VOL. 41 | NO. 37 | Friday, September 15, 2017

Joy, lament mark impending closure of International Market

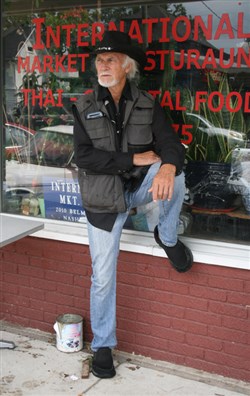

Chris Gantry waits outside International Market for the rain to let up so he can cross the street to his nearby apartment. The bulldozing of International Market -- his dining room for years -- is a good thing for the owner, he says. But for him and others it’s simply one more Music City landmark that will disappear.

-- Tim Ghianni | The LedgerRoosting at the International Market on Belmont Boulevard, Chris Gantry laments that this landmark restaurant across the street from his apartment is one more signal that his beloved “NashLantis” – a mystical city that drew wild-eyed artists like him 50 years ago – soon will disappear.

“Chris … He’s like family. He fuss at me. I fuss at him,” says Patti Myint, 73, who opened International Market & Restaurant 43 years ago, primarily out of a desire for some good Thai food. She still loves her restaurant and clientele but acknowledges the slow death – she’ll be open two more years before bulldozers roll in here – “is about time.”

Legendary singer-songwriter Gantry knows that the restaurant and market is a mere vestige of the city he “met” a half-century ago, when Christopher Cedzich – son of a New York-based piano prodigy Wladislaw Cedzich and his wife Alva Loussel Cedzich –moved here, already smitten by the town he imagined when listening to country music at the family home in Jamaica, Queens, New York City. He enjoyed the Big Apple radio concoctions of Sinatra, Satchmo, Bennett, Bing and Basie fine. But he wanted country music.

Of course, the “Cedzich” had to go if he was going to make it in a world presided over by folks with names like Cash, Monroe, Scruggs, Flatt, Jones, Miller, Cline and Nelson.

“When I got to the South, they couldn’t pronounce my name, and I had just recently seen the Burt Lancaster movie ‘Elmer Gantry.’” Christopher Cedzich liked the “easy-to-pronounce” last name of the title character and adopted it as his own.

The former Mr. Cedzich, now 75, is a little bit soft-voiced today, perhaps from too much tequila the day before, he admits.

But his full vocal range breaks through when he talks about NashLantis, the dream and memory he’s held onto for so long after being drawn by the same promise-for-creativity magic that lured the pilgrims listed above and others who followed.

Guys who became his friends, guys like Kristofferson, Billy Swan, Funky Donnie Fritts and Cowboy Jack. Hell, 50 years ago, even Bob Dylan – who like Gantry had found a more-marketable last name than the Zimmerman he received at birth – hung around here for a while.

“NashLantis means a place where musicians and artists were free to express themselves in the way they wanted to,” Chris says. “It is not being told how to do it, where to do it, who to do it with. Explored artistic vision: NashLantis offered that up.”

He’s been preaching in wistful rather than bitter terms about how Music Row – an easy stroll from International Market, where he has dined regularly for more than four decades – has changed.

“Somewhere the original aura and essence of that freedom slowly sank to the bottom of the ocean of mediocrity,” he proclaims. NashLantis, like the mythical Atlantis, disappeared beneath those waves.

“The reason I loved country music was because it was intrinsically enmeshed with the landscape of the people who wrote that music. You felt transported to that cabin. Transported to those smells. The Bible-reading mother. The drunkenness of the father.”

Oh, he knows that era is gone. And he can’t see it returning. “Now, the music is over-produced. It’s a landscape that is vacuous and has no substance to it.

“That is not right. That is not the heritage of this f------ music that founded this city.”

This is one of many encounters I’ve had with Chris, most at International Market, which is as much a home to him as is his apartment across the street.

“It’s kind of my dining room. I do business here. I carry on relationships here. I eat here. I watch CNN here,” is how he describes it to me after it was announced that International Market (and adjoining property) is going to be demolished to make way for expansion of Belmont University.

“I go in four times a week, at least,” he says. “Five. I’m kinda like the mayor of this street. I’ve been here 50-something years and I’ve never lived outside the Belmont area. Ever. Even when I first came (from New York City), I came to this street.”

And he explains his affinity for the area in blunt terms.

“For me, I’ve never had successful marital relationships, so my attachment to the hood is, like, what I know. I’m like a dog, I hang out where I grew up. I grew up as an artist right here.”

And this guy with his beloved late Chihuahua dog Tito’s portrait, name and the words “Be Happy” tattooed below his left shoulder, regrets that his dining room, the neighborhood gathering spot for 43 years is in its final throes.

Like Cash and June, like Hank, like Lester, Lefty, ET, Tater and Minnie Pearl, this neighborhood jewel will be gone. It will spend two more years on “Death Row” before destruction, aka “progress,” roll in.

Patti sits in a quiet part of her restaurant and market where she describes the kindness of the Belmont University president and details the desire, the hunger that fueled the founding of International Market all those years ago.

“I am from Thailand,” explains this sprightly woman. “I came to Nashville as a student. Graduated Trevecca 1972. Business. I was working on my graduate degree at MTSU.”

That’s when Patti, met and fell in love with a young man from Burma, “a TSU professor in math and engineering department,” she says.

She married Win Myint 43 years ago. (FYI: That last name is “pronounced ‘Mint’ like peppermint,” she explains.)

“When we got married, my husband had a house on Belmont,” she says, adding that her future and that of this building were quickly determined by her appetite.

“There was no Thai restaurant,” she recalls. “There was no food for me to eat.”

The idea to open a Thai restaurant in Music City was born thanks to regular constitutionals with her husband.

Chris Gantry and International Market owner Patti Myint both say the regulars here -- including the legendary singer-songwriter -- are “family.”

-- Tim Ghianni | The Ledger“We walked a lot on Belmont in the evening. This building was all boarded up. It had been an H.G. Hill’s store.”

She and her husband kept looking at the long, lonesome building – “It’s at least 75 years old,” she adds, scanning her restaurant and market.

During those strolls along broad Belmont Boulevard sidewalks, the idea was born to open a place where she could get the food she loved and also provide it to honky-tonk heroes, college professors, the everyday housewife and, maybe Cowboy Jack, as well as the multitude of students in this part of town.

Belmont University, which she says purchased her property for $6.5 million and allowed her two years to slowly close, is up the street, as well as over the hill. Nearby Vanderbilt and Lipscomb universities also are well-represented by the students who flock to this “hip” part of town for high-priced caffeine and used clothing.

“Property here used to be $20,000. Now it goes in the millions,” she says, looking out the front window to some of the newer, gentrification-funded neighbors.

“We walked by here, and I opened a little food restaurant and sell things, too,” she adds, pointing toward the shelves which offer up goods and groceries from Asia.

“It took about a year for people to know about it,” she remembers. “I made $44 the first day. At least I had food to eat. And my husband, the professor, was taking care of me.”

Customers may have been slow to discover this spicy and homey joint, but It didn’t take long for the neighborhood’s honky-tonk dreamer to find it, Chris says.

“When it was opened in the middle ’70s, it was like being in another country,” he acknowledges. “Back then a little Thai restaurant was weird.

“All you had in Nashville were the restaurants like Ireland’s and Varallo’s. When you find a foreign restaurant here it was big doings.”

He compares this building with so many of the architectural Nashville landmarks – particularly along Music Row, which he reckons is too late to save from corporate emasculation – that have gone away.

This writer, for example, frequented the Row in the early years of Chris’ half-century here, at a time when the outlaw movement was nurtured around song swaps, all-night beer binges, guitar picking, pills and pinball fests at my good friend Bobby Bare’s offices. (It should be noted that Bare wasn’t abusing his body like his friends were. He was napping or going home to get sleep at night. “Bare Disease” was outlaw “code” for a good night’s rest.)

I used to hang out, back then, at The Tally Ho Tavern, with its beer inside and pickers on the picnic tables out back. That bar – where then-undiscovered Kristofferson sometimes filled up and served up mugs of beer – became The Country Corner, where the atmosphere was virtually the same.

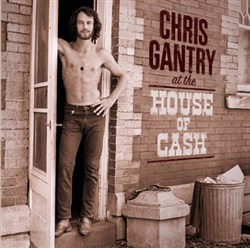

“Chris Gantry, who has written countless songs, is perhaps best known for his “Dreams of the Everyday Housewife,” a monster hit for the late Glen Campbell. His 1972 recording, “At the House of Cash,” releases on November 17 after being discovered by John Carter Cash.

Across the street, Gantry says, were Merle Kilgore and Audrey Williams’ Executive Club and Wally’s Professional Club, “secret” places where cowboys and cowgirls gathered – like so many Elks around the lodge bar – for quiet sips of liquor, for awhile avoiding blue laws, later just for time away from the fans and fame, Chris says.

The old Tally Ho, as well as those private clubs, were knocked down years ago to make way for offices of Curb and other record labels.

Chris doesn’t criticize Patti for taking the money for International Market.

“It will do so much good for her and her family,” he says. “But it is a symbol of a culture that has faded.

“That culture is what drew me to Nashville,” Chris says, adding that other representatives of that culture have long been “decimated” along Music Row.

Echoes of that culture, it should be noted here, soon will be released in a collection titled “Chris Gantry at The House of Cash.”

“I was writing for John Cash,” Chris recalls. “I had signed to his record label. I did a song called ‘Allegheny,’ and he signed me for a publishing deal.

“I told John I’d love to make a record.”

Cash turned over the keys to the House of Cash, and Chris recorded his new and somewhat skewed vision of the so-called “Nashville Sound.”

“I used synthesizers and had a string section. I used Brother Oswald on jug, Bobby Thompson doing banjo, Buddy Spicher playing fiddle,” he says.

“It was extremely over-the-top. It was like my Sgt. Pepper’s,” he adds, noting that when Cash listened to it he told Chris that it may not even find an audience “among the druggies.”

The 1972 tape was stashed away, like so many treasures, at the House of Cash.

Chris forgot about it. Cash died in 2003. Chris went on to other songwriting and performing ventures – he still can be seen regularly at Bobby’s Idle Hour, a guy named Lizard’s legendary “dive” that truly is almost a museum-like relic of what used to make up Music Row.

“It’s bleak. It’s sad,” Chris notes of that musical strip where condos and other high-rise buildings are erasing “the culture.”

The “At the House of Cash” recording emerged from the mists of time when it was discovered by the only child of John and June Carter Cash.

“John Carter found it and sent it to me.”

When his “At the House of Cash” album is released in November it will be something of a “Little Engine That Could” victory for this man who was drawn to Nashville by its freedom, its culture, its artistic “I Think I Can” attitude.

“It reflects me being at the top of my artistic game at the time and wanting to do what everybody else was doing back then: Something revolutionary.” Chris points out.

“It came out of my heart and my head. … If it hadn’t been for Johnny Cash, I never would have been able to do that,” he says. “My personality will not give up on being unique. … I will go to any length to rebel against anybody who tries to fit me into a mold that does not fit my spirit. I will not bend to other people’s version of mediocrity. …. These guys think I’m a bad guy for putting this shit down.

“Nobody gives a rat’s ass about me. Nobody cares. It’s almost like being on another planet,” he says of his relationship with the music industry.

Chris says International’s closing signals the loss of one more toehold of Nashville’s unique culture, the dream that lured him here.

Myint describes the restaurant closing in less-nuanced terms: “Patti is getting old. My husband has Parkinson’s. I want to rest and be with my family.”

“It’s not going to close for two years,” Chris explains. “She wants to tie up the loose ends.

“It’s time to close,” he says. “I think it’s a good idea. Tradition means nothing to Nashville now. It’s silly to keep a restaurant open in the name of tradition when it’s only going to get bulldozed over.”

Chris says it’s likely he won’t be around for the mortal dance of the wrecking ball.

“I may not be alive,” he admits. “Or I may go to the ocean, man, Puerto Rico. Maybe a little place in Cuba. Costa Rica. It doesn’t matter, as long as it’s by the ocean.”

He looks at this writer, sitting across from him at one of International Market’s dining tables.

He smiles and nods toward me. “We’re in the rearview mirror, man.”