers with enhanced technology to mesh with the department’s upcoming dash cam/body camera program.

But like any big city, the Metro Police Department is dealing with serious issues such as the opioid epidemic and the persistence of gangs, issues that stretch time and resources. Meanwhile, Nashville’s neighborhoods grapple with feeling safe and secure and addressing pesky neighborhood issues such as vandalism and petty theft.

It prompts many questions:

-- How does the department prioritize its resources?

-- Are our officers responsive, friendly and capable?

-- When you do call for help with a problem, what makes an officer respond – or not?

-- Could a situation happen here such as the troubling riots in Ferguson, Missouri, in 2015?

‘You have to call’

Officer Monica Blake laughs after dancing with Ernesto Rivera during the El Protector Program at The Global Mall in Antioch.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerIt depends on who you talk to, but some residents insist that police response to neighborhoods’ concerns can be good, even excellent. Others, even those who say they thoroughly support the efforts of MNPD, admit they get frustrated because they have to wait too long for an officer to respond to their concerns.

Pete Horton, a resident of the Woodland-in-Waverly historic district, says his neighborhood started to get a good response from the police after they began inviting representatives from their Midtown Hills Precinct to neighborhood meetings and events.

“The better you can stay in touch with the police, the better they are,” Horton says. “You have to make it a priority to look up and down your street and know what’s going on. Know that when the kids are out of school, they are more likely to get in trouble.”

Woodland-in-Waverly is a gentrifying, racially diverse neighborhood of about 354 residents near the 8th Avenue South and Wedgewood Avenue intersection and Interstate 65.

Getting neighbors to organize as a cohesive group, Horton adds, and stay diligent about watching their streets and alleys can be a tall order in a time when people are moving in and out of Nashville neighborhoods quickly and when many households are made of families where all the adult members are working, commuting and, well, distracted.

But getting organized and aware is essential for success, he insists.

“You have to call [the police] and call consistently,” Horton points out. “A lot of people look the other way, especially when it comes to petty crime, but it’s best to report every single incident. They [the police] put a pin on the map where the incidents happen and they make the areas with pins a priority.

“I’ve felt like they welcome people getting involved, and when you’re really experiencing crime problems, they will come out and help get things organized. People should realize most of Nashville police really want to help. I haven’t experienced anything different than that.”

Horton says his neighborhood worked for several years to establish a good rapport with the Midtown Hills Police Precinct at 1441 12th Avenue S., and now they respond, usually promptly, to concerns from the minor to the major.

Recently, Horton’s wife noticed someone trying to remove a piece of sculpture from a neighbor’s yard, she called the police and they came. It turned out the incident didn’t involve a robbery; the resident had asked for the yard art to be removed.

“The point is they respond, they come to our homes and meetings,” Horton adds. “The reservoir of goodwill carries over and benefits our neighborhood.”

Salemtown: A mixed bag

Lindsey Marie Cox, president of the Salemtown Neighborhood Association and resident of the neighborhood for six years, says she’s “grateful and supportive” of MNPD but “at times frustrated.”

“We don’t have as much hard crime here as we used to, and we laid a lot of groundwork for that to happen when Salemtown was in the Central District Precinct along with downtown Nashville and four other neighborhoods close to the (State) Capital,” Cox points out.

“We were switched to the North Precinct, and it is a much larger district that covers 112 square miles. [North Precinct] is an area where there’s serious crime that can include things like stabbing and shootings. When you call about a property crime, it usually doesn’t have the same priority it used to.

“I’m not saying the police blow us off – they never do that – but if you call at midnight on a Friday night, chances are you aren’t going to see them until the next day,” Cox acknowledges.

Salemtown has about 750 households, and most crimes “have moved into the category of property crimes like stolen lawn mowers, patio furniture, and car break-ins,” Cox says.

“I do understand that a shooting is going to take priority [over small property crimes]. But our user experience is different now, and it can be frustrating when it takes several hours for an officer to show up.”

Cox has a positive critique as well. She praises the North Precinct for “increasing engagement touches in the neighborhood by at least three times.” By engagement, she means that officers are much more likely to come to neighborhood meetings or events and make visits through the neighborhood that involve communicating with residents when no crime is being committed.

“There is still a tension’

It’s no secret in Nashville that some residents in the city’s less affluent – and primarily minority neighborhoods – often don’t trust the police enough to build strong relationships, and the results are predictable.

Kennetha Patterson, who says she has lived in Hermitage and the Edgehill neighborhood, explains her experiences with MNPD have often been problematic, although she notes that she’s had positive experiences.

“You always remember when they distribute toys at Christmas, and I did see them handing out groceries at a block party yesterday.

“There’s just not enough trust at this time, and in some neighborhoods police still have a negative connotation that works against them,” Patterson acknowledges.

“People end up being scared to call the police for just about anything. I don’t think everyone has this experience, but some people in black neighborhoods really do end up saying to themselves, ‘If I call the police they might not help me, I’m going to get in trouble.’”

Patterson adds she called the police about a critical incident involving a dispute between two drivers (she was a passenger) two years ago, in which she felt “marginalized.”

“I ended up feeling like my concerns weren’t addressed or even listened to,” she says. “I’d venture to say that there are people here who don’t feel like the police are on their side. There’s still a tension between the community and the police in some places in Nashville.

“I just don’t know how you can get people in some of these neighborhoods to call the police when they have something important to report if they are scared, to begin with.”

Though Woodland-in-Waverly is within walking distance to Edgehill, and both areas are diverse and going through gentrification, Edgehill has many more residents – more than 5,000 – and has a higher poverty and crime rate than Woodland-in-Waverly.

The crime difference between the two districts is notable.

Statistics compiled by Trulia for home buyers and sellers show four arrests, 13 counts of assault, six counts of vandalism, 13 counts of theft and two counts of burglary in Woodland-in-Waverly this year.

Edgehill, by comparison, had 199 counts of theft, 194 counts of assault, 160 arrests, 66 counts of vandalism and 55 counts of burglary.

“Anything they [the police] can do that makes them seem less intimidating is great for neighborhoods,” Patterson adds.

“I just think this is a mistrust that gets passed down the line year after year. The more the experience changes, the more real lasting change can happen in our neighborhoods.

“So many little kids want to grow up and be an officer, but in the neighborhoods I’ve lived in something happens along the way to make them change their mind.”

Patterson also is concerned about gentrification affects in Nashville, particularly in Edgehill, where she questions whether the upscale 12South neighborhood is taking resources away from more modest neighborhoods such as Edgehill.

“It seems like I see the police ride around a lot, but I’ve seen more in 12South than Edgehill,” she points out. “Sometimes it feels like they are trying to keep the outside people out of that neighborhood when the focus needs to be on the safety of all the neighborhoods, especially where the kids are.”

Gaining trust over time

Sargent Michelle Jones with MNPD.

-- Michelle Morrow | The LedgerSgt. Michelle Jones, community coordinator of the Metro Nashville Police Department for the Midtown Hills Police Precinct, located in the center of the Edgehill neighborhood described MNPD’s system of prioritizing calls.

“Code 3 is our highest, that means lights and sirens,” she says. “Code 2 is an event such as a car stranded on the road or a car crash. We also make those a priority, especially during rush hour traffic. Code 1 is for our report calls. Each precinct has a security booth that is staffed with an officer that takes report calls.”

While Code 2 and 3 are the most important in terms of response time, it’s not uncommon for there to be a quick response to Code 1 calls, but it all depends on the availability of officers at any given time. But there’s no doubt that if you’re in a car wreck or the victim of a felony crime, you are at the front of the line.

Jones, one of 20 female African-American officers at MNPD, acknowledges her precinct is working to gain the trust of residents and is aware of mistrust issues in some neighborhoods.

“We are very big on community engagement at the department,” Jones says. “When I go into the community I say, ‘Don’t look us at us as police officers look at us as your neighbors.

“This is especially true for the zone officers because they know what’s going on in their areas,” Jones adds. “People, especially kids, see them around, and they are able to build a relationship. [It’s very important to connect with neighborhood kids] “before they are teenagers so they feel comfortable going to an officer and talking to them.

“We want to bring the neighborhood together so that we can build the neighborhood up and do something great.’’

Jones says there have been significant improvements in the Midtown Hills precinct neighborhoods, including Edgehill since it moved to its new headquarters from Antioch three years ago.

“We know a lot of the kids are raised not to like the police so we are trying to bridge the gap and let them know that the police are here to help,” Jones says. “We are out in the area connecting a lot more, and working to find ways for kids to have more activities so they aren’t getting in trouble as much.”

Jones also acknowledges the disparity between the racial makeup of the police department and Nashville’s population as a whole.

Sargent Michelle Jones, left, and Officer Monica Blake react to a little princess who stopped to show off her dress.

-- Michelle Morrow | The Ledger“We want more of the African-American community and people of various backgrounds and colors to work with the force,” she offers. “Our recruiter goes to places like Fisk University and TSU that are historically black colleges. We just had a Citizens Police Academy for young men that was phenomenal.”

What would Jones change about the current MNPD?

“If I could wave a magic wand, it would be to get more officers on the street,” she says. “As far as recruiting, it’s not that we’re not trying. But as far as culture and society are concerned, we were raised not to talk to the police.

“That’s why (minorities) shun away from the profession.

“I think the city understands the needs that we have, it’s just a question of funding,” Jones adds.

“Not just here but everywhere, I would like to humanize the officers. It’s important to make eye contact and say hello to help them feel comfortable and let them know that we are people, too.

Terry Key, an Edgehill resident, says he has learned to trust the police at the Midtown Hills precinct even though he grew up in a similar neighborhood where fear and skepticism of the police was a major factor. He also decided that it was up to him to help the neighborhood improve and reduce crime.

Rather than see kids and families struggle with boredom, mistrust and fear, Key decided to start a non-profit, the Edgehill Bike Club, that often works in tandem with the precinct at neighborhood events.

Edgehill Bike Club engages dozens of children and teenagers of all races in bike repair, neighborhood field trips, parties and get-togethers.

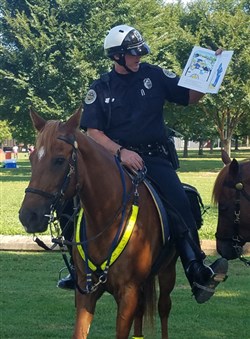

Oficer Nathan Clark, atop Skipper, reads “Officer Buckle and Gloria” to children during an East Nashville Hope Exchange reading event at Warner Elementary School this summer.

-- Photo Courtesy Of Metro Nashville Police Horse Patrol“I see myself in these kids, and I know how important it is for them to stay busy and see something positive in order to stay out of gangs and away from drugs. We need to work with the police as neighbors not enemies, and we’re getting a great start at that.”

Kristin Mumford, public information officer with MNPD, says Metro officers are fanning out in the community in large numbers and making a concerted effort to communicate with each other throughout various departments and divisions.

“MNPD supported 648 neighborhood and business groups and attended a total of 2,265 community meetings last year across Davidson County, an average of 6.2 meetings a day, every day of the year,” Mumford recounts.

“Commanders are plugged into their communities and have a weekly compstat meeting to determine where calls for service (victims/witnesses of a crime call for help, reports of suspicious activity, calls to crime stoppers or other citizen tips, etc.) is occurring and assign resources accordingly.”

“Community coordinator sergeants [like Sgt. Michelle Jones] attend community meetings, receiving direct input from neighbors,” Mumford notes, adding that each precinct employs a community coordinator sergeant. In addition to the weekly compstat meetings at the precinct level, the department commanders meet every Friday morning at the North Precinct, along with the other divisions.

Community Oversight - yes or no?

Even grassroots activists’ organizations that are pushing for changes at MNPD say the department is effective and appreciated in many areas, although they are pressing for changes nonetheless.

“We know that some (in MNPD) are working hard and addressing problems,” says Jane Boram, a member of Nashville Organized for Action and Hope, a grassroots coalition of 10,000 Nashvillians made up of over two dozen churches, non-profits, neighborhood associations and a few labor groups. “NOAH’s concerns are about systemic issues within the department that we feel are often hiding under the surface.”

NOAH is one of the several groups pushing for a police community oversight board in Nashville. Other groups include Black Lives Matter, the NAACP, Gideon’s Army, a grassroots organization aimed at improving opportunities for children, and Nashville Democracy, a local social justice group.

COB’s give civilians a role in reviewing police conduct and are used in over 100 American cities. Supporters say such a board would provide more accountability for law enforcement professionals in Nashville, make neighborhoods safer and improve the experiences and ultimate results for residents.

Civilian oversight is a popular issue for criminal justice reform advocates all over the nation. Nashville’s current efforts for particular reform began after the fatal police shooting of Jocques Clemmons by an officer in February 2017.

A bill to establish an oversight board in Nashville was drafted and sponsored by former Metro Councilman Sam Coleman earlier this year, but Mayor Barry and MNPD were strongly opposed, saying that Nashville’s current structure is working and citing skepticism about the effectiveness of COB’s.

The bill never happened and Coleman left the Council for a seat on the General Sessions bench in May.

“If you talk to people, even officers, they will admit that there are some long-standing problems [at MNPD],” says Seaku Franklin, a professor at Middle Tennessee University and adamant supporter of a COB in Nashville.

“Nashville struggles with progressive innovation more than it wants to admit, and it can be difficult to introduce reforms.”

Franklin describes a COB as “moderate step” in addressing various problems within the police department system that may have been swept under the rug – from the way officers respond to neighborhoods to mental health and stress-related issues within the force.

Despite his desire to add a layer of transparency to MNPD, Franklin doesn’t think Nashville has conditions that would lead to a police crisis on the level of Ferguson, Missouri.

“I would not describe the situation in Nashville as a powder keg, but one in which too many people have a deep sense of apathy and disillusionment.”

Despite the initial negative reaction to COBs by Mayor Barry and MNPD Police Chief Steve Anderson, Franklin says his group isn’t giving up.

They are in the process of working with individual Metro Council members and plan to reintroduce the legislation at some point in the future.

“This is not a radical solution,” he points out. “Community Oversight Boards are a respected tool and can be very effective at creating a healthier system and trust in the larger community.

“Some work better than others, but it’s unfortunate to dismiss them altogether as ineffective. They offer a common-sense approach.”